Article

citation information:

Hudec, J., Šarkan, B., Caban,

J., Stopka, O. The impact of driving schools' training on fatal traffic accidents in

the Slovak Republic. Scientific Journal of

Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2021, 110, 45-57. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2021.110.4.

Juraj HUDEC[1],

Barnislav ŠARKAN[2],

Jacek CABAN[3],

Ondrej STOPKA[4]

THE

IMPACT OF DRIVING SCHOOLS' TRAINING ON FATAL TRAFFIC ACCIDENTS IN THE SLOVAK

REPUBLIC

Summary. This paper deals with

fatal traffic accidents in the period 2017-2019, caused by drivers who have

held driving licenses for less than five years. Specifically, it examines an

interconnection between these accidents and the driving schools being

completed by these drivers. Furthermore, it analyses whether the perpetrators

of traffic accidents with short driving experience are graduates of the same

driving schools, and thus, whether the occurrence of serious traffic accidents

is directly related to the quality of training in specific driving schools.

Keywords: road transport, road safety, accident rates,

drivers with short driving experience

1. INTRODUCTION

Every year,

the number of registered vehicles and traffic intensity increases, more and

more people get behind the steering wheeland become direct participants in road

traffic. Except for undoubted advantages, this causes a great growth of traffic

volume of the road network and a constantly increasing demand on traffic and

its safety [20,29,32]. Possession of a driving license and active utilisation

of a motor vehicle becomes an essential part of an individual’s daily

life. However, this is closely related to the increased risk of traffic

accidents, and unfortunately also those resulting in death. Road safety depends

on many factors, including the efficiency of the technical system and the

behaviour of the driver of the vehicle. Therefore, traffic accident rates

represent a serious societal problem with a huge impact on people's lives and

their property, hence, requires special attention [6,7,22]. Therefore, road

transport safety is a very complex issue, including the following factors:

technical [12,13,25], environmental [18,37,38], psychological [10,31], legal [14]

and socio-economic [17,23,33,35]. Besides, road transport safety is the subject

of activities of many states, social and international institutions.

Numerous

scientific publications have been devoted to the above-mentioned factors. For

example, Skrúcaný and Gnap [36] investigated dangers related to

heavy goods vehicle transportation under different loads and in varying

conditions of operating as well as during the braking process. In [12,13]

presents selected aspects of maintenance and reliability of vehicles safety

systems during its operation in a chosen transport company. Cernicky et al., [5]

suggest that one of the possibilities of reduction of the number of traffic

accidents in the Slovak Republic is the implementation of ITS on selected parts

of the road network. Jurecki et al., [18] investigated the behaviour of car

drivers in simulated surrounding situations of road traffic accidents. During

these tests, the simulation concerned a road traffic accident risk situation

involving pedestrians and passenger cars intruding into the road area. Ellison

et al., in work [16] identified drivers’ behaviours and their

relationship to the occurrence of a road traffic accidents risk. These

(individual) behavioural measures correctly predicted 68% of crash-involved

drivers (26 drivers) and 87% of non-crash-involved drivers (141 drivers) [16].

Road transport safety issues can be referred to as threats in the workplace,

especially in the case of professional drivers [24,30].

Alispahić

et al., [4], investigated the impact of young drivers training in the function

of road traffic safety. The education of drivers, especially younger ones, can

significantly affect road traffic safety and could contribute to environmental

protection as well as reduction of external costs [4]. Subsequently, an

accident rate of drivers with short driving experience has become a substantial

problem. According to statistics published by the Presidium of the Police Force

of the Slovak Republic [26-28], in a comparison of drivers depending on the

length of practice, showed that drivers holding driving licenses for less than

five years cause considerable fatal traffic accidents. The minimum limitation

for obtaining a driving license in the Slovak Republic is the age of 17.

Nevertheless, after obtaining a driving license, drivers do not have sufficient

experience in driving a motor vehicle, thus, becoming one of the riskiest

groups of drivers in the field of road safety [34]. In emergencies, driver

needs to make the right decision in a fraction of a second, which is related to

the reaction time. Such research was conducted, among others, by [15,19].

Since the

quality of training in driving schools is one of the factors affecting the

behaviour of this risky group of drivers and the occurrence of road traffic

accidents, the authors examine in this paper, the possible impact of driving

schools on road traffic accidents resulting in death.

2.

DATA AND METHODS

Driving

schools represent training and educational facilities registered under Act no.

93/2005 Coll. on driving schools (Act 93/2005 Coll., on driving schools) and on

the amendment of certain acts as amended [3]. Each driving school is registered

specially to provide education and training of participants in preparation for

an examination of professional competence for issuance of a license to drive

motor vehicles. A driving school is registered by the locally-competent

district office after fulfilling the stipulated legal conditions.

Such

a school must have a particular space at its disposal in which the driving

school operates, an office, a classroom, a training ground or a simulator,

training vehicles designed and approved to conduct courses for the group of

driving licenses for which the driving school is approved for [8].

Training

vehicles and driving school classrooms to ensure transparent training and

teaching (course) must be equipped with a permanently-mounted device enabling

data records on identity of the course participant and driving instructor

participating in practical training and theoretical course, and on journeys,

routes and driving times, times in classrooms as well as on the simulator. This

data is automatically transmitted from the devices to the Unified Road Traffic

Information System [1].

Every

single applicant for a driving license must undergo training in a driving

school to the extent being required. The scope and content of the course are

set out in the curriculum of driving courses issued by the Ministry of

Transport and Construction of the Slovak Republic [11]. The course is divided

into theoretical and practical parts. The duration of a driving course depends

on the group of driving licenses for which the training is being conducted. For

instance, for the most requested group of driving license B (passenger car), it

is mandatory to complete 32 teaching hours in terms of theoretical lessons and

39 teaching hours of practical driving experience (in cases that a driving school

disposes of a training ground). One lesson lasts 45 minutes.

2.1. Traffic

accidents in the Slovak Republic in the period 2017-2019

Given

the observed period of 2017, 2018 and 2019, accident rates in the Slovak

Republic and their consequences were as follows (Table 1) [26,28]:

Tab.

1

Traffic

accidents in the Slovak Republic in terms of

severity of consequences during the period 2017-2019

|

Traffic accidents / period |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

Total number of traffic accidents |

14,013 |

13,902 |

13,741 |

|

Number of traffic accidents resulting in death or

affecting health |

5,317 |

5,287 |

5,101 |

|

Number

of dead persons |

250 |

229 |

245 |

|

Number of severely injured persons |

1,127 |

1,052 |

1,050 |

|

Number of slightly injured persons |

5,757 |

5,623 |

5,515 |

The

major causes of fatal accidents are very similar and reoccur every year, they

are as follows [14,24,28]:

·

violation of driver's

duties (that is, failure to pay full attention to driving and negligence of

road traffic situations; not giving priority to pedestrians who enter the road

and passes a pedestrian crossing; driving under reduced ability due to

accident, illness, nausea or fatigue),

·

speeding,

·

inappropriate driving

method (style),

·

violation of special

provisions on pedestrians,

·

improper overtaking,

·

violation of the road traffic

user's obligation,

·

wrong turn,

·

incorrect driving through

an intersection,

·

incorrect turning and

reversing,

·

incorrect entry into the

road.

2.2. Analysis

of the impact of driving schools' training on fatal traffic caused by drivers

with short driving experience in the period 2017-2019

For

this study, data was requested from the Presidium of the Police Force of the

Slovak Republic, regarding drivers with driving experience of up to five years

who caused traffic accidents resulting in death in 2017, 2018 and 2019.

Subsequently, all the accident perpetrators underwent an investigation to

determine the driving school they completed their driving training. Specific

input data was recorded and consequently listed in Table 2-4. Due to personal

data protection, only data necessary for the examination was summarised in the

tables. For the sake of proper distinction, individuals who completed their

driving training in a driving school located in one district, have their

schools marked with particular letters within one table. However, If the symbol

† appears next to any of the data value, it means that the accident

perpetrator died in the accident.

Tab.

2

Traffic

accidents resulting in death caused by drivers with

driving experience up to five years in 2017

|

No. |

Year of birth of the traffic accident perpetrator

resulting in death |

Year of obtaining the driving license of the traffic

accident perpetrator resulting in death |

The seat of the driving school (district) in which

the perpetrator underwent driving training |

|

1. |

1979 |

2015 |

Senica (Driving school A.) |

|

2. |

1980 |

2016 |

Lučenec (Driving school A.) |

|

3. |

1981 |

2013 |

Žiar nad Hronom |

|

4. |

1984 |

2017 |

Nitra |

|

5. |

1984 |

2017 |

Nové Zámky |

|

6. |

1987 |

2015 |

Liptovský Mikuláš |

|

7. |

1988 |

2012 |

Trnava (Driving school A.) |

|

8. |

1989 |

2016 |

Dunajská Streda |

|

9. |

1990 |

2012 |

Dunajská Streda |

|

10. |

1991 |

2012 |

Michalovce |

|

11. |

1992 |

2012 |

Trnava (Driving school B.) |

|

12. |

1992 |

2016 |

Košice |

|

13. |

1992 |

2012 |

Trnava (Driving school C.) |

|

14. |

1992 |

2014 |

Žilina |

|

15. |

1992 |

2013 |

Senica (Driving school B.) |

|

16. |

1994 |

2015 |

Košice-suburb |

|

17. |

1994† |

2016 |

Čadca (Driving school A.) |

|

18. |

1995† |

2014 |

Banská Bystrica |

|

19. |

1995 |

2013 |

Ružomberok |

|

20. |

1995 |

2014 |

Poprad |

|

21. |

1995 |

2012 |

Čadca (Driving school B.) |

|

22. |

1995 |

2013 |

Kežmarok |

|

23. |

1996 |

2016 |

Veľký Krtíš |

|

24. |

1996 |

2014 |

Topoľčany |

|

25. |

1996 |

2014 |

Nové Mesto nad Váhom |

|

26. |

1996 |

2014 |

Považská Bystrica |

|

27. |

1996 |

2014 |

Humenné |

|

28. |

1996 |

2015 |

Trenčín |

|

29. |

1996 |

2015 |

Senec |

|

30. |

1997 |

2016 |

Prešov |

|

31. |

1997 |

2015 |

Zvolen |

|

32. |

1997† |

2016 |

Lučenec (Driving school B.) |

Table 2 shows that in 2017, 32 drivers with driving

experience less than five years caused traffic accidents resulting in death.

However, none of the perpetrators was a graduate of the same driving school;

that is, each of them completed driver training in different driving schools.

Tab.

3

Traffic accidents resulting in

death caused by drivers with

driving experience up to five years in 2018

|

No. |

Year of birth of the traffic accident perpetrator

resulting in death |

Year of obtaining the driving license of the traffic

accident perpetrator resulting in death |

The seat of the driving school (district) in which

the perpetrator underwent driving training |

|

1. |

1979 |

2015 |

Prešov (Driving school A.) |

|

2. |

1984 |

2015 |

Žilina (Driving school A.) |

|

3. |

1986† |

2015 |

Nitra (Driving school A.) |

|

4. |

1988 |

2015 |

Trnava |

|

5. |

1990† |

2015 |

Nové Zámky |

|

6. |

1993 |

2014 |

Žilina (Driving school B.) |

|

7. |

1993 |

2013 |

Dunajská Streda |

|

8. |

1993 |

2014 |

Prešov (Driving school B.) |

|

9. |

1994† |

2016 |

Michalovce |

|

10. |

1995† |

2017 |

Nitra (Driving school B.) |

|

11. |

1995 |

2013 |

Žilina (Driving school C.) |

|

12. |

1995 |

2013 |

Spišská Nová Ves |

|

13. |

1995 |

2015 |

Partizánske |

|

14. |

1996 |

2014 |

Nové Mesto nad Váhom |

|

15. |

1996 |

2015 |

Považská Bystrica |

|

16. |

1997 |

2015 |

Galanta |

|

17. |

1997 |

2015 |

Žiar nad Hronom |

|

18. |

1997 |

2014 |

Zvolen (Driving school A.) |

|

19. |

1997† |

2015 |

Topoľčany |

|

20. |

1998 |

2016 |

Žilina (Driving school D.) |

|

21. |

1998 |

2015 |

Myjava |

|

22. |

1988 |

2017 |

Komárno (Driving school A.) |

|

23. |

1998 |

2017 |

Humenné |

|

24. |

1998 |

2015 |

Zvolen (Driving school B.) |

|

25. |

1998 |

2016 |

Malacky |

|

26. |

1998† |

2016 |

Dunajská Streda |

|

27. |

1999 |

2017 |

Snina |

|

28. |

1999 |

2016 |

Komárno (Driving school B.) |

|

29. |

1999 |

2016 |

Kežmarok |

|

30. |

1999 |

2016 |

Košice-suburb |

From

the table above, it is clear that in 2018, 30 drivers with driving experience

of up to five years caused traffic accidents resulting in death. Nonetheless,

in analogy to the previous year, none of the perpetrators was a graduate of the

same driving school. Each completed driver training in different driving

schools.

Tab.

4

Traffic accidents resulting in death caused by drivers

with

driving experience up to five years in 2019

|

No. |

Year of birth of the traffic accident perpetrator

resulting in death |

Year of obtaining the driving license of the traffic

accident perpetrator resulting in death |

The seat of the driving school (district) in which

the perpetrator underwent driving training |

|

1. |

1980 |

2018 |

Banská Bystrica |

|

2. |

1981† |

2015 |

Zvolen |

|

3. |

1982 |

2014 |

Partizánske |

|

4. |

1983 |

2018 |

Bratislava |

|

5. |

1987 |

2017 |

Dolný Kubín |

|

6. |

1988 |

2018 |

Levice (Driving school A.) |

|

7. |

1989 |

2018 |

Kežmarok |

|

8. |

1990 |

2017 |

Humenné (Driving school A.) |

|

9. |

1991 |

2015 |

Humenné (Driving school B.) |

|

10. |

1992 |

2014 |

Partizánske |

|

11. |

1994 |

2018 |

Levice (Driving school B.) |

|

12. |

1994 |

2018 |

Žilina

(Driving school A.) |

|

13. |

1950 |

2014 |

Hlohovec |

|

14. |

1995 |

2014 |

Nové Mesto nad Váhom |

|

15. |

1995 |

2015 |

Nitra (Driving school A.) |

|

16. |

1995 |

2015 |

Nitra (Driving school B.) |

|

17. |

1995 |

2019 |

Žilina

(Driving school A.) |

|

18. |

1995 |

2014 |

Žilina (Driving school B.) |

|

19. |

1995 |

2015 |

Michalovce (Driving school A.) |

|

20. |

1996 |

2014 |

Prešov (Driving school A.) |

|

21. |

1996 |

2015 |

Prešov (Autoškola B.) |

|

22. |

1996 |

2014 |

Košice |

|

23. |

1997 |

2015 |

Trnava |

|

24. |

1997 |

2014 |

Trenčín |

|

25. |

1997 |

2015 |

Michalovce (Driving school B.) |

|

26. |

1998 |

2016 |

Považská Bystrica |

|

27. |

1998 |

2018 |

Košice-suburb (Driving school A.) |

|

28. |

1998 |

2016 |

Košice-suburb (Driving school B.) |

|

29. |

1998 |

2019 |

Krupina |

|

30. |

1999 |

2017 |

Galanta |

|

31. |

1999 |

2019 |

Dunajská Streda |

|

32. |

1999 |

2019 |

Nové Zámky |

|

33. |

1999 |

2017 |

Hlohovec |

|

34. |

2000 |

2019 |

Skalica |

|

35. |

2000 |

2019 |

Rimavská Sobota |

|

36. |

2001 |

2018 |

Trstená |

|

37. |

2001 |

2019 |

Revúca |

Table

3 presents 37 drivers with driving experience less than five years caused

traffic accidents resulting in death in 2019. Only two of these perpetrators

were graduates of the same driving school (marked in red).

The

data above confirms that from 2017 to 2019,a total of 99 traffic accidents were

caused by drivers with less than five years of driving experience. Each of the

perpetrators of these accidents was a graduate of a distinct driving school,

except for two of them who graduated in the same driving school. This involved

the district of Zilina; with one person graduating from this driving school in

2018 and the other in 2019. Both fatal traffic accidents occurred in 2019.

On

the one hand, from the examined sample of drivers with driving experience of up

to five years who caused traffic accidents resulting in death in 2017-2019, it

was almost not detected that they were graduates of the same driving schools;

therefore, some driving schools educate drivers who cause fatal traffic

accidents to an increased extent than others. On the other hand, the examined

data does not verify the quality of training in driving schools in the Slovak

Republic to be at a sufficient level or whether the reason for the high

incidence of fatal accidents among drivers with short driving experience needs

to be sought in driving schools. Given the fact that the perpetrators of these

accidents are mostly from different driving schools, the results of an analysis

being conducted may also indicate that there is a systemic lack in the training

quality [18].

Lastly,

in this context, it should be noted that the investigated sample of traffic

accident perpetrators are composed of respondents from the whole Slovak

Republic and was quite low compared to the total number of registered driving

schools in the Slovak Republic as well as the number of driving licenses being

issued. For illustration, the following table (Table 5) summarises the data on

the number of registered driving schools and the issued driving licenses in the

period of 2017-2019 [27].

Tab.

5

Number of registered driving schools and

issued driving licenses (2017-2019)

|

Year |

Number of registered driving schools |

Number of driving licenses being issued |

|

2017 |

615 |

147 042 |

|

2018 |

609 |

144 873 |

|

2019 |

603 |

149 322 |

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION – QUALITY OF

TRAINING IN DRIVING SCHOOLS

Each participant who has

undergone a driving school course training for driving a motor vehicle receives

a document from the driving school called “Certificate of Completion of

the Course”. This certificate is one of the documents to apply with in an

examination of professional competence of applicants for a driving license [2,9].

There is no formal difference among the certificates issued by the individual

driving schools, however, there may be huge differences among individual

driving training on which the certificates are issued. This lies in the quality

of training the driving school graduate paid for.

The quality of driving

school training cannot be formally measured. Rather, it is a kind of abstract

concept, which may be described by either individual preferences or general

interest. For example, from a driving course participant standpoint, a good

driving school is one, which has the lowest possible price, which he/she does

not have to attend and will provide him with a driving license. On the

contrary, in terms of the state, a good driving school is one that complies

with generally binding legal regulations, has its own suitable technical base

curriculum with experienced instructors, physically engaging participants in

driving courses where they receive full-featured driving training [18].

However, these preferences tend to be ambivalent. Participants cannot receive

high-quality training for a suspiciously low price for the course and vice

versa. Unfortunately, many participants are not aware of this simple rule, so

they prefer driving schools with a low-price course, even at the cost of the

negative consequences that may emerge from such a wrong choice [21]. Driving

schools are willing to meet their requirements and compete with each other in

not only prices, but also in the fact that the participant in the driving

course does not have to complete training at the driving school in full-range,

or even attend it at all. The low price of a driving course is usually

connected with non-participation in this training, which of course is illegal.

The results of the control activities of the Ministry of Transport and

Construction of the Slovak Republic in driving schools have constantly proven

this phenomenon.

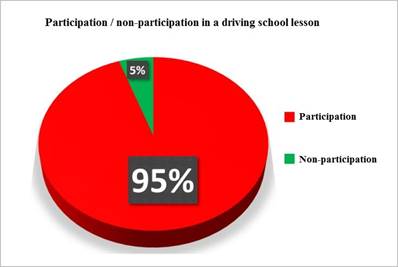

For instance, in 2019, in

driving schools, inspections for teaching the theoretical background were

conducted, discovering that 15 of 18 inspected classrooms of driving schools,

in which teaching the theory was supposed to take place, had no participant

present in them, and no full-participation was recorded in the remaining 3

classrooms. Of the total number of driving schools being inspected, in four

classrooms, no identification device was available, that is, participants were

fictitiously identified by driving school instructors from different

non-approved areas without their presence in the theoretical course of these

driving schools. From the conducted inspections, the total number of identified

persons was 169, while 160 of them were not present in the classrooms during

the inspection. These were random inspections of driving schools throughout the

Slovak Republic.

Fig. 1. Graphic

illustration of non-participation in driving school lesson found by

the Ministry of Transport and Construction of the Slovak Republic

Other negative facts found

out during the inspections include: a significant part of driving schools

carried out their practical driving courses in road traffic or in a training

ground without the physical participation of an identified participant in the

vehicle, with the instructor being alone in the driver's seat, or the persons

sitting in the vehicle misleadingly identified (the instructor was

identified as another instructor or as a course participant, etc.) [26,37].

Furthermore, inspections

conducted by the Ministry of Transport and Construction of the Slovak Republic

have confirmed that during 2018 and 2019, up to 265 participants in driving

courses did not complete training at all in three driving schools; yet, driving

licenses were issued to them. Courses and lessons related to teaching the

theory and practical training with these people were fictitiously reported and

not taught. In most cases, participants in such driving courses never attended

any driving school. After reporting the entire training, such

"graduates" were subsequently registered for examination of

professional competence of applicants for driving licenses. Fictitious courses

were conducted for passenger cars, trucks (freight vehicles), tractors,

motorcycles, as well as buses [26,28].

The inspections' findings in association with

driving schools in the Slovak Republic resulted in a statement that the high

incidence of fraud in this field is a long-term issue and, if this is defined

as one of the criteria for the quality of driving schools' training, then it is

not of a high level from this point of view. Although specific criteria for the

quality of driving schools' training are not clearly defined, it generally

applies that without the participation of students in driving training, grave

consequences would ensue.

4.

CONCLUSIONS

The paper aimed to

find out whether some driving schools, more than others, produce to an increased

extent, drivers who cause fatal accidents, and also whether the occurrence of

serious traffic accidents is directly related to the quality of training in

particular driving schools. The aforementioned was investigated on 99

perpetrators of traffic accidents resulting in death, caused from 2017 to 2019

by drivers who have held driving licenses for less than five years. An analysis

of the data being investigated showed that each of these accidents'

perpetrators was a graduate of a distinct driving school, except for two that

graduated from the same driving school. Concerning the rest, however, the occurrence

of this phenomenon is insignificant.

Following the above,

it has not been proven that some driving schools educate more drivers who cause

more fatal accidents than others do. Simultaneously, however, the analysis

findings may indicate that this involves a systemic shortcoming in the quality

of driving schools' training since the perpetrators of fatal traffic accidents

are mostly from numerous driving schools throughout the Slovak Republic. This

especially applies if the share of drivers with short driving experiences that

cause fatal accidents to other groups of drivers is high, as is the incidence

and severity of deficiencies identified in the operation of the driving

schools.

Many factors affect

the occurrence of fatal accidents. By identifying, recognising and analysing

them, as well as taking proper actions, it is possible to make some progress

towards eliminating their impact. As far as driving schools are concerned, in

addition to effective repression for violating legal regulations, one of the measures

could be, for example, a change in the curriculum of driving courses with

special emphasis on teaching and training in areas where the most common causes

of traffic accidents occur.

References

1.

Act no. 387/2015 Coll. on a

unified information system in road transport and on the amendment of

certain laws as amended.

2.

Act no. 8/2009 Coll. on Road

Traffic and on Amendments to Certain Acts, as amended.

3.

Act no. 93/2005 Coll. on driving

schools and on the amendment of certain laws as amended.

4.

Alispahić Sinan, Zeljko Antunović,

Ekrem Bećirović. 2007. „Training of drivers in the function

of road traffic safety”. Promet-Traffic&Transportation

19(5): 323-327. DOI: 10.7307/ptt.v19i5.967.

5.

Cernicky Lubomir, Alica Kalasova, Jerzy Mikulski.

2016. „Simulation software as a calculation tool for traffic

capacity assessment”. Communications

– Scientific Letters of the University of Zilina (Komunikacie) 18(2): 99-103.

6.

Chovancova Maria, Klapita Vladimir. 2017.

„Modeling the supply process using the application of selected

methods of operational analysis”. Open

Engineering 7(1): 50-54. DOI: 10.1515/eng-2017-0009.

7.

Dabbour Essam, Abdallah Badran. 2020.

„Understanding how drivers are injured in rear-end collisions“. European Transport \ Trasporti Europei

77 n. 1.

ISSN: 1825-3997.

8.

Decree no. 45/2016 Coll., Which

implements Act no. 93/2005 Coll. on driving schools and on the amendment of

certain laws as amended.

9.

Decree no. 9/2009 Coll., Which

implements the Act on Road Traffic and on Amendments to Certain Acts.

10.

Distefano Natalia, Salvatore Leonardi, Giulia

Pulvirenti, Richard Romano, Natasha Merat, Erwin Boer, Ellie Woolridge.

2020. „Physiological and driving behaviour changes associated to

different road intersections“. European

Transport \ Trasporti Europei 77 n. 4. ISSN: 1825-3997.

11.

Driving curricula issued by the Ministry of Transport

and Construction of the Slovak Republic.

12.

Droździel Paweł, Iwona Rybicka,

Radovan Madlenak, Aleksandra Andrusiuk, Dariusz Siłuch. 2017. „The

engine set damage assessment in the public transport vehicles”. Advances in Science and Technology –

Research Journal 11(1): 117-127. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.12913/22998624/66502.

13.

Droździel Paweł, Leszek Krzywonos. 2009.

„The estimation of the reliability of the first daily diesel engine

start-up during its operation in the vehicle”. Eksploatacja i Niezawodnosc – Maintenance and Reliability

41(1): 4-10.

14.

Droździel Paweł, Rafał Wrona. 2018.

„Legal and utility problems of accidents on express roads and

motorways”. 11th International

Science and Technical Conference Automotive Safety. Casta, Papiernicka,

Slovakia. 18-20 April 2018. P. 1-5. DOI: 10.1109/AUTOSAFE.2018.8373315.

15.

Droździel Paweł, Sławomir

Tarkowski, Iwona Rybicka, Rafał Wrona. 2020. „Drivers' reaction

time research in the conditions in the real traffic”. Open Engineering 10(1):

35-47. DOI: 10.1515/eng-2020-0004.

16.

Ellison Adrian, Stephen P. Greaves, Michiel C.J.

Bliemer. 2015. „Driver behaviour profiles for road safety

analysis”. Accident Analysis &

Prevention 76: 118-132. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2015.01.009.

17.

Fabianova Jana, Peter Kacmary, Vieroslav Molnar, Peter

Michalik. 2016. „Using a software tool in forecasting: a Case Study

of sales forecasting taking into account data uncertainty”. Open Engineering 6: 270-279. DOI:

10.1515/eng-2016-0033.

18.

Jurecki Rafał Stanisław, Milos

Poliak, Marek Jacek Jaskiewicz. 2017. „Young adult drivers: simulated behaviour

in a car-following situation”. Promet-Traffic

& Transportation 29(4): 381-390. DOI: 10.7307/ptt.v29i4.2305.

19.

Jurecki Rafał Stanisław, Tomasz

Lech Stańczyk, Marek Jacek Jaśkiewicz. 2017. „Driver's reaction

time in a simulated, complex road incident”. Transport 32(1): 44-54. DOI: 10.3846/16484142.2014.913535.

20.

Kalašová Alica, L’ubomír

Černický, Milan Hamar. 2012. „A new approach to road safety

in Slovakia”. 12th International

Conference on Transport Systems Telematics. Katowice Ustron, Poland. Oct.

10-13, 2012. Telematics in the Transport Environment. Edited by: Mikulski J. Communications in Computer and Information

Science 329: 388.

21.

Kampf Rudolf, Jan Lizbetin, Lenka Lizbetinova. 2012.

„Requirements of a transport system user”. Communications – Scientific Letters of the University of Zilina

(Komunikacie) 14(4): 106-108. ISSN: 1335-4205.

22.

Kohút Pavol, Ľudmila Macurová,

Miroslav Rédl, Michal Ballay. 2020. „Application of rectification

method for processing of documentation from the place of road accident”. The Archives of Automotive Engineering

– Archiwum Motoryzacji 88(2): 37-46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14669/AM.VOL88.ART3.

23.

Konečný Vladimir, Ivana

Šimková, Lenka Komačková. 2015. „The accident

rate of tourists in Slovakia”. Logi

- Scientific Journal on Transport and Logistics 6(1):

160-171. ISSN: 1804-3216.

24.

Kubáňová Jaroslava, Bibiana

Poliaková. 2016. „Truck driver scheduling of the rest period as an

essential element of safe transport”. 20th

International Scientific on Conference Transport Means 2016. P. 22-26.

Juodkrante, Lithuania. 5-7 October 2016. ISSN: 1822-296X.

25.

Lizbetin Jan, Ladislav Bartuśka. 2017. „The

influence of human factor on congestion formation on urban roads”. 10th International Scientific Conference

Transbaltica 2017, Transportation Science and Technology, Procedia Engineering

187: 206-211. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.04.366.

26.

Ministry of Interior of the Slovak Republic.

“Complete statistics”. Available at:

https://www.minv.sk/?kompletna-statistika.

27.

Ministry of Interior of the Slovak Republic.

“Statistical overviews of the agenda of drivers and driving

licenses”. Available at:

https://www.minv.sk/?statisticke-prehlady-agendy-vodicov-a-vodicskych-preukazov.

28.

Ministry of Interior of the Slovak Republic.

“Traffic accident in the Slovak Republic”. Available at: https://www.minv.sk/?statisticke-ukazovatele-sluzby-dopravnej-policie.

29.

Mphela Thuso. 2020. „Causes of road accidents

in Botswana: An econometric model”. Journal

of Transport and Supply Chain Management 14: a509. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4102/jtscm.v14i0.509.

30.

Mračková Eva, Milos Hitka, Robert

Sedmák. 2014. „Changes of anthropometric characteristics of the

adult population in Slovakia and their influence on material sources and work

safety”. Advanced Materials

Research 1001, Trans Tech Publications: 401-406. ISSN: 1022-6680.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1001.4.

31.

Ondrus Jan, Grzegorz Karoń. 2017. „Video

system as a psychological aspect of traffic safety increase”. 17th International Conference on Transport

Systems Telematics (TST). Katowice, Poland. April 05-08, 2017. Communications in Computer and Information

Science 715: 167-177. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66251-0_14.

32.

Patkar Manish, Ashish Dhamaniya. 2019.

„Effect of On-street parking on Effective Carriageway Width and Capacity of

Urban Arterial Roads in India“. European

Transport \ Trasporti Europei 73 n. 1. ISSN: 1825-3997.

33.

Poliakova Bibiana, Józef Stoklosa. 2016.

„The impact of proposed prices on the public transport providers and

passengers for integrated transport system in Kosice region”. Communications – Scientific Letters of

the University of Zilina (Komunikacie) 18(2): 133-138. ISSN: 1335-4205.

34.

Proposal of a strategy to increase road safety in the

Slovak Republic in the years

2021-2030 (Národný plán SR pre BECEP 2021-2030).

35.

Simanová Ľubica, Renata

Stasiak-Betlejewska. 2018. „Selected approaches to change management

and logistics in Slovak enterprises”. LOGI

– Scientific Journal on Transport and Logistics 9(2): 51-60. DOI:

10.2478/logi-2018-0018.

36.

Skrúcaný Tomas, Jozef Gnap. 2014.

„The effect of the crosswinds on the stability of the moving

vehicles”. 6th International

Scientific Conference on Dynamic of Civil Engineering and Transport Structures

and Wind Engineering, Applied Mechanics and Materials 617: 296-301.

37.

Skrucany Tomas, Martin Kendra, Tomáš

Kalina, Martin Jurkovič, Martin Vojtek, František Synák. 2018.

„Environmental comparison of different transport modes”. Nase More 65(4): 192-196. ISSN:

0469-6255. DOI: 10.17818/NM/2018/4SI.5.

38.

Skrúcany Tomas, Stefania Semanova, Tomasz

Figlus, Branislav Šarkan, Jozef Gnap. 2017. „Energy intensity and

GHG production of chosen propulsions used in road transport”. Communications – Scientific Letters of

the University of Zilina (Komunikacie) 19(2): 3-9. ISSN: 1335-4205

Received 20.07.2020; accepted in revised form 25.10.2020

![]()

Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License