Article

citation information:

Ciuică, O., Dragomir, C.,

Pușcă, B. Safety culture model in military aviation organisation. Scientific Journal of Silesian University of

Technology. Series Transport. 2020, 108,

15-25. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2020.108.2.

Oliver CIUICĂ[1],

Cristian DRAGOMIR[2],

Bogdan PUȘCĂ[3]

SAFETY

CULTURE MODEL IN MILITARY AVIATION ORGANISATION

Summary. The list of organisational factors that may

constitute accident premises represents a good analysis instrument, equally

preventive, but also retrospective, in investigation situations. Forming an

effective safety culture is a vital element of acquiring and maintaining an

appropriate level of safety and implicitly limiting aviation events. The safety

culture “growth” process starts by successfully choosing the right

model for the organisation, evaluating the safety culture with the help of the

right tools and capitalising the results by taking improvement measures. Once

acquired, the safety culture gives the organisation an increased level of

security and confidence, thus: low accident rate, active involvement and responsibility

from all members, initiative in operations, safety procedures, direct and

effective feedback, careful and constant research of procedures, continuous and

intense training, setting performance standards both indoors and outdoors, planning

several scenarios to create the required variety, the desire to try new ideas,

accepting the risk, the failure.

Keywords: safety culture, leadership, aviation, Air

Force, military, training

1. INTRODUCTION

The essential

attribute of an organisation in the safety field is to issue regulations and to

monitor and control their compliance. The idea that regulations would be the

absolute solution for accident avoidance is widespread. Although they are

results of long experiences, some of them are “written with blood”;

regulations are not an absolute guarantee of safety. Admittedly, regulations

compliance has a big advantage: it represents an absolute parameter before the

law. For example: Does that mean I can

cross on green, even if I see a car coming, just because the law is on my side?

The fact that almost every accident

has a list of violations of the rules is not a justification for the hope that,

by absolute compliance with all regulations, the flight would be accident-free.

Arguments:

a) Like aeroplanes, regulations are also made by

people, so they are not perfect.

b) A regulation has a target (the field it is focused

at) but also consequences on some adjacent fields. Even the best regulations

can have unforeseen negative consequences. (Example: regulating the payment system of the air force staff).

c) If the rule does not fit the situation, then it is

not good just for the fact that it exists. If we could imagine a fully

regulated system, then man would have no role to play within it (it could be

replaced by an automatic machine).

d) Many regulations respond to the moment’s

need. After a while, they may no longer be effective. Delay in updating

regulations is one of the most dangerous sources of risk in aviation. People

have to face a changed situation based on old rules. This causes compromises (in order to make things work) or

blockages (not to conflict with the rules).

e) There are several levels of regulation, which are

not always concordant, and creates confusion and uncertain

“improvisations” (the law is

above an internal regulation).

f) At each hierarchical level, the pressure to comply

with the rules is higher from top to bottom than from horizontal and even less

from bottom to top. The mismatch between levels leads to normative practice

inconsistency, with high risks for operational safety. Failure to follow the

rules at a certain hierarchical level, when perceived or only suspected by

subordinates, has a devastating effect on the general normative climate. This

is, moreover, the essence of the mechanism of “authority

dissolution” (understanding by authority a space regulated by norms).

g) Finally, it would not be excluded that if someone

wanted to comply with maximum rigour to all existing regulations at any given

time, no plane could be lifted from the ground.

The sum of all

regulations defines an ideal professional space, as it can probably never be

found in real life. This is truer in critical situations (in war, in times of

economic crisis, transition, etc.). However, the arguments listed above are in

no way a rebellion against rules and regulations.

Aviation has been

and shall remain a highly normative institution. Most of the regulations are vital

to maintaining the efficiency and safety of the system. However, it has no use

to fetishise the compliance for norms, as a unique and absolute way of

preventing all problems. Sometimes, blind implementation of an inappropriate

rule can do more harm than ignoring it. However, we must keep in mind that

people are usually inclined to comply with regulations because this gives them

confidence and security (only some

categories of psychopaths violate the rules in principle just because they

exist). Therefore, even when a rule has been violated, there must be an

explanation, which as a rule has a much deeper meaning than just finding the

violation. When the analysis of an accident ends with the conclusion that

certain norms have not been observed, without going further in deciphering the

mechanism of this fact, we can say either that the investigation was not

professional or that it is trying to hide some deeper truths. Example of

“correct violation” of the rules and regulations: In case of loss

of power supply on-board, at night, under heavy weather conditions, the

regulation provides for “catapulting” of fighter jets equipped with

a catapult seat. Yet, this “rule” is usually violated, in all known

cases, the pilots succeeding in landing, usually with the damage of the

aircraft, but without other consequences. Moreover, the “violation”

has always been received positively, being highlighted by the driving factors.

In the end, however, the organisation shall have to resume this process

of forming its own safety culture, to determine the impact or better still if

the measures taken to improve the safety culture have had the desired impact or

if they need to be deepened. In the end, we shall conclude with a statement by

James Reason: “If you are convinced that the organisation you belong to

has a good/efficient safety culture, you are more than likely wrong ... a good

safety culture is something that you can tend to, but it's hard to get. Its

value and result lie more in the struggle to obtain it than in effect.” [4]

2. SAFETY MANAGEMENT

SYSTEM

Although

air accidents or catastrophes are rare, less serious events and a whole range

of incidents occur frequently. These negative manifestations of safety foresee

the imminence of a disaster with a strong impact on the resources of the

aeronautical organisation. Ignoring these indicators, with minimal influence on

safety only increases unwanted events.

In support

of diminishing security vulnerabilities, the International Civil Aeronautical

Organization (ICAO), imperatively supports the implementation of a Safety

Management System within all aeronautical organisations that sign the

convention. Thus, starting from 2006, the Safety Management Manual, a manual

that has the main role to outline this concept and not to present in detail the

steps to be taken for its implementation was introduced.

SMS

(Safety Management System) represents a well-defined process, centred at the

level of the entire organisation that generates effective, viable decisions

based on the potential risks identified during operations and services

provided.

SMS

promises lower loss rates, but safety culture is an essential condition for

success and the key to achieving future goals.

The main

pillar of aeronautical safety is the formation and development of a correct

culture and attitude in the aspect of the safety of the activities carried out

based on:

-

knowledge and discipline in compliance with the

regulations, operational procedures and the correct exploitation of the

technical means provided;

-

compliance with aeronautical safety rules in

carrying out activities;

-

encouraging free and honest reporting and

information of any potential factor or hazard that could affect the level of

aviation safety or which has generated events, including by distinguishing

between the occurrence of events due to unintentional errors and those causing

voluntary violations of normative acts in the field of aviation safety.

Through

education, training and action, staff must (re)know, identify and raise

awareness of acceptable and unacceptable actions/attitudes in military

aeronautical activities. Therefore, at all levels of the organisation, it

should be understood that in the case of situations considered unacceptable

(indiscipline, as an intentional action outside the limits of the normative

acts in force), the commanders can and must establish certain disciplinary or

administrative measures, proportional with the situation and the consequences

manifested and in accordance with the regulations in force.

The

systemic approach that encompasses all the actions carried out to improve the

aeronautical safety, as presented in the concept of safety management, brings

novelty elements by combining all the key elements that compete in carrying out

the activities in good conditions.

The key elements

of a Safety Management System are represented by:

-

the identification of hazards – recognition

method of distinct vulnerabilities

of each organisation;

-

reporting of events that occurred - process of data

acquisition and preparation of statistics on safety indicators (incidents,

accidents, recurrence of events, etc.), but also voluntary reporting of

“minor” incidents with a negative effect on safety;

-

risk management - standard approach for assessing

risks and vulnerabilities for controlling and eliminating them;

-

measuring performance in terms of meeting the

objectives - management tool for analysing the safety objectives imposed within

the organisation;

-

safety quality assurance (auditing) - process based

on the quality of managerial principles that support the improvement of the organisation’s

performance to maintain the required safety standard.

3. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION

One of the

most important and applied models in the aviation community for determining

causes that lead to the occurrence of aviation events is one proposed and

developed by Professor James Reason[5], which

can be found in speciality literature as the “Reason Model” or the

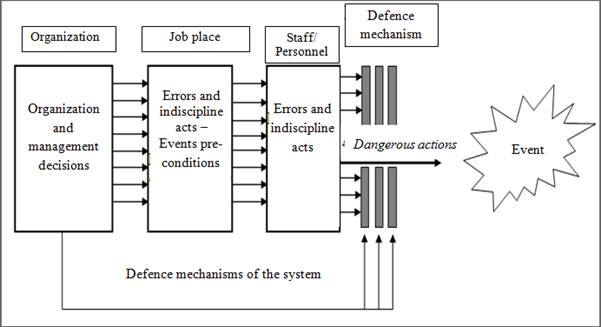

“Swiss Chees” Model (cheese). This model (Fig. 1) describes the

causality of events as a chain of successive failures of the security defence

system and the successive activation/manifestation of latent factors that have

adverse effects on the performance of the mission (equipment failures, organisational

factors, errors, procedural violations, weather phenomena/conditions,

deficiencies of regulations, deficiencies in training/evaluation, etc.).

Rarely, a single failure in this defensive chain can lead to the

production of an event or its severe effects. The Air Force aeronautical system

is based on the generation of defensive elements for any of its components.

Interrupting the defensive chain can be prevented by including decision making

at different levels of the organisation.

In certain situations, the interruption of the defence may be caused by a

combination of active failures or latent conditions that, according to the

Reason model, can be chronologically successive until the generation of a

dangerous situation or even the production of aviation events with serious

effects.

Active failures are actions or inactions that usually have an immediate

aggravating effect. This category includes errors and violations of normative

acts. These are attributed to the staff who actually carry out aeronautical

activities (pilots, crew members, technical-engineering staff, traffic

controllers, etc.) and the effect can be severe.

Fig. 1. Causal model of accidents

Latent conditions exist in the system before an event occurs. They have

the following particularities:

-

they do not produce

consequences as they are inactive, as a result, they are often difficult to

perceive and identify, and risks are rarely associated with them;

-

there is a long period of

time from occurrence to manifestation;

-

in most cases they are

generated by people;

-

they are highlighted when

the defensive means fail in aviation safety (occurrence of events).

These latent conditions can be generated by:

-

weak aeronautical safety

culture;

-

equipment/material with

deficiencies, which have been designed, manufactured or exploited improperly;

-

conflicting objectives or

states in the organisation;

-

erroneous decisions;

-

organisation malfunctions.

The Reason model is thus constituted as a model of the “organisational”

aviation events, bringing the human factor to the centre of attention of

aeronautical events investigation by identifying its interaction:

-

at the individual level (the

role of the person who leads and the one who enforces) and

-

collectively (the role of

the organisation), both by the organisation way and the decision making.

Similarly, the model presents a series of elements regarding both the

causality and ways of preventing the events, highlighting the following:

-

people make mistakes and it

is important that these errors are made known, especially by the crews during

the flight, and is important that there is time, space, resources and ways to

prevent, mitigate or cancel the effects;

-

the aeronautical system has

defensive means that can compensate for the fluctuation of human performance or

the quality of decisions;

-

the system can generate

latent conditions that can be activated in certain situations or under the

influence of certain factors.

By analysing in detail, the causality of the accidents proposed by this

model, we identify a mechanism of correlation with the processes that are

carried out at the level of the organisations, which by identifying the process

progression during the activities, determine both the logic of the occurrence

of the aviation events and the modalities of prevention (the defensive layers

of the model) that the aeronautical system can have available in different

phases.

A particular path is represented by the generation and then the

manifestation of latent conditions. They may be represented, in addition to

those deficiencies in design and construction of equipment and incomplete or

inadequate standard operating procedures, or deficiencies in staff selection

and training. Thus, we can identify two major components that can generate

latent conditions:

-

deficiencies in identifying

the dangers/threats as well as ways to reduce the risks associated with them;

these threats remain in the system and can be activated by factors or

operational conditions in a particular situation;

-

normalisation of situations

considered as an exception to the rule regarding, in particular, the allocation

of resources. This situation forces the system to adapt so as to continue the

execution of the assigned missions until the critical limit is reached or

exceeded (exceptions are established that become rules and this process risks

becoming a habit as the resources are continually maintained or reduced).

The latent conditions limit the defence capacity of the aeronautical

system against threats/dangers, especially of the crews who carry out missions

in flight and increase the risk of producing events by also restricting the

possible solutions to prevent and correct errors of any kind:

-

the level of training,

experience and continuity of the training are limited, affecting the

maintenance, acquisition or improvement of flying skills;

-

decision-making and application

skills are affected (increases the time, space and resources required,

decreases the quality in their application);

-

the performance,

characteristics and operating particularities of aircraft and technical systems

remain in line with the requirements for mission execution and offer limited

possibilities to prevent dangerous situations or limit their severity;

-

changes to normative acts,

assigning new missions or increasing their complexity are more difficult to

control in order to identify specific dangers or safety measures;

-

the frequent changes of

structure or classification, the lack of qualified or experienced staff in the

field generated by resources or by bad management of staff lead to difficulties

in the sense of identifying specific threats or efficient and effective

security measures.

The training and experience in aeronautical activities, the provisions of

the normative acts and the technology are means that finally offer the

possibilities of error prevention and equally the main tools for the enforcement

of the missions in suitable conditions of performance, as well as efficiency

and effectiveness.

A second path is represented by the working conditions, as follows:

-

personal factors: stability

at the workplace, qualification and experience, moral and atmosphere within the

organisation or within the crew, the attitude of the management, the

remuneration;

-

environmental factors at

work: ergonomics, lighting, temperature, cabin pressure, vibration and last but

not the least, the associated occupational diseases.

Poor working conditions directly influence human performance during

activities, being of major importance to the crews in flight, especially

through their contribution to the manifestation of errors and voluntary

violation of procedures or regulations. The difference between error and

violation of rules is motivational and intentional.

From the viewpoint of prevention, the aeronautical safety activities

should allow the intervention on the two paths presented above, thus:

-

supervises, analyses and

evaluates the processes carried out at the level of organisations (internally and

hierarchically: respectively of the Air Force base of the General Staff of the

Air Force and of the Flight Group and of the squads from the Air Force base

level), identifying in real and objective terms, the latent conditions and

regenerating/strengthening defensive instruments;

-

supervises, analyses and

evaluates the working conditions for identifying those factors that affect

their performance and generates actions that will develop better working

conditions and tools for avoiding errors, limiting or correcting their effects;

-

develops specific risk

management processes for identifying security threats as well as identifying

and applying risk reduction or elimination measures.

4. REPORTING EVENTS

The safety management system involves the reactive and proactive

identification of the dangers manifested to safety during aeronautical

activities. It is fully accepted that accidents or catastrophic investigations

are much more detailed and thorough in research compared to investigations on-premises

or incidents. Thus, when the safety optimisation measures are taken only

following the conclusions of the investigations on accidents and disasters, the

scenarios underlying them are limited. This way, wrong conclusions regarding

the level of safety can be drawn, and moreover, inadequate corrective actions

can be established.

The statistics show that the number of premises and incidents is much

higher compared to the number of accidents and disasters (Classification of

aviation events in the Romanian Air Force according to Annex no. 13). The

causes and contributing factors associated with the premises or incidents can

escalate into accidents or disasters. Often, only luck causes a minor event not

to turn into a disaster. Unfortunately, these minor events are not always known

by those in charge of implementing risk reduction and elimination measures.

This may be due to the lack of a reporting system or the lack of motivation of

the staff in not reporting the events or dangers discovered.

The lessons learned, the conclusions drawn from the incidents offer

important scenarios for analysing and avoiding future events during activities.

Therefore, there is a need for a database that provides the nature, cause and

remediation of unwanted situations.

Equally valuable, such as information on the production of events, are

information on unsafe, dangerous conditions that are yet to cause any incident.

The information on reported incidents facilitates the discovery of the

risks associated with them, helps to implement intervention strategies and

provides feedback regarding the evaluation of the effectiveness of the

intervention. Events with minimal impact on safety also provide a first-hand

understanding of the actions taken at the incident site regarding the

conditions and actors involved. They can provide important details regarding

the relationship between existing stimuli and their actions during the event,

reactions that can affect their performance based on multiple factors such as

fatigue, interpersonal interactions or distraction. Moreover, the members of

the organisation involved in conducting events can offer solutions to increase

the level of safety depending on the type of events. Data on-premises and

incidents, even accidents, can be used to improve operating procedures, control

the design of the technique used, and provide a better perspective on human

performance in aircraft operation, air traffic control or technical service of

the aerodrome.

Civil aviation regulations [6] propose three types of reporting systems:

1.

Mandatory reporting system -

requires the persons responsible for reporting the events (or those involved in

the event) to report on a hierarchical scale that a particular event has

occurred. For this, a regulation that stipulates who shall report, to whom

shall report and what should be reported[7] is needed. Although, such regulations may not cover all types of events

to be reported given the large number of operational variants, the basic rule

in informing about their production should be: “Report if you are unsure

about reporting”.

2.

Voluntary reporting system -

involves the reporting on the initiative of any member of the organisation of

an event or of any inappropriate behaviour that endangers future activities.

Mandatory reporting involves informing about

the events produced with the equipment provided (the hardware part of the organisation),

with the need to collect data regarding the technical failures and its

implications. To prevent these unwanted events, we propose the introduction of the

voluntary reporting system meant to provide more information on the role of the

human factor in the production and development of aviation events.

A good example of a voluntary reporting system

is the US Aviation Safety Action Program (ASAP)[8]. Designed to increase aviation safety by preventing accidents and

incidents, this is a system that protects the identity of the person reporting,

it was created based on a model used by many airlines. This program, based on

the transmission of network information, encourages the voluntary reporting of

safety problems during the operation or maintenance of the technique, critical

safety information, which might otherwise remain unknown.

The program is specially designed to detect the dangers and errors

observed by crews, technical staff or air traffic controllers and their

dissemination throughout the organisation so that everyone can have access to

safety information. It additionally gives the organisation management examples

of risk that might otherwise be “invisible” so those risk

management decisions can increase the security of operations.

The challenge in implementing this reporting system is represented by the

lack of punitive actions against those who subscribe to the information about

the security threats. Being a non-punitive system, it will encourage the

reporting of this much-needed data in the process of increasing the safety

level.

3.

Confidential reporting

system - aims to protect the identity of the information provider. Confidential

reporting is not stored in a database or recorded. Usually, it is verbal

information, mainly about the errors produced by the human factor in the

activities of the organisation. This should be initiated without fear of

reprisals or embarrassment, the main purpose of the information is to learn

from the mistakes of others.

It is understandable that man is reluctant to

report his own mistakes. Many times, following an aviation event, the

commissions of investigation find that many of those present in the organisation

were aware and knew the latent conditions of the event production before it

happened. The non-reporting of perceived threats can be due to several reasons:

embarrassment feeling before the interlocutor, self-accusation (if they were

the ones generating the risk conditions), reprisals or sanctions from the

hierarchy.

For a reporting system to be valid, the organisation

must avoid reasons safety issues are not shared.

Trust and avoidance of sanctions are the basic

principles in promoting a positive safety culture.

Persons reporting incidents, behaviours or

errors that impact on the safety of their activities should be convinced that

the organisation (management of the organisation) will not use the information

received against them in any way or for any reason. Without this certainty,

staff will avoid reporting errors or other observed hazards.

A positive safety culture within the organisation

will generate the level of confidence required in reporting the observed

inconsistencies. Specifically, the organisation must have a good tolerance for

errors inherent in human activity of any kind, and the reporting system should

be perceived as being correct in terms of its handling of errors (unintended

errors). One must not misunderstand that in this way deliberate acts of

violation of the regulations will remain unpunished. This is an example of just

culture, an integral part of the safety culture.

To avoid anonymous reporting, which may leave

interpretations in the information transmitted, and may have other purposes

other than those related to security, the reporting system must be

non-sanctioning, non-punitive and be based on confidentiality.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Recommendations

on aviation safety:

-

analyse all

aviation events that occur in your unit and other units to identify

malfunctions that may lead to other aviation incidents or accidents;

-

approach

rationally and functionally, the decision-making process for flight, starting

from the interactions between human, technical or environmental factors that

can ultimately lead to the occurrence of aviation events;

-

uniformly

distribute effort according to the stage of training objectives and tasks to

eliminate overwork at work, inadequate perception of danger or motivational

dysfunctions;

-

identify the

social factors that impact on in-flight training:

▪ social problems;

▪ financial problems;

▪ family relationships;

▪ relationships within the

group;

-

eliminate tensions

within the system and harmonise the activity of the compartments based on the

idea that pilots, technical staff, insurance staff and navigators are the main

preventers of aviation events.

During fight missions, mission

accomplishment becomes paramount to all other considerations. No state,

throughout history, has allowed the resources available for the accomplishment

of the mission to be diminished by facts that are not attributed to the actions

of the opponent. The accidents, beyond the costs they incur, reduce the

operational capacity and, implicitly, the successful accomplishment of the

assigned missions and create an image crisis of the Air Force, the most

important category of an army.

Aknowledgement

This work was supported by a grant of the Ministry of National Education and Romanian Space Agency, RDI Programe for Space Technology and Advanced Research - STAR, project number 174/20.07.2017.

References

1.

Prentiss

L., B.J. Brownfield. ”Aeronautical Decision Making”.

Available at:

http://www.avhf.com/html/Library/Aeronautical_Decision_Making.ppt.

2.

AFI91-204

12 FEB 2014 - Air Force Instruction ,

Department of the Air Force Headquarters Air Force Safety Center, Washington,

2016.

3.

AOPA. Available at:

http://flighttraining.aopa.org/magazine/1999/September/199909_Features_Hazardous_Attitudes.html.

4.

Reason J. 1997. Managing the

Risks of Organizational Accident. Ashgate, England: Aldershot.

5.

Reason J. 1990. Human Error, Cambridge. University Press, New York.

6.

Williamson A., A. Feyer, D. Cairns, D. Biancotti. 1997. „The

development of a measure of safety climate: the role of safety perceptions and

attitudes”. Safety Science 25.

7.

JAR-OPS 1 Subpart N Section 2 AMC OPS 1.943/1.945(a)(9)/1.965(b)

(6)/1.965(e) - Crew Resource Management (CRM).

8.

CANSO The Civil Air Navigation Services

Organization. Safety Culture Definition and Enhancement Process. 11April 2013.

9.

ICAO Doc 9856. „Safety Management Manual”. 2006.

10. Instructions

on the technical investigation of aviation events produced with military

aircraft. Bucharestt, General Staff of the Air Force. 2007.

11.

Air Force Safety Center. Available

at: http://www.afsec.af.mil/proactiveaviationsafety/asap/index.asp.

Received 20.02.2020; accepted in revised form 30.05.2020

![]()

Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License