Article

citation information:

Hanusik, A. Identification and risk

assessment in carsharing. Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2020, 109, 33-43. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2020.109.3.

Andrzej HANUSIK[1]

IDENTIFICATION

AND RISK ASSESSMENT IN CARSHARING

Summary. There are many new

concepts for doing business in the modern market. Carsharing is one of such

models that are directly related to the sharing economy. The current body of

literature shows an absence of reports about risk management in carsharing

operators. Further investigation of scientific databases confirms the existence

of a research gap in this field. The purpose of this article is for

identification of risks in carsharing and their latter assessment in terms of

probability of occurrence, impact on customer relationships, the importance of

a given category and the cost they generate. A way of aggregating various

categories of risks into one synthetic indicator to prioritise them was

proposed. The methodology of the process was based on a methodological

triangulation which is established on the following studies – analysis

and criticism of literature which helps to place discussed research problems on

a theoretical basis, qualitative research and observations allowing to identify

individual categories of risks and quantitative research enabling the

description of given categories of risks by appropriate variables on which

further risk modelling is performed. Such research may be a basis for

subsequent analysis and an impulse to an academic debate. Besides, it may

contribute to the creation of further studies, which deal with the problem

of assessment of the risk in concepts related to sharing economy.

Keywords: sharing economy, carsharing, risk assessment

1. INTRODUCTION

The modern market has a

very dynamic composition, which forces the search for newer and more innovative

solutions. Current situation brings many changes – both related to the

purely practical business environment and the field of economic sciences.

Certainly, it can be assumed that the advantage of the modern world is the

creativity of business entities and consumers, and thus, innovations that are

present on the free market (reflected by actions of enterprises or market-based

organisations) [1] on the non-market social level (both individual and group)

and even in the sector of government entities [2]. Globalisation and extremely

rapid development of technologies can be considered as factors of these

changes. Furthermore, these factors drive the world towards an increasingly

homogenous community. These changes concern not only the way of communication,

increasing mobility or standardisation of offered products but also the way of

thinking (economic, social and cultural). This situation prompted the emergence

of new concepts of offering using services or items on the market.

Increasingly, the

phenomenon of the shift in the focus of approach to economic goods is noticed

in the business models of enterprises and the consumption behaviour of people.

Business entities are realising a growing awareness of the fact that access to

a given good rather than the necessity of possessing it, is more economically

effective. Sharing economy is a process involving the joint use of goods by

many entities, extended by the aspect of engaging in joint activities [3].

Therefore, the traditional approach to market exchange, where ownership is,

above all, an unlimited possibility to dispose of the good by its owner and a

possibility of creating some kinds of boundaries for other entities that do not

have such good, hence, restricting access, renting or selling the good [4].

The phenomenon of

sharing economy is undeniably associated with market growth, which is being

progressively discussed by academics and businesspersons. The popularity of the

concept and constantly growing pace of solution in this area influences the

change of currently operating business models of enterprises. Sharing economy

is based on transactions related to granting access to a given good without

transferring ownership to it. Hence, the entity receives only a certain unit of

time specified in a contract, in which it can use the given food; acquires the

right to temporary usage [5]. This approach allows the use of certain goods by

entities that would not be able to buy them. This situation allows increasing

the productivity of the economy (by increasing the possibilities for individual

entities) and contributes to minimising the phenomenon of exclusion. The

weakness of this concept lies in the anonymity of entities using a shared good

(in some cases) and the possibility of improper use of the good. Consequently, there

is a risk that the entity, which only uses a given good, may not care for it as

much as in the situation that it owns it. This may result in decreasing the

quality of commonly used goods or services. Accordingly, this situation can be

observed in the case of goods shared by people rather than by enterprises.

Carsharing is one

element of the sharing economy. Carsharing consist of a paid access to a car,

which is not fully used by its owners (in case of private carsharing) or to a

specially adapted vehicle for a short rental (in case of business carsharing).

Access to vehicles is based on one-time or periodic payments. Cars are almost

only used for short local journeys, as renting a car for a longer period

attracts very high costs [6]. The whole transaction is concluded and settled

using a dedicated application, so there is no need for direct contact with the

client. The use of a sharing economy (including carsharing), in urban areas,

may contribute to the improvement of the transport situation in the given area;

transport will become cleaner, more intelligent and more sustainable. More so,

the mobility behaviour of citizens and business entities would change, which

will contribute to increasing the efficiency usage of infrastructure and

reduction of cost [7]. Such a solution is a very convenient form for

consumers; however, it is associated with an increased risk for the entity

offering the carsharing services.

It can be presumed that

concepts related to sharing economy will develop dynamically in the future. It

is related to the market itself and the nature of the Y-generation who are

increasingly active on the market. This generation is keen on searching for

innovative solutions, thus, they wholly embrace the sharing economy.

Additionally, the Y-generation are eager to take risky actions [8], which

impacts on the costs and risk bore by carsharing operators. Therefore, it is

necessary to identify risky activities and the probability of their occurrence

for entities offering carsharing services to create an efficient and effective

risk management system

2. METHODOLOGY AND DATA

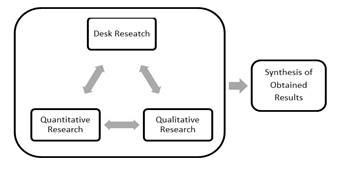

The research methods and

techniques used in this work were based on methodological triangulation (Figure

1). The structure of the study allowed for an in-depth analysis of the problem

and for obtaining more reliable conclusions.

Fig. 1.

Methodological triangulation used in this study

In the first part of the

article, the method of analysis and criticism of literature (desk research) was

used. It includes a systematic and orderly study of previous scientific works

and existing publication resources [9]. The use of this method allowed the

identification of the research problem and defined ways to solve it.

Furthermore,

observations were made to identify risks that occur in carsharing activities.

This method consists of discreet observation of people using carsharing, their

behaviour when renting a vehicle, its use and return. This allowed identifying

the types of risks to be considered in the risk analysis.

Thereafter, the IDI

(Individual In-depth Interview) method was used. In-depth interview is a

qualitative research technique, which involves conducting intensive individual

interviews with a small number of respondents. The result of the interviews

provides information about their knowledge and point of view on the selected

topic. IDIs are used in the case of new research problems that were not

previously scientifically discussed or were discussed superficially [10].

In-depth interviews were conducted with carsharing users, sharing economy

experts, and carsharing services providers. The structure of the interviews was

semi-structured (respondents were asked questions following the prepared

scenario with freedom of expression allowed). Conducted interviews allowed the

identification of subsequent risk categories and their initial assessment.

The last step related to

collecting data was surveying the assessment of individual risk categories in

terms of likelihood of their occurrence, impact on customer relations (if

detected by the customer) and a subjective indication of a maximum of three

risks most relevant to carsharing activities. Overall, 528 people took part in

the survey (snowball sampling). The survey was conducted from October 1, 2019,

to October 22, 2019, using paper and online forms. Fourteen surveys were

rejected due to wrong filling, lack of information or illegibility.

Next, based on previous

steps and additional analyses, individual risk categories were assessed in

terms of the following indicators:

-

X1

– probability

of risk occurrence (expressed in the form of assessments obtained through

surveys), where:

o 1 – very low probability of

occurrence,

o 2 – low probability of occurrence,

o 3 – average probability of

occurrence,

o 4 – high probability of occurrence,

o 5 – very high probability of

occurrence.

-

X2

– impact on relations with customers (expressed in the form of

assessments obtained through surveys), where:

o 1 – very large negative impact,

o 2 – large negative impact,

o 3 – medium negative impact,

o 4 – little negative impact,

o 5 – very little negative impact.

-

X3

– significance of a given risk category - number of survey responses

(expressed in%).

-

X4

– costs associated with the occurrence of a given risk - to determine the

most likely cost associated with the occurrence of a given risk (Co), a triple estimation was used (following the PERT

methodology). Optimistic (Cc), most likely (Cm) and pessimistic (Cp) cost

values were adopted for each risk. The value was received via IDIs. The

expected value of the beta distribution was calculated from the formula [11]:

![]() (1)

(1)

Thereafter, the

calculation of key risks in carsharing activities was made. First, the

assignation of superior importance indicators and lesser importance indicators

for the carsharing enterprises were made. The weights were determined by

analysing in-depth interviews with representatives of carsharing companies. It

should be noted that each risk category has been described by four indicators,

which are characterised by different units and the values associated with the

highest level of risk in individual categories, once strive for maximum, once

for minimum. This situation required aggregating all indicators into one

synthetic indicator (Si), which allowed obtaining comparable results:

![]() (2)

(2)

where X’ij represents aggregated

values for individual indicators. Aggregated values were calculated from the

formulas:

![]() (3)

(3)

or

![]() (4)

(4)

where Xij is the indicator value for a

particular risk category. The maximum value means that the highest score is

associated with the highest risk, whereas, the minimum, the lowest score is the

highest risk.

It is likewise worth

noting that:

![]() (5)

(5)

To simplify the

calculation, the weight values for individual indicators have been allocated

using the percentage presented in decimal form:

![]() (6)

(6)

Thus, the formula for the synthetic

indicator has been simplified to the form:

![]() (7)

(7)

The procedure carried

out in this way leads to the aggregation of individual indicators into one

synthetic indicator, which allows for prioritising individual risk categories

and placing them in the strategy of a carsharing company.

3. RESULTS

Through the observations

and individual in-depth interviews (IDI), the following types of risk have been

identified to occur in carsharing:

-

Y1 –

vehicle theft – for the analysis, one of the most popular passenger

carsharing vehicles in Poland (Renault Clio) was selected. For example, it is

used by Traficar [12];

-

Y2 –

gasoline theft – the vehicle is not serviceable, it is necessary to

refuel and possibly tow;

-

Y3 –

total damage of the vehicle – the car is not capable of further use;

-

Y4 –

partial damage of the vehicle – the vehicle is capable of further use

after making the necessary repairs;

-

Y5 –

leaving the vehicle in a dangerous place – generates the risk of damage

or theft - direct costs associated with the necessity

of moving the vehicle or are connected with

lost sales opportunities;

-

Y6 –

leaving the vehicle in an unauthorised place – the risk of receiving a ticket, towing away or

damaging it;

-

Y7 –

dirty exterior of the car – the risk of losing customers and incurring

washing costs;

-

Y8 –

dirty

interior of the car – the risk of losing customers and incurring

cleaning costs;

-

Y9 –

running out of gasoline/discharging an electric vehicle during use – the

risk of losing customers, towing costs;

-

Y10 –

mobile application problems – the risk of losing customers;

-

Y11 –

making the vehicle available to third parties – the possibility of

damage, the problem with debt collection;

-

Y12 –

driving in a state of intoxication – the possibility of damage, the risk

of losing customers, negative opinions from customers;

-

Y13 –

counterfeit documents during registration – a problem with establishing

the driver's identity and with debt collection;

-

Y14 –

lack of funds for service fee - freezing capital, the need to start the debt

collection.

Categories of risk

listed above were assessed by respondents in terms of three measures and

supplemented by the estimation of costs associated with their occurrence. The

costs were estimated based on the real value of the vehicles, their equipment,

fuel prices or costs related to transport-related services; cleaning, towing,

repairs or costs of the debt collection process. Table 1 shows the results of

the conducted research (rounded to two decimal places).

Tab. 1

Research results

|

|

mX1 max |

mX2 min |

mX3 [%] max |

X4

[PLN] max |

|

|

Y1 |

2,58 |

1,93 |

37,88 |

Cc = 20 000; Cm= 50 000;

Cp = 60 000 the cost depends on

the age and condition of the car |

Co ≈ 46 667 |

|

Y2 |

2,69 |

2,31 |

12,12 |

Cc = 150; Cm= 250; Cp =

500 the cost depends on

the price of gasoline and the need for towing |

Co ≈ 275 |

|

Y3 |

3,00 |

1,75 |

41,67 |

Cc = 20 000; Cm= 50 000;

Cp = 60 000 the cost depends on

the age and condition of the car |

Co ≈ 46 667 |

|

Y4 |

3,92 |

2,08 |

48,48 |

Cc = 2 000; Cm= 5 000; Cp

= 20 000 the cost depends on

the scale of damage |

Co ≈ 7 000 |

|

Y5 |

3,53 |

2,62 |

21,97 |

Cc = 20; Cm= 50; Cp =

200 the cost of moving the

vehicle and loss of customers |

Co ≈ 70 |

|

Y6 |

3,77 |

2,74 |

25,00 |

Cc = 20; Cm= 100; Cp =

1 000 the cost of moving,

towing away, parking and loss of customers |

Co ≈ 237 |

|

Y7 |

4,02 |

3,55 |

3,03 |

Cc = 10; Cm= 30; Cp = 80 the cost of travelling

to the car wash and washing |

Co ≈ 35 |

|

Y8 |

4,01 |

2,88 |

21,97 |

Cc = 100; Cm= 250; Cp =

1 000 the cost of travelling

and cleaning service |

Co ≈ 350 |

|

Y9 |

3,40 |

2,39 |

11,36 |

Cc = 50; Cm= 100; Cp =

300 the cost of towing and

loss of customers |

Co ≈ 125 |

|

Y10 |

3,19 |

2,44 |

23,48 |

Cc = 30; Cm= 300; Cp =

5 000 the cost of losing

customers |

Co ≈ 1 038 |

|

Y11 |

3,23 |

2,83 |

18,94 |

Cc = 0; Cm= 30; Cp = 150 the cost of

non-payment, debt collecting and loss of customers |

Co ≈ 45 |

|

Y12 |

3,08 |

2,23 |

16,67 |

Cc = 0; Cm= 30; Cp = 1

000 the cost of

non-payment and a lawsuit |

Co ≈ 187 |

|

Y13 |

2,65 |

2,48 |

15,15 |

Cc = 0; Cm= 30; Cp =

1 000 the cost of

non-payment and possible damage |

Co ≈ 1 687 |

|

Y14 |

2,92 |

2,82 |

2,27 |

Cc = 0; Cm= 30; Cp = 100 the cost of

non-payment |

Co ≈ 37 |

The values of the X1, X2 and X3 measures presented in the table are the values

obtained in the survey. Costs are indicative values, which should be considered

individually in each case. Nevertheless, certain values must be adopted to

conduct a risk analysis. Their size depends primarily on the scale of the

problem or the occurring abuses. The values of individual measures were

estimated using IDI. Triple cost estimation was used to best fit the model to

reality.

The next part of the

research was to calculate the value of the synthetic indicator. The following

weights of individual factors were adopted in this study: w1 = 0.30; w2 = 0.20;

w3 = 0.20; w4 = 0.30. The base for establishing the weights of individual

factors were the expectations of the carsharing companies. According to IDIs, the

costs and probability of risk occurrence are the most important (they

constitute 60% of weight). Customer relations (the X2 and X3

measures) represent 20% in the analysis (10% per gauge). Table 2 presents the

results of the conducted analysis (to obtain more accurate results, the values

of the calculated indices have been rounded to four decimal places).

Tab. 2

Synthetic indicator results

|

|

X1 w1 =

0,30 |

X2 w2 =

0,20 |

X3 w3 =

0,20 |

X4 w4 =

0,30 |

∑ |

|

Y1 |

0,1925 |

0,1813 |

0,1563 |

0,3000 |

0,8301 |

|

Y2 |

0,2007 |

0,1515 |

0,0500 |

0,0018 |

0,4040 |

|

Y3 |

0,2239 |

0,2000 |

0,1719 |

0,3000 |

0,8958 |

|

Y4 |

0,2925 |

0,1683 |

0,2000 |

0,0450 |

0,7058 |

|

Y5 |

0,2634 |

0,1336 |

0,0906 |

0,0004 |

0,4880 |

|

Y6 |

0,2813 |

0,1277 |

0,1031 |

0,0015 |

0,5136 |

|

Y7 |

0,3000 |

0,0986 |

0,0125 |

0,0002 |

0,4113 |

|

Y8 |

0,2993 |

0,1215 |

0,0906 |

0,0022 |

0,5136 |

|

Y9 |

0,2537 |

0,1464 |

0,0469 |

0,0008 |

0,4478 |

|

Y10 |

0,2381 |

0,1434 |

0,0969 |

0,0067 |

0,4851 |

|

Y11 |

0,2410 |

0,1237 |

0,0781 |

0,0003 |

0,4431 |

|

Y12 |

0,2299 |

0,1570 |

0,0688 |

0,0012 |

0,4569 |

|

Y13 |

0,1978 |

0,1411 |

0,0625 |

0,0108 |

0,4122 |

|

Y14 |

0,2179 |

0,1241 |

0,0094 |

0,0002 |

0,3516 |

The conducted analysis

allows for prioritising individual risk categories in terms of their importance

for carsharing companies. The analysis methodology presented in this work can

be a starting point for further in-depth research. Moreover, the results obtained

may be the starting point for creating risk management strategies for

carsharing companies.

4. DISCUSSION

After the analysis,

individual risk categories were ordered according to their importance for the

risk management strategy of carsharing enterprises. Table 3 presents values of

the synthetic measure in a hierarchical order.

Tab. 3

Synthetic

indicator results in

descending order

|

Y3 |

0,8958 |

|

Y1 |

0,8301 |

|

Y4 |

0,7058 |

|

Y6 |

0,5136 |

|

Y8 |

0,5136 |

|

Y5 |

0,4880 |

|

Y10 |

0,4851 |

|

Y12 |

0,4569 |

|

Y9 |

0,4478 |

|

Y11 |

0,4431 |

|

Y13 |

0,4122 |

|

Y7 |

0,4113 |

|

Y2 |

0,4040 |

|

Y14 |

0,3516 |

The key risks for

carsharing companies were total vehicle damage (Y3), vehicle theft

(Y1) and partial vehicle damage (Y4). This situation is

associated with the higher costs of these events, in this case, a good solution

is vehicle insurance and a record in the regulations about the assignation of

costs related to vehicle damage to the consumer, such solutions are practically used in all carsharing companies, that is,

Traficar [13], Panek [14] or Drive Now [15]. The fee is usually transferred to

the user in a situation when there is a necessity of paying a parking fee (Y6),

cleaning the car (Y8) or when an unauthorised person drives a

vehicle (Y11).

Leaving the vehicle in a

dangerous place (Y5) may similarly be a big problem, as this may

result in damage to the vehicle or loss of customers. The solution may be the

so-called "cutting out zones", that is, determining areas in which

the car cannot be left unattended.

Application issues (Y10)

are very important problems. Although they are not associated with high costs,

they have a relatively large impact on the relationship with customers.

Moreover, according to the conducted research, problems with applications

happen at times, which also has an impact on the company's image.

Driving in a state of

intoxication (Y12) is a very big problem for road safety.

Furthermore, carsharing vehicles are often available in entertainment

districts, which may encourage inebriated people to use them, for example, when

returning home. It should be noted that driving in the state of intoxication is

not a very important risk for carsharing companies, in the event of an

accident, collision or dirt, the driver is held liable. Nevertheless,

preventive actions may be part of the CSR strategy of carsharing operators.

Running out of gasoline

or discharging an electric car (Y9) during usage of the vehicle is

unlikely. This situation is caused by a lack of care on the part of the

enterprises to constantly supplement them. However, it should be noted that

when such a situation occurs, it could contribute to significant traffic difficulties,

negative opinion about the entrepreneur, and in the worst case, even to a

collision or accident.

The use of counterfeit

documents during registration (Y13) is not a common situation.

Although, it may lead to problems with determining the driver's data and the

subsequent recovery of receivables, nevertheless, carsharing companies often

protect themselves in an additional way, the second stage of verification is

the need to connect to the credit card system and / or make a small amount

transfer. Such activities significantly impede the provision of false data.

However, they do not protect the enterprise against possible losses related to

the collection of receivables due to lack of funds for travel (Y14).

However, the losses, in this case, are small. More so, usually after sending a

reminder, the customer decides to pay. Nevertheless, in some cases it is

necessary to start the debt collection process, which is not profitable for

small amounts (such as those usually associated with car journeys for minutes),

which may result in the operator's unwillingness to initiate proceedings; the

case will probably result in blocking the account. However, these small

unrecovered amounts do not affect the overall balance of the enterprise (the

effect of scale works here), besides, they are also not often encountered,

which is the reason this risk was ranked last in the hierarchy.

The dirty exterior of

the car (Y7) is the situation with the highest probability of

occurrence. Whereas the costs associated with levelling it are small, and the

mere contamination of the car body does not affect the customer's decision to

rent the car. The standard public approach is the fact that cars are utility

items that could get dirty. Moreover, soiling the outside of the car does not

affect the comfort of travelling (unless the windows, lights or mirrors are

dirty).

Gasoline theft (Y2)

in modern times is quite a common situation (especially in transport

companies). This situation is primarily related to gasoline prices, a strong

correlation can be observed between the number of thefts and the price of

gasoline [16]. Nevertheless, there are many effective methods to prevent theft.

Additionally, vehicles of the carsharing fleet are constantly monitored, so

thieves prefer to steal from private cars.

5. CONCLUSION

The analysis allowed

obtaining a catalogue of risks related to carsharing activities and prioritise

them in terms of importance for operators. To the best of the author's

knowledge, no article dealing with these issues has been published before now.

The author is also aware of the diversity of expectations of individual operators,

which means that the conducted research indicates only the most important

factors in the industry. Moreover, the choice of measures for assessing

individual risk categories depends on the individual preferences of operators.

Nevertheless, the analysis may prove to be the foundation for further research

and provide a starting point for creating risk assessment strategies in

carsharing activities.

Furthermore, it should

be noted that each analysis is tailored to a specific market. The approach of

customers, the likelihood of a given risk or prices may vary depending on the

geographical location, the economic system of the given country or cultural

conditions. This analysis is adapted to the specifics of the Polish market;

however, some features may be common with other areas.

The author's goal was to

identify the research gap regarding the concept of sharing economics and

initiate an academic debate on this topic. This article is to constitute an

introduction to further extended research in this field.

References

1.

Amabile T. M. Creativity and Innovation in Organizations. Harvard Business School

Background Note. 1996. No. 396-239. 123 P.

2.

Paulus P., B.M. Dzindolet. 2008.

“Social Influence, Creativity and Innovation”. Social Influence 3(4): 228-229.

3.

Felson M., J. Spaeth. 1978. „Community

Structure and Collaborative Consumption: A Routine Activity Approach”.

The American Behavioral

Scientist

21(4): 614.

4.

Rudawska I. 2016. „Ekonomia

dzielenia się, czyli konsumpcja współdzielona i inne formy

alternatywnego dostępu do dóbr”. Studia Ekonomiczne. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w

Katowicach 254: 183-184. [In

Polish: „Sharing Economy – Collaborative Consumption and Other Forms of

Access-based Consumption”. Economic

Studies. Scientific Notebooks of the University of Economics in Katowice].

5.

Lovelock Ch., E. Gummesson. 2004. “Whither Service Marketing? In

Search of a New Paradigm and Fresh Perspectives”. Journal of Service Research 7(1): P. 29.

6. Bardhi F., G.M. Eckhardt.

2012. “Access-Based Consumption: The Case of Car Sharing”. Journal of Consumer Research 39(4): P.

886.

7. Flügge B. 2017. Smart Mobility – Connecting Everyone.

Trends, Concepts and Best Practices. Wiesbaden: Springer Vieweg.

8. Hanusik A.

“Y-generation's Perception of Sharing Economy”. 12th International Scientific Conference

“Analysis of International Relations 2019. Methods and Models of Regional

Development”. Conference Proceedings. Katowice, 2019. P. 5-16.

9. Cisek S. 2010. „Metoda analizy i krytyki

piśmiennictwa w nauce o informacji i bibliotekoznawstwie w XXI

wieku”. Przegląd Biblioteczny 3: P. 273-284. [In Polish: “Methods of Literature Analysis and Criticismin

Library and Information Ccience in

21st Century”. Library Review].

10. Boyce C., P. Neale.

2006. “Conducting In-depth Interviews: A Guide for Designing and

Conducting In-Depth Interviews for Evaluation Input”. Pathfinder International Tool Series.

Monitoring and Evaluation 2: P. 3-12.

11. Patan M. „Badania

operacyjne. Programowanie sieciowe. Metoda PERT”. Instytut Sterowania i

Systemów Informatycznych. Uniwersytet

Zielonogórski. Available at:

http://staff.uz.zgora.pl/mpatan/materialy/badoper/wyklady/druk_5d.pdf [In Polish: “Operations research. Network programming. PERT

method”. Institute of Control and

Information Systems. University of Zielona Góra].

12. Flota Traficara - samochody osobowe. Traficar.

Available at: https://www.traficar.pl/cars [In Polish: Traficara fleet -

passenger cars].

13. Regulamin korzystania z usługi Traficar. Traficar. Available at: https://www.traficar.pl/regulamin/pl/regulamin.html [In Polish: Regulations of using

the Traficar service].

14. Regulamin Panek S.A. w zakresie

najmu samochodów. Panek. Available at:

https://www.ipanek.pl/sites/all/pliki/regulamin_rac_6.03.2019.pdf [In Polish: Regulations of Panek S.A. in the field of

car rental].

15. Service fees. Drive Now. Available at:

https://www.drive-now.com/gb/en/pricing/standard-fees.

16. Moffatt S., J. Fitzgerald. 2006. “The relationship between petrol

theft and petrol prices”. Crime and

Justice Bulletin: Contemporary Issues in Crime and Justice 101: 1-4.

Received 10.08.2020; accepted in revised form 29.10.2020

![]()

Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License