Article

citation information:

Olszańska, S., Prokopiuk, I. Balanced scorecard as an

effective method for process management in a transport company. Scientific Journal of Silesian University of

Technology. Series Transport. 2021, 111,

119-128. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2021.111.10.

Sylwia

OLSZAŃSKA[1],

Iryna PROKOPIUK[2]

BALANCED

SCORECARD AS AN EFFECTIVE METHOD FOR PROCESS MANAGEMENT IN A TRANSPORT COMPANY

Summary. The strategic scorecard represents a major element of an

enterprise's management system, which contributes to improving the key areas of

operation, as well as precisely defining operational goals, metrics and tasks

within the strategical framework. Increasing competitiveness, as well as

progressive globalisation of the Transport, Shipping and Logistics (TSL)

services market, requires constant adaptation to change from managers. It is,

therefore, appropriate to use the strategic scorecard as it can be applied for

continuous monitoring of progress in the implementation of strategy and, if

necessary, for enhancing actions and the measurement system. The authors

analysed a transport company operating in the Podkarpackie Voivodship, with the

implementation of the strategic scorecard. The purpose of this article was to

create a strategic scorecard for the transport company in the context of

streamlining transport processes, while simultaneously improving the quality of

customer service, translating into maximising financial results.

Keywords: balanced scorecard, process management, transport company

1. INTRODUCTION

Currently, the transport market is

developing very dynamically. Companies from the TSL industry are offering a

variety of services to meet the increasing demands of their customers

[4, 5, 10, 11, 18]. In light of this, in an era of such strong competition,

transport companies must constantly improve their strategy in the context of

their processes [2, 6, 16]. Thus, strategic management is a key element of

management in transport companies [9, 12, 13]. In this aspect, the authors

believe that the use of a strategic scorecard provides major opportunities to

link these metrics with the improvement of the accepted strategy [1, 8, 17].

Moreover, the balanced scorecard includes a wide variety of goals and sensitive

metrics that permit a better understanding of the functioning of the enterprise

[7]. In addition, it combines

traditional informative indicators about the current implementation of

processes, with metres that analyse these processes, as well as factors that

contribute to shaping future results [3, 14]. Consequently, the use of a

properly executed balanced scorecard affects the improvement of transport

processes [15].

2. STRATEGIC SCORECARD AS AN ESSENTIAL ELEMENT SUPPORTING MANAGEMENT IN A TRANSPORT COMPANY

The use of a strategic scorecard

carries numerous benefits, for example, it helps to transform the company's

vision and mission into a strategy and to assign strategic goals to specific

metrics and tasks. The balanced scorecard focuses on perspectives that include

the key range of activities within the framework of process management.

Moreover, this management tool combines traditional (financial) indicators that

reflect past events in the company with metrics that analyse processes and

factors (for example, innovations), which shape the future in terms of

processes. An important advantage of introducing the balanced scorecard to the

enterprise process management system is its ability to monitor the

implementation of strategic goals daily , and consequently, improve them.

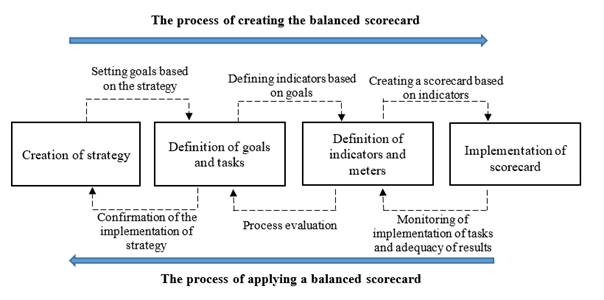

Furthermore, a strategic scorecard

enables the combination of planning and target setting

with initiatives to increase the efficiency of transport processes, and as a

result, build management feedback (Figure 1).

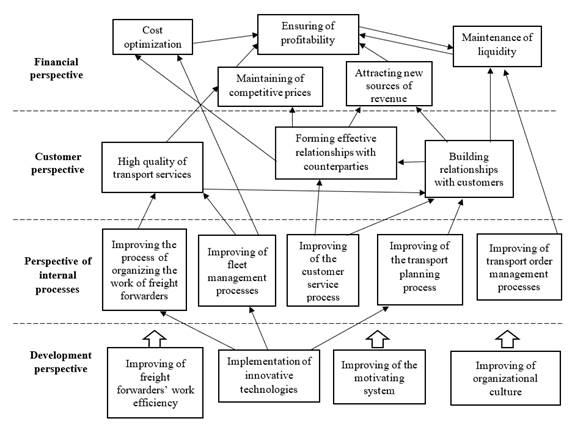

The strategic scorecard focuses on

four areas in the company, the perspectives. The strategy map, which focuses on

the causal link between the objectives and the measurers in the given

perspectives (Figure 2), is therefore relevant in this respect.

3. CHARASTERISTICS OF THE ANALYSED COMPANY

The analysed freight forwarding and transport

company is located in Rzeszów (Podkarpackie Voivodeship) and has been

operating since 2015. At the beginning of its activity, the company provided

only freight transport services, however, the scope of services expanded over

time with its forwarding, as part of which contracts were signed with

manufacturers in the chemical industry. The company provides services based on

cooperation with permanent contractors. It disposed of a transport fleet that

includes 6 transport sets of 3.5 t, 7 trucks of 12 t, 4 semi-trailers of 13.6

t, known as MEGA. In addition, with the growth of the company and increased

demand for services, there emerged a need for investment in the form of

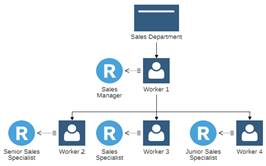

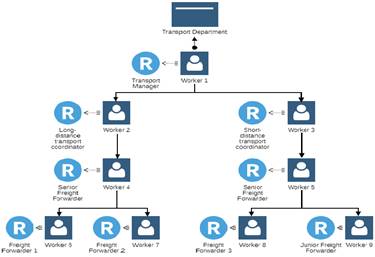

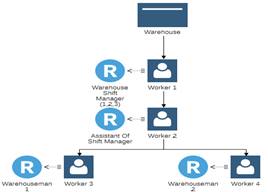

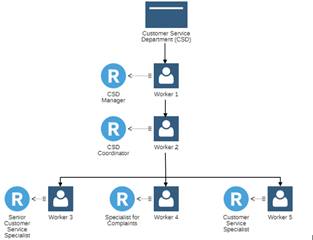

warehouse construction. Accordingly, the organisational structure of the

analysed company is as follows (Figure 3).

Fig. 1. Implementation and application of the scorecard in the enterprise

[authors’ study]

Fig. 2. Strategy map for the transport

company [authors’ study]

Fig. 3. Organisational structure at different

departments of the studied

freight forwarding company (R – denotes role) [authors’ study using

Adonis]

An integral element in the

implementation of processes in the enterprise are costs, therefore, the leading

objective in this respect is to generate maximum profit at minimal costs.

Consequently, both management, operational and functional processes are

fundamental to the company. In the case of the analysed enterprise, the process

of accepting orders from the customer, the process of planning and implementing

deliveries, and the process of accepting and issuing goods from the warehouse

were considered.

4. ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSPORT COMPANY IN TERMS OF THE STRATEGIC SCORECARD

The strategic scorecard is an

essential element of management in transport companies. It allows changing the

strategy into specific tasks and measures for their implementation. The

strategic scorecard draws particular attention to such areas as customer

service, process improvement, internal processes and finance, which are to

improve the situation in these four areas, either directly or indirectly, and

to generate the greatest possible profits and high market value.

To describe specific goals, we used

abbreviations, in which the first letter denotes the unit to which the goal

relates (K – general management, D – department), the second letter

is an abbreviation of the name of the perspective (K – client, f –

finance), and the third symbol is an ordinal number, for example, KK1 is a

target for the top management in the client's perspective.

The first perspective in the

strategic scorecard is the financial perspective. The key area of the company's

strategic goals is the financial indicators that make up the company's success.

The financial perspective mainly includes profitability in terms of profit and

expenses (Table 1).

Tab. 1.

The financial perspective of the strategic

scorecard for

top management in the analysed company

|

Goal |

Metres |

Value of metres |

|

Increase of service revenue (KF1) |

ROS

(return on sales) |

>0 |

|

Increase of asset profitability (KF2) |

ROA (return on assets) |

>0 |

|

Increase of equity profitability (KF3) |

ROE (return on equity) |

>0 |

|

Increase of enterprise productivity (KF4) |

ROI (return on investment) |

>0 |

|

Cost advantage in the industry (KF5) |

Average cost per kilometre in comparison to competitors |

PLN 2.90/km or 10% less than other companies |

In the context of this perspective,

the aim is to increase sales of services to the level of the ROS. Therefore,

all action must be geared towards a high value of the ROS, which will

consequently constitute a competitive advantage.

Another area of activity is the customer service perspective (Table 2). The organisation’s strategic goals from the perspective of the client include increasing the market share of services and improving customer satisfaction with the quality of the provided transport services.

Tab. 2.

Customer perspective strategic scorecard for

top management

|

Goal |

Metres |

Value of metres |

|

Increasing the transport market share (KK1) |

% of the sales of transport services in relation to sales in the segment |

min. 20% |

|

Improving customer loyalty (KK2) |

Number of regular customers increase in the number of customers number of new customers average value of transport orders |

50 35% 20 per month 1600 € |

|

Increasing customer satisfaction (KK3) |

Degree of customer satisfaction share of long-term contracts repeatability of transactions with 1 customer number of complaints |

min. 98% 40% min. 3 per week 0 |

|

Ensuring timely delivery of services (KK4) |

Percentage of orders executed on time |

99% |

|

Improving the company's image (KK5) |

Place in the ranking of the best companies according to customers |

1-5 |

Accordingly, each goal and measure

must be transformed into specific tasks to facilitate the implementation of the

strategy, for example, the company seeks to increase its market share in the

target market (KK1). The position of the company in the market is an important

indicator through which the company can observe its percentage of sales of

transport services with other businesses. Following such an assessment,

managers have the opportunity to take action towards improving the offered

services. Subsequently, the company will maintain its well-established

position, and since the goal of the senior managers is to gain customer loyalty

(KK2), then by taking such actions, the company can even achieve the position

of leadership in the competitive transport market. Hence, in this context,

customer satisfaction (KK3) is the main determinant; customer satisfaction

determines the success of the company. For this reason, it is quite important

to provide transport services in just-in-time and door-to-door systems, as well

as ensure continuous analysis of services, and consequently, their improvement

to meet the highest standards (kk4). Such actions will translate into another

equally important element, namely, the company's image (kk5), upon which the

company can expand the range of services, and thus, maximise the financial

result. The key strategic goal for the analysed enterprise is cost

optimisation. In this aspect, the company seeks to reduce operating costs

(Table 3), which will be measured by the percentage of the load capacity of

each type of vehicle. For large semi-trailers, this is 33-34 euro pallets

(dimensions 80 cm*120 cm), for a solo vehicle – 14-20 pallets, and a bus

8-10 pallets. Therefore, it is the task of the forwarding department to plan

transport routes in such a way as to convey as many goods as possible at the

lowest possible cost. Furthermore, the forwarding department should aim for a

vehicle fill rate of at least 96%.

Tab. 3.

Financial perspective of the balanced scorecard

for the forwarding department

|

Goal |

Metres |

Value of metres |

|

Reduction of operating costs (DF1) |

Filling of cargo space: semi-trailer, solo vehicles, buses up to 3.5 t |

96% 96% 100% |

|

Efficient cost management (DF2) |

Supercharging in the unloading area |

30 per month |

High-quality transport services is a

priority for the analysed company (Table 4). Thus, in the given perspective,

the forwarding department is driven by a single goal - timeliness (Fig. 4).

Tab. 4.

The customers’ perspective of the

balanced scorecard for the forwarding department

|

Goal |

Metres |

Value of metres |

|

Ensuring the punctuality of services (DK1) |

Punctuality of departure from the place of loading, timeliness of arrival at the place of unloading, timeliness of transshipment (if applicable) number of delays, % ETA 2h (estimated time of arrival) |

98% 98% 100% 1 per quarter 70% |

|

Providing customer access to information (DK2) |

Current order status update |

hourly |

The first step in the process of

cargo movement is loading onto the vehicle. The task of the transport

department, together with the warehouse and the driver, is to cooperate

efficiently to meet the deadline (DK1). The analysed company uses the ETA to

provide high-quality services. If the customer is very time-sensitive, the

company offers express or critical transport, which means that the cargo will

be delivered in the shortest possible time. The ETA indicator gives the

customer information about the time of delivery. Towards improving the quality

of service, the top management set an ETA target of 2 hours (that is, the

estimated delivery time may differ from the actual time by a maximum of 2

hours) at 70%. This target applies not only to express shipments but also to

all other shipments, so the company must aim for at least 7 out of 10 to be

delivered to the destination within ≈2 hours of the ETA. Although the

company strives to ensure that all deliveries are carried out timely, however,

in practice, considering unexpected events, delays may occur. The actions of

all functional cells responsible for transport are aimed at eliminating such

issues, and the maximum number of deliveries carried out after the deadline is

1 delivery in 3 months. In terms of high-quality customer service, an equally

important question in the transport department is keeping the customer informed

of the order execution status (DK2).

Fig. 4. Timeliness of deliveries at the

analysed enterprise

The profit of a company offering

services is largely based on the sum of margins on each transaction. To

maximise profit, the analysed company generates the desired margin of 10-20% of

sales (DsF1) (Table 5).

Tab. 5.

Financial perspective of balanced scorecard in

the analysed enterprise

|

Goal |

Metres |

Value of metres |

|

Profit maximisation (DsF1) |

Margin per transaction |

10-20% |

|

Increase in sale revenue (DsF2) |

Amount of sales of transport services |

PLN 50,000 per month |

In addition, the company applies a

preferential pricing policy for regular customers. When the margin is, for

example, 10%, it is applied to new customers to encourage further cooperation.

Another margin value will be determined in the case of express transportation

when the customer is keen on the fast delivery of cargo, and our company, as

one of the few in the region, can offer such a service. Another major goal for

the company is to increase the sale of transport services. Therefore, the

managers strive to ensure that each employee of a given department receives

orders for at least PLN 50,000 every month; according to the financial plan,

exactly such an amount will be optimal for covering the costs of the company's

activities and ensuring financial liquidity. Approximately 50% of the revenue

is to come from the delivery of services to regular customers who, for example,

will have to transport 24-30 tonnes of goods two or three times a week. On the

other hand, around 5-10% of revenue can originate from the orders of customers

who will use the company’s services not less than once a month. The

remaining 40-45% of revenue should be the result of effective negotiations of

freight forwarders with new customers.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The

strategic scorecard is an extremely important element of effective management

in transport companies. It is a tool for implementing the adopted strategy

since it allows determining both specific metrics of strategic goals and a list

of tasks, the implementation of which will allow achieving the desired results

in line with the company's strategy. In this article, the authors developed a

strategic scorecard for the studied company to accurately determine the desired

values, including those from the client's perspective, through which managers

can determine whether the adopted strategy is appropriate or requires

improvement. Subsequently,

the presented scorecard has contributed to the identification of vulnerable

areas in the analysed enterprise. Thus, by taking immediate action, the

company's processes were streamlined, leading to the expansion of activities on

the European market through cooperation with new counterparties. Consequently,

the inclusion of the tool presented in this article in the activities of the

analysed enterprise will ensure success in the long term.

References

1.

Emerling I. 2018. „Balanced scorecard and its role company

management”. Research papers of

Wrocław University of Economics 514: 108-115. ISSN: 1899-3192. DOI: 10.15611/pn.2018.514.10.

2.

Galkin A. 2019. „Mechanisms for increasing of transportation efficiency

using joint service of logistics systems”. Archives of Transport 49(1): 7-24. DOI: 10.5604/01.3001.0013.2770.

3.

Galkin A., V.

Skrypin, E. Kush, K. Vakulenko, V. Dolia. 2017. „Invest Approach to the Transportation Services Cost Formation”. Procedia Engineering 178: 435-442. DOI: 10.1016/j.proeng.2017.01.086.

4.

Naumov V., O.

Kholeva. 2017. „Studying Demand for Freight Forwarding Services in

Ukraine on the Base of Logistics Portals Data”. Procedia Engineering 187: 317-323. DOI:

10.1016/j.proeng.2017.04.381.

5.

Kuśmińska-Fijałkowska

A., Z. Łukasik, J. Kozyra. 2019. „Consolidation as a Key to Success an European Transport Enterprise Case

Study”. TransNav, the International Journal on Marine

Navigation and Safety of Sea Transportation 13: 889-894. DOI: 10.12716/ 1001.13.04.24.

6.

Kuśmińska-Fijałkowska

A., Z. Łukasik, J. Kozyra. 2017. „Noise Reduction in Railway Traffic as an element of Greening of

Transport”. In: Marine Navigation

and Safety of Sea Transportation. CRC Press. DOI: 10.1201/9781315099088-22.

7.

Zhou W., J. Zhang,

H. Chen. 2010. „Service quality evaluation for international freight

forwarder”. Proc. of the 7th Int. Conf. on Service Systems and Service Management. P. 515-519.

8.

Tavassoli M., G.R.

Faramarzi, R.F. Saen 2014. „A joint

measurement of efficiency and effectiveness using network data envelopment

analysis approach in the presence of shared input”. OPSEARCH 52(3): 1-15. DOI: 10.1007/s12597-014-0188-z.

9.

Kholeva O.G. 2017.

„Forming the strategies of sustainable development of

freight forwarders at transportation market”. Науковий

вісник НГУ 3: 129-134.

ISSN: 2071-2227.

10.

Dolia

V., Galkin А.

2013. „Results of

efficiency evaluation of investing alternative projects of transportation

customer service”. Technology Audit

and Production Reserves 5(3-13): 4-6. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.15587/2312-8372.2013.18458.

11.

Melovic

Boban, Slavica Mitrovic, Arton Djokaj, Nikolai Vatin. 2015. „Logistics

in the Function of Customer Service- Relevance for the Engineering

Management”. Procedia Engineering 117(1):

802-807. DOI: 10.1016/j.proeng.2015.08.255.

12.

Dong J.Q., Z.G. Huang,

L. Huang, Z.X. Wu, Y. Do, W. Hai-Ying. 2012. „Enhancing Transport Efficiency by

Hybrid Routing Strategy”. EPL (Europhysics Letters) 99(2):

1-10. DOI: 10.1209/0295-5075/99/20007.

13.

Zimon D., J. Tyan,

R. Sroufe. „Implementing

Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Reactive, Cooperative, and Dynamic Models”. Sustainability

11(24): 1-22. DOI: 10.3390/su11247227.

14.

Monghasemi S., M. Abdallah,

A. Tawfik, C. Clevenger. 2018. „Transportation Planning and Sustainability”. International Conference on Transportation and Development:

265-276. DOI: 10.1061/9780784481561.026.

15.

Ocalir-Akunal Ebru

Vesile. 2016. „Decision Support Systems in Transport Planning”. Procedia Engineering 161: 1119-1126. DOI: 10.1016/j.proeng.2016.08.518.

16.

Dusko Kalenatic,

Karol Viviana Moreno Valbuena, Luz Mancera, et al. 2011. „Methodology of logistics planning based on

project management and system dynamics for business service providers”. Revista Facultad

Deingeniera – Universidad de Antioquia 58: 208-218. ISSN: 0120-6230.

17.

Yi Li, Libin Lu. 2019. „Research on

B2C Reverse Logistics Service Quality Evaluation”. System, Proceedings of the 5th International

Conference on E-Business and Applications: 10-15. DOI: 10.1145/3317614.3317631.

18. Lysenko-Ryba Kateryna. 2017. „The Impact of Reverse Logistics on Customers

Satisfaction”. Przedsiębiorczość

i Zarządzanie XVIII(8): 137-146. ISSN: 2543-8190.

Received 28.01.2021; accepted in revised form 30.04.2021

![]()

Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License