Article

citation information:

Siqueira Silva, D., Csiszár, C., Földes,

D. Autonomous

vehicles and urban space management. Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2021, 110, 169-181. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2021.110.14.

Dahlen SIQUEIRA SILVA[1],

Csaba CSISZÁR[2], Dávid FÖLDES[3]

AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES AND

URBAN SPACE MANAGEMENT

Summary. Discussions on how

urban space would be transformed by the use of autonomous vehicles (AVs) are

scarce. This study identifies the impacts caused by the shared use of AVs on

urban parking and urban space management. An estimation method was

formulated considering the reduction in parking demand, the possible alteration

in vehicle ownership, and the reallocation of urban space. A case study was

performed in a 673,220 m2 area through

scenarios created by using real data of parking spaces and the results of

previous studies. Results showed that parking spaces can be saved with the use

of shared AVs, which would allow the reallocation of urban space to new uses

(for example, implementation of around 12,000 bike-sharing docking spots, 10 km

bike lanes, 7 km additional traffic lane or 140 ‘parklets’).

The results contribute to revealing the positive impacts of AVs.

Keywords: autonomous vehicle, urban space, land use,

shared mobility, reshaping cities

1.

INTRODUCTION

As autonomous

vehicles (AVs) are under development, analysis of their impacts has become

important for understanding how they would affect people and space management.

Existing studies [9,14,19-22] focused on formulating

models and calculating the reduction in the number of vehicles and parking

spaces. However, discussions on how urban space may be transformed were barely

made. Therefore, this research focuses on the transformation in urban space

generated by the use of AVs considering how changes in number, location and use

of parking spaces could save urban space and which new functions could be given

to them.

A method was

developed to estimate the reduction in demand for parking according to

alteration in ownership and the shared use of autonomous vehicles (SAV), as well as to estimate the new uses of the urban

space saved according to the priorities of decision makers. In this study, all

members of the society that are able to make decisions regarding future changes

in the city are considered decision makers. To demonstrate the applicability of

the method, a case study was performed in an area in Budapest, Hungary.

Different scenarios were created based on previous studies and real data of

parking spaces were applied.

This paper is

structured as follows: results of relevant literature are revealed in Section

2. The developed estimation method, the scenarios and the collected data are

presented in Section 3. The results and findings are discussed in Section

4. This paper is completed by concluding remarks including future research

directions.

2.

STATE OF THE ART

2.1.

Autonomous vehicles in a sharing system

A

car is parked approximately 95% of its lifetime [18]. The average car spends

about 80% of the time parked at home, is parked elsewhere for about 16% of the

time, and thus, only in movement for the remaining 4% [15Błąd! Nie można odnaleźć

źródła odwołania.]. The main

motivation to use private vehicles is work-related, which causes a high parking

demand in the daytime, having the overall average parking time of 3.5 hours [15,18]. Nowadays, drivers need to walk to the parking location

to pick up their vehicles. Furthermore, cruising for parking spot results in a

tremendous amount of excess driving causing air pollution, crashes and traffic

congestion [10,11,18,22]. Nevertheless, the access

walking distance and cruising for a parking space are not a problem for AV

users. There is no need to park the vehicle close to the destination. However,

reaching a distant and cheaper parking space can increase the empty runs and vehicle

miles travelled, generating additional cost, and consequently, the need for a

centralised parking management and control of AVs. Some modelling studies

carried in the United States [6,20] and Europe [1,2] show that the use of

private AVs increase vehicle miles travelled, reduce public transport use and

slow modal shift. Moreover, it leads to a more dispersed urban growth [16,17].

AVs

have the potential of becoming a major catalyst for urban transformation (for

example, changing urban infrastructure, city design, mobility habits, and time

spent during travelling) [5]. It is suggested that the use of SAV fleet could mitigate current issues, such as increasing

car ownership, traffic congestions and, subsequently, the time spent travelling

daily. To reach the benefits, the social acceptance of AVs is needed, however,

technophobia was found as a significant factor against AV use [12].

The

impacts of the three types of ownership and market acceptance scenarios that

may shape the future demand for parking are [13]:

·

Private use: the number of car parking might be

the same as today, however, changes in their location might occur as AVs can

park far away from the destination.

·

Shared use, but single occupancy: fewer parking

spaces are expected, the duration of parking would be reduced due to sharing.

·

Shared use with multiple occupancy: only a few

vehicles need to park, and the location of parking spots is in strategic

locations to provide mobility service with minimum waiting time.

Private

shared use can be also distinguished if the privately owned vehicle is shared

among acquaintances and family members. Moreover, AVs can park more efficiently

than humans, the on-street parking spaces might decrease independent of the

reduction in vehicle number. Furthermore, on-street parking might be exchanged

to off-street parking such as parking garages which could be automatised. Automatisation

optimises the available space for its construction as they do not need

facilities for human use. In addition, off-street parking may serve as points

for charging, cleaning, maintenance and waiting areas for SAVs.

Moreover, the multi-row layout could also reduce parking space. A relocation

strategy could be used to release barricaded vehicles. The extent of vehicle

relocation depends on the layout of the car park; square-shaped car parking

spaces can be more effective. The use of AVs can decrease the need for parking

space by an average of 62% and a maximum of 87% [7].

Main

finding of existing studies regarding the alteration of parking space caused by

the different ownership of AVs are summarised in Błąd! Nie można odnaleźć

źródła odwołania.. The detailed

results were used as inputs for the developed method presented in this paper.

Tab.

1

Studies about

reduction of parking spaces

|

Ownership |

Study |

Study area |

Characteristics |

Reduction in parking spaces |

|

Private Shared |

[20] |

Atlanta, USA |

SAVs among the members of the same household |

-9.5% number of

private vehicles, +15 minutes travel

time per trip, -12.3% parking space

|

|

Shared, single occupancy |

[18] |

Boston, USA |

33% or |

-16% or

-48% parking space |

|

[5] |

Atlanta, USA |

SAV, 5% market penetration level |

-90.3% and

-92.4% parking spaces; |

|

|

[9] |

Lisbon, Portugal |

100% or

50% SAVs |

-89.3% or -21.2% parking spaces |

|

|

Shared, multiple occupancy |

[14] |

Munich, Germany |

AV taxi fleet,

0%, 20% or 40% taxi |

40% penetration

rate, 1 AV taxi can replace 3 conventional cars |

|

[13] |

General |

2% of market penetration

level |

-90% parking spaces with ridesharing |

|

|

[9] |

Lisbon, Portugal |

100% or

50% SAVs |

-94.4% or -24.2% parking spaces |

Former

on-street parking areas could be divided into lanes for bicycles, other

micro-vehicles or public transportation services. Consequently, urban space

management may be renewed promoting walkability as well as areas focusing on

well-being.

2.2.

Pick-up and drop-off areas

One

of the most important aspects considered in designing the urban space for AVs

is the pick-up and drop-off areas, especially in the case of shared use.

Designated space is needed to eliminate conflicts with the surrounding roadways

and parking spaces.

The

aspects to be considered when designing drop-off and pick-up areas are

location, style, sign, connection and comfort.

·

The location of these areas should be

close to the entrance of buildings, allowing users to quickly get in or get

off. Separated pick-up and drop-off areas are preferable so as to reduce

conflict areas and a better flow of users, however, common pick-up/drop-off

area could be built if the space is limited.

·

The style of the areas should represent

the functionality to distinguish it from other infrastructure elements.

·

The areas should have signs indicating

their delimitations to support travellers and avoid misuse of it.

·

Seamless connection should be designed between

pick-up and drop-off areas to allow AVs to quickly pick another passenger after

dropping-off the previous one.

·

A high level of comfort is needed during

the waiting time (benches, phone charging, lighting, internet, etc). However, the waiting time can be minimised with

efficient demand-capacity coordination.

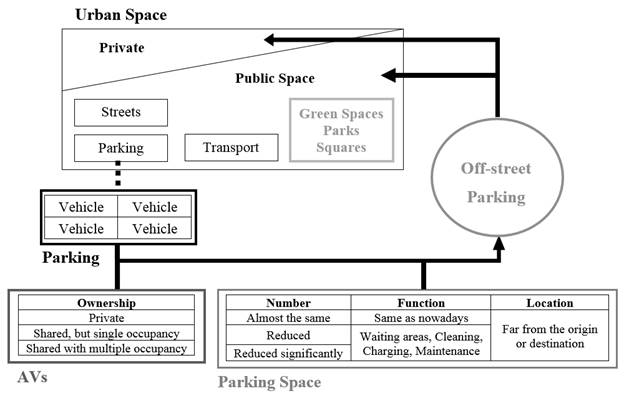

Concluding

the results of the state of the art, the alteration in parking management as

the consequence of AVs is presented in Błąd! Nie można odnaleźć

źródła odwołania.. Urban space

is composed of private space and public space, such as streets, parking areas,

green spaces, parks, and squares. After the introduction of AVs, especially SAVs, the use of urban public space will be altered. The

most important impacts are fewer parking spots, off-street parking facilities

instead of on-street parking spaces, remote parking, parking close to each

other and reallocation of urban spaces.

3.

METHODOLOGY

3.1.

Estimation method for urban space transformation

The

modal share, the type of ownership and parking could cause a significant

alteration in public parking space management, which could be transformed into

new uses according to the priorities of decision makers. However, the travellers’

willingness to walk to take an AV might influence how much of the saved parking

spaces would be transformed to pick-up and drop-off areas. To estimate the size

of the area allocated for new uses and to assume the type of the new uses (bike

lanes, green areas, etc.) after the adoption of SAV

fleet, a method was elaborated considering the aspects presented in Błąd! Nie można odnaleźć

źródła odwołania..

Fig. 1. Urban space in the future with

the use of AV

Fig. 2. Aspects considered creating new uses

for public space

The

annual alteration of urban space and future parking demands are considered due

to the expected increase in AV adoption. This method provides predictions

regarding changes in urban space management as a tool for city planners. The

result of this method is the future parking demand and possible reallocation of

urban space. As a limitation, alterations in population and the location of

households are not considered. Furthermore, alteration in loading points and

charging spots for electric vehicles are neglected. The used indexes are presented

in Tab. 2, the variables used

during the calculation are introduced in Tab. 3.

Tab.

2

Indexes

|

Sign |

Name |

Set

of value |

|

|

Parking

alignment |

k=1..z (1: parallel, 2: 45°,

3: 90°, etc.) |

|

|

Type

of ownership |

j=1..m (1: private, 2: private

shared, 3: shared with single occupancy, 4: shared with multiple occupancy,

etc.) |

|

|

Type

of new use |

x=1..y (1: public transportation,

2: improving walkability,3: bike-related

strategies, 4: additional traffic lane, etc.) |

Tab.

3

Variables

|

Sign |

Description |

|

|

Rate of increase in the number of conventional

vehicles in year t |

|

|

Number of conventional vehicles in the year t-1

according to j ownership |

|

|

Rate of increase in the number of AVs in the

year t according to j ownership |

|

|

Number of AVs in the year t-1 according

to j ownership |

|

|

Percentage of saved parking space caused by

autonomous vehicles according to j ownership |

|

|

Percentage of off-street parking space from

the total parking spaces |

|

|

Percentage of parking spaces according to k

arrangement |

|

|

Area of each parking space according to k

arrangement [m2] |

|

|

Rate indicating how many private areas will be

created in year t |

|

|

Percentage of private area created in the

previous year (t-1) |

|

|

Rate indicating how much pick-up and/or

drop-off areas will be created in year t |

|

|

Percentage of pick-up and drop-off area

created in the previous year (t-1) |

|

|

Rate of space applied for new use related to x

new use |

|

|

Area for x new use correspondent to the

previous year (t-1) |

Step 1: Number of parking spaces according to demand

The demand for parking in year t (D(t))

is calculated according to (1).

|

|

(1) |

Step 2: Demand for a parking area

The necessary area for parking in year t (P(t))

[m2] is calculated according to

(2).

|

|

|

(2) |

Step 3: Percentage of saved spaces used for private areas and pick-up

and drop-off areas

Saved space is defined as the extra space resulting from the reduction

of parking demand caused by the use of SAV fleet. The

percentage of it (Dm(t)) decided to use for private areas or pick-up and drop-off areas by

decision makers is calculated in (3).

![]() (3)

(3)

Step

4: Area allocated for new uses

The size

of the area in the year t (N(t)) [m2] allocated for new

uses is calculated according to (4) or (5). The latter considers the combination of areas for new uses, such as an area for

cycling or for public transportation, as well as the rates of

increment/decrement of this portion of land considering decision makers’

priorities.

|

|

|

(4) |

|

|

|

(5) |

3.2.

Creation of scenarios

Creation

of scenarios represents an important tool to analyse how beneficial the

adoption of SAV fleet is for the reduction of parking

spaces. Five scenarios were created (Tab. 4) and their characteristics were

based on previous studies [9,13,20]. Scenarios

simulating the transitional period, when the whole vehicle fleet is not fully

composed by AVs, were created to analyse whether AV acceptance in this period

would bring significant benefits. It is important to notice that Scenario 4

(transitional) presents private AV fleet and, in Scenario 5 (mix), the fleet is

private but shared among members from the same household. It was assumed that

population and land use would remain the same, as well as reduction of parking

spaces in Scenarios 4 and 5, would happen proportionally to the results

obtained from Scenarios 1, 2 and 3 according to the type of ownership. For

instance, in Scenario 5, the private SAV fleet would

have 9.5% reduction in parking spaces according to the result in Scenario 1.

Tab. 4

Scenarios

assumed with the use of AVs

|

Scenario |

Condition |

Input Parameters |

|

1 |

Private ownership |

9.5% reduction in

private vehicles with private sharing. |

|

2 |

Shared, single |

89.3% reduction in

parking spaces with 100% shared fleet. |

|

3 |

Shared, multiple occupancy |

94.4% reduction

in parking spaces with 100% shared

fleet. |

|

4 |

Transitional |

AV private fleet:

27%, shared single occupancy fleet: 33%, shared multiple occupancy fleet:

40%. |

|

5 |

Mix |

Private SAV fleet: 10%, shared single occupancy fleet: 50%,

shared multiple occupancy fleet: 40% |

3.3.

Data Collection

The

following data should be collected according to the segments (for example,

sides of a block):

·

the number of parking spaces,

·

the location of parking spaces (for example,

both sides of the street),

·

arrangement of parking spaces (parallel, 45°

or 90°),

·

whether the parking space takes part of the

sidewalk and what the extension of the sidewalk occupancy is,

·

characteristics of

the surroundings.

The

values used for calculation about the occupied area of parking spaces are based

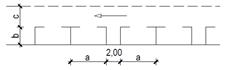

on the dimensions according to the type of parking space shown in Fig. 3.

|

|

|

|

|

a=5m, b=2.5m, c=3.5m; |

a=5.2m, b=2.5m, c=3.5m; |

a=5.5m, b=2.5m, c=5m |

Fig. 3. Dimensions of the parking

spaces according to the type

(Source: BME, Department of

Industrial and Agricultural

Building Design, 2013)

To

prove the applicability of the developed estimation method, it was applied to

an area in the district XI of Budapest, Hungary. It is mainly a residential

area, however, it includes a big shopping mall and a university as it is

delimited by important public transportation stations with underground and

several tram lines. Błąd! Nie można odnaleźć

źródła odwołania. illustrates

the delimitation of the studied area. The district is 33,490,000 m2 and had 148,517 inhabitants in January 2019

according to the National Statistical Office. The area of study has

approximately 673,220 m2 which would be

occupied by around 3,000 inhabitants considering a uniform distribution of

population on land. The data regarding parking spaces was collected on field.

The area was divided into 120 segments. Photos were taken to support the

analysis about how urban space is used.

University Shopping Mall

![]()

![]()

Fig. 4. Delimitation of the studied area (Source: Google Maps)

4.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1.

Situation analysis

In

the studied area, mainly on-street parking spaces have been created. This type

of parking was considered the easiest solution for managing the increasing

parking demand due to the limited number of garages as the buildings are old.

As the sidewalks presented large widths, parking was allowed on part of the

sidewalks in several cases. In some sidewalks, the entire vehicle is parked on

the sidewalk and, in others, part of the vehicle is on the sidewalk. Therefore,

sidewalks were shortened and space for pedestrians was reduced.

5%

of the total area, 32,016 m2, is used for

parking. Błąd! Nie można odnaleźć

źródła odwołania. shows the

number of parking spaces and the occupied territory according to type of

parking.

Tab. 5

Number of vehicles and area of parking

|

Type of parking space |

0° |

45° |

90° |

Total |

|

Number of parking space |

1,076 |

1,279 |

141 |

2,496 |

|

Area for parking [m2] |

13,450 |

16,627 |

1,939 |

32,016 |

Two

thousand five hundred parking vehicles were counted during the on field

measurement. As most of the parking spaces do not have delimitation painted on

the floor, excessive space between vehicles may occur. Moreover, additional

space needed for opening the doors will not be necessary with the use of AVs.

52%

of the original space of the sidewalk was taken, leaving small space for

pedestrians. In many situations, the space left is not enough for two people

walking side by side. 8% of sidewalks are narrower or equal to 1.20 m, the

smallest width is 0.9 m, which coincidently happens in the segment where

parking space takes around 85% of the sidewalk. Near popular points of interest

where the number of pedestrians is high, pedestrians must squeeze themselves to

commute. Furthermore, some drivers park their vehicles taking more space than

the delimited parking space, which reduces, even more, the available space for

pedestrians and brings irregularities, presenting danger mainly to the disabled

people [3,4,8].

4.2.

Application of the method

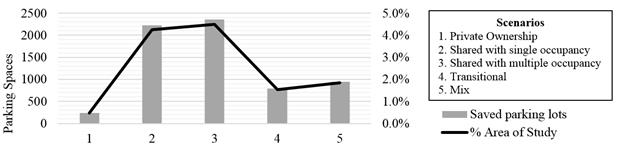

The

results considering the determined scenarios are presented in Błąd! Nie można odnaleźć

źródła odwołania.6.

Furthermore, Błąd! Nie można odnaleźć

źródła odwołania. illustrates

the result of multicriteria analysis relating the

saved space with the correspondent percentage of the area of study, which

allows better visualisation of the benefits. For calculating the saved space,

the elimination of parking spaces at 90 and 45° were the priority as more

space is occupied than the parking space with arrangement of 0°.

Tab.

6

Saved

space in the area of study with use of AVs

|

Scenario |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

Saved parking spaces |

238 |

2,229 |

2,357 |

791 |

948 |

|

Saved space [m2] |

3,200 |

29,083 |

30,747 |

10,389 |

12,430 |

|

Saved space [%] |

0.47 |

4.24 |

4.49 |

1.54 |

1.85 |

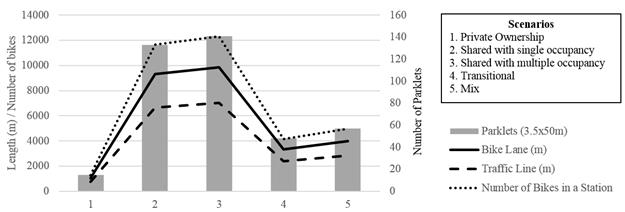

Decision

makers have an important question to answer regarding how saved space should be

used. Considering the ideal scenario for having a more liveable city, decision

makers should choose the use of a small percentage of the saved space for

building pick-up and drop-off areas, for example, 20%, and the rest for green

and open spaces. The possible new uses of the saved spaces are shown in Błąd! Nie można odnaleźć

źródła odwołania.. The deployment

of possible bike lanes, additional traffic lanes, parklets

and docking spots in bike-sharing systems instead of parking spaces were

examined. Parklets are defined as areas with benches

and green spaces implemented in areas previously allocated to parking spaces.

Their width has the same dimension as the previous parking space. The parklets were estimated with dimensions of 3.5x50 m, the width of bike lanes was assumed as 2.5 m to

benefit the two directions of bike traffic, the width of traffic lane was

assumed as 3.5 m and the space occupied per a docking spots was assumed as 1x2 m. During the calculation, the ambitious predictions of

the modal shift[4]

for 2030 in Budapest (walking: from 9 to 20%, cycling: from 2 to 10%) was

considered.

Fig. 5. Saved parking spaces and correspondent percentage according to

the determined scenarios

Fig. 6. New uses for the saved parking spaces. (Source:

Author)

Besides

the gained urban space, all of the saved space could be transformed into green

spaces. Additionally, sidewalk expansions could be done, and the estimated

length of the traffic lane may be provided for public transportation.

Furthermore,

a small number of on-street parking spaces could be left for shared use. These

spaces would be used by delivery companies, for loading and unloading, and by

electric vehicle users for charging. Smartphone applications for booking a

parking space may be very useful to improve the efficiency of the SAV service when planning stops for charging, cleaning

and/or maintenance as well as when waiting for a new user.

Finally,

the tendency of the presented results was expected. As there is an increase in

the number of shared vehicles, there is more possibility of reducing the number

of vehicles on the streets, and consequently, the demand for parking spaces.

However, different results are brought depending on the city to which the

method is applied as the needed parking spaces are influenced by the settlement

structure, trip durations and distance travelled.

5.

CONCLUSION

The

introduction of AVs affects urban space management. However, the caused impacts

have not been well known yet. Therefore, this study presented an estimation

method for urban space transformation as the main contribution, considering the

parking demand, the saved parking space and its reallocation.

It

was found that the more SAVs fleet are used, the more

savings in parking spaces are achieved which may receive new uses according to

decision makers’ priorities. Results showed that parking spaces can have

new uses, such as the implementation of around 12,000 bike-sharing docking

spots, 10 km bike lanes, 7 km additional traffic line or 140 ‘parklets’. The results presented practical

applicability because they can suggest the intensity of changes in urban space

management and serve as input in city planning.

The

method should be adapted to local characteristics as parking habits,

distribution and location of parking spaces may vary from one city to another.

Future

research could consider local characteristics relating to the acceptance of AVs

and the priorities of decision makers regarding the changes in urban space

through a questionnaire survey. Furthermore, changes in population and in the

location of households can be included.

Acknowledgement

The

research reported in this paper was supported by the Higher Education

Excellence Program in the frame of Artificial Intelligence research area of

Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BME FIKP-MI/FM).

EFOP-3.6.3-VEKOP-16-2017-00001:

Talent management in autonomous vehicle control technologies. The Project is

supported by the Hungarian Government and co-financed by the European Social

Fund.

References

1. Boesch P.M., F. Ciari, K.W. Axhausen. 2016. „Autonomous vehicle fleet sizes required to

serve different levels of demand”. Transportation Research Record 2542(1):

111-119. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3141/2542-13.

2. Correia G., D. Milakis, B. van Arem, R.

Hoogendoorn. 2015. “Vehicle automation and transport system performance”. In: Handbook on transport

and urban planning in the developed world, edited by M. Bliemer,

C. Mulley, C.J. Moutou. P.

498-516. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. ISBN: 978 1 78347 138 6.

3. Czech

Piotr. 2017. „Physically disabled pedestrians - road users in terms of

road accidents”. In: Lecture

Notes in Networks and Systems 2: 157-165.

DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-43985-3_14. Edited by: Macioszek E., Sierpinski G. Contemporary challenges of transport systems

and traffic engineering. 13th Scientific and Technical Conference on

Transport Systems. Theory and Practice (TSTP).

Katowice, SEP 19-21, 2016.

4. Czech

Piotr. 2017. „Underage pedestrian road users in terms of road

accidents”. In: Advances

in Intelligent Systems and Computing 505: 33-44. DOI:

10.1007/978-3-319-43991-4_4. Edited by: Sierpinski G.

Intelligent transport systems and travel behaviour. 13th Scientific and Technical Conference on

Transport Systems. Theory and Practice (TSTP).

Katowice, SEP 19-21, 2016.

5. Duarte F., C. Ratti.

2018. „The Impact of Autonomous Vehicles on Cities: A Review”. Journal of Urban

Technology

25(4): 3-18. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1080/10630732.2018.1493883.

6. Fagnant D., K.M. Kockelman, P. Bansal. 2015. „Operations of shared autonomous vehicle fleet

for Austin, Texas, market”. Transportation Research Record 2536: 98-106. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.3141/2536-12.

7. Heinrichs D. 2016. “Autonomous Driving and

Urban Land Use”. In: Autonomous Driving, edited by Maurer M., Gerdes J., Lenz B., Winner H. P. 213-231. Germany:

Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. ISBN: 978-3-662-48845-4.

8. Ignaccolo Matteo, Giuseppe Inturri, Nadia Giuffrida, Michela Le Pira, Vincenza Torrisi, Giovanni Calabrò. 2020. “A step towards walkable environments:

spatial analysis of pedestrian compatibility in an urban context”. European Transport \ Trasporti Europei 76 n. 6. ISSN: 1825-3997.

9. International Transport Forum. 2015. Urban

Mobility System Upgrade - How shared self-driving cars could change city traffic.

Paris: Corporate Partnership Board Report. Available at:

https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/docs/15cpb_self-drivingcars.pdf.

10. Jacyna M. 1998. “Some aspects of multicriteria

evaluation of traffic flow distribution in a multimodal transport

corridor”. Archives of Transport

10(1-2): 37-52.

11. Jacyna M., J. Merkisz. “Proecological

approach to modelling traffic organization in national transport system”.

Archives of Transport 2(30): 43-56.

12. Koul S., A. Eydgahi. 2020. ,,The Impact of Social Influence, Technophobia, and

Perceived Safety on Autonomous Vehicle Technology Adoption”. Periodica Polytechnica

Transportation Engineering 48(2): 133-142. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3311/PPtr.11332.

13. KPMG. „Parking demand in the

autonomous vehicle era”. Available at: https://home.kpmg/xx/en/home/insights/2017/07/parking-demand-in-the-autonomous-vehicle-era.html.

14. Llorca C., A.T. Moreno, R. Moeckel. 2017. „Effects of Shared Autonomous Vehicles on the Level of Service in the

Greater Munich Metropolitan Area”. International Conference on

Intelligent Transport Systems in Theory and Practice. Munich, Germany.

Available at: https://www.bgu.tum.de/fileadmin/w00blj/msm/publications/moeckel/2017_llorca_etal.pdf.

15. RAC Foundation. „Spaced Out -

Perspectives on parking policy”. Available at:

https://www.racfoundation.org/assets/rac_foundation/content/downloadables/

spaced_out-bates_leibling-jul12.pdf.

16. Schmidt Marie, Stefan Voss. 2017. „Advanced systems in public

transport”. Public Transport

9(1-2) Special Issue: 3-6.

17. Soteropoulos A., M. Berger, F. Ciari. 2019. „Impacts of automated vehicles on travel behaviour and land use: an

international review of modelling studies”. Transport Reviews

39(1): 29-49. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01441647.2018.1523253.

18. The High Cost of Free Parking by Donald Shoup.

Summarized by Tri-State Transportation Campaign. 350 W 31st Street, New York,

NY 10001 p: (212) 268-7474 f: (212) 268-7333 www.tstc.org.

19. World Economic Forum. 2018. Reshaping Urban Mobility with Autonomous

Vehicles – Lessons from the City of Boston. Geneva: World Economic

Forum, 2018. Available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Reshaping_Urban_Mobility_with_Autonomous_Vehicles_2018.pdf.

20. Zhang W., S. Guhathakurta, E.B.

Khalil. 2018. „The impact of private

autonomous vehicles on vehicle ownership and unoccupied VMT

generation”. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 90:

156-165. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2018.03.005.

21. Zhang W., S. Guhathakurta, J. Fang, G. Zhang.

2015. „Exploring the Impact of Shared

Autonomous Vehicles on Urban Parking Demand: An Agent-based Simulation

Approach”. Sustainable Cities and Society 19: 34-45. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2015.07.006.

22.

Zhang W., S. Guhathakurta. 2017. „Parking Spaces in the Age of Shared Autonomous Vehicles”. Transportation

Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2651: 80-91. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.3141/2651-09.

Received 15.07.2020; accepted in revised form 29.10.2020

![]()

Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License