Article

citation information:

Mindur, M. Significance of the port of

Singapore against the country’s economic growth. Scientific Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series

Transport. 2020, 106, 107-121.

ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2020.106.9.

Maciej MINDUR[1]

SIGNIFICANCE

OF THE PORT OF SINGAPORE AGAINST THE COUNTRY’S ECONOMIC GROWTH

Summary. The economy of Singapore is characterised by a

stable political environment, favourable business conditions and very well-developed

infrastructure attracting foreign direct investment, being the driving force of

the economy. It is highly dependent on export, as well as on the dynamic

sectors of transport, business and financial services. Singapore’s

natural deep-sea ports and the geographical location at the crossroads of

important shipping channels makes its trade a major economic sector, next to

production and services. There are currently more than 5,000 maritime companies

operating in Singapore, including over 130 international shipping groups, which

constitute an important pillar for the international maritime transport hub.

This article discusses Singapore’s economic situation by analysing the

dynamic GDP growth over the years 1960–2016 as well as other economic

indicators achieved in 2004–2017, including the dynamics of foreign

trade. This research covers the port’s ownership and organisational

structure, and its terminals have been reviewed in terms of their location,

infrastructure and functions by taking into account the new generation terminal

of the port of Tuas, currently under development. Over the years, the port has

seen a steady increase in revenue from transhipment, which is confirmed by the

dynamics of the container volume growth over the years 1972–2017, the

transhipment volume over the years 2007–2018 and the number of container

ships calling at the port along with their total capacity over the years

2007–2017, as elaborated in the article.

Keywords: port of Singapore,

economy, terminals, transhipment

1. INTRODUCTION

The

Singapore seaport is the busiest transhipment hub in the world. Located at the

southern end of the Malay Peninsula, 30 km southwest of the port of Johor in

Malaysia, it provides connectivity to more than 600 ports in 123 countries.[2] The island nature of the

city-state of Singapore (besides the main island of Singapore, it contains 60

small coastal islands) determines the dynamic development and excellent

maintenance of both linear and point infrastructure of transport, and maritime

transport in particular.

Fig. 1. Geographical

location of Singapore

Source: https://www.google.pl/maps/place/Singapur/data=!4m2!3m1!1s0x31da11238a8b9375:0x887869cf52abf5c4?sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwil_ZGf7qHhAhUj_SoKHYzdA0sQ8gEwAHoECAkQAQ

For centuries, Singapore

performed the important role of a transhipment hub for regional and

international trade as the economic capital of the Malay Peninsula. However,

once Singapore gained full independence in 1965 (in 1963, following its merger

with Malaysia, it ceased to be a part of the British Empire), the port was

forced to compete with others in the region. Along with its progressing

revival, the economy was being oriented towards obtaining raw or semi-processed

products from regional and global markets as well as exporting the processed

products back to these markets.[3]

In the late 1960s, a

decision was made to build a container terminal in East Lagoon (today’s

Tanjong Pagar) in the port of Singapore, being the first in Southeast Asia,

even though container ships were not yet widespread means of freight transport

at that time. As the transport of containerised cargo developed and the volume

of bulk cargo increased, the port’s facilities have been successively

expanded since the 1980s in order to increase its capacity. In terms of the number

of transshipped containers counted in TEU, Singapore is only second to Shanghai

among the world’s largest ports (with 36.6 million TEU transshipped in

2018; Shanghai’s volume being 40.2 million TEU).

The transformation of a

small regional port into one of the busiest ports in the world has undoubtedly

been determined not only by its favourable geographical location at the

crossroads of important trade routes but also by the courageous and visionary

plan to build the first container terminal.

2. ECONOMY OF SINGAPORE

In only a few decades, Singapore has advanced from a

poor post-colonial region to the rank of the largest Southeast Asian centre of

business, commerce and finance with highly developed and successful free-market

economy. The city primarily owes its high level of development to the highly

advanced industrial production based on the latest technologies.

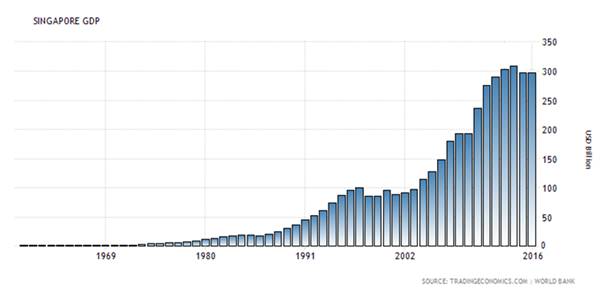

Fig. 2. Trends in the GDP of

Singapore over the years 1960–2016

Fig. 2. Trends in the GDP of

Singapore over the years 1960–2016

Source:

https://tradingeconomics.com/singapore

The economy of Singapore is characterised by a stable

political environment, favourable business conditions and very well-developed

infrastructure attracting foreign direct investment, being the driving force of

the economy. The Doing Business 2018 ranking on the ease of doing business

ranks Singapore second among 43 countries of the Asia-Pacific region. The

service sector generates nearly 70% of the GDP, while the industry and the

construction – more than 30%. The maritime industry accounts for 7% of

the GDP and employs more than 170,000 people. The agricultural sector does not

contribute significantly to the GDP. It is for the lack of arable land that in

terms of employment the agriculture accounts for a mere 1.3% of the total

labour force.

Tab. 1

Indicators of Singapore’s economy

for the years 2004–2017 (in per cent)

|

|

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

|

GDP |

13.7 |

8.1 |

8.8 |

12.1 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

15.2 |

5.4 |

3.4 |

4.4 |

2.9 |

2.0 |

2.4 |

3.6 |

|

Private consumption |

5.1 |

4.3 |

6.2 |

10.5 |

8.5 |

0.2 |

9.8 |

8.1 |

6.8 |

4.3 |

2.8 |

3.7 |

4.1 |

3.9 |

|

Unemployment rate (%) |

3.4 |

3.1 |

2.7 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

3.0 |

2.2 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

1.9 |

2.0 |

1.9 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

|

Inflation rate |

1.7 |

0.5 |

1.0 |

2.1 |

6.6 |

0.6 |

2.8 |

5.2 |

3.6 |

2.4 |

1.0 |

-0.6 |

-0.5 |

0.6 |

|

Export |

20.5 |

14.0 |

12.8 |

4.4 |

5.8 |

-18.0 |

22.4 |

7.5 |

4.2 |

8.0 |

3.6 |

-6.8 |

-3.1 |

10.3 |

|

Import |

23.6 |

13.6 |

13.7 |

4.5 |

13.9 |

-21.0 |

18.8 |

8.6 |

5.9 |

9.8 |

1.2 |

-11.1 |

-4.9 |

12.1 |

|

Total investment |

12.5 |

-9.2 |

12.4 |

-15.3 |

16.9 |

-39.3 |

103.1 |

29.6 |

1.0 |

19.8 |

3.6 |

5.4 |

-15.6 |

14.1 |

Source: Ministry of Trade and Industry, Singapore; https://www.mti.gov.sg/

In 2017, Singapore’s GDP increased by 3.6% compared

to 2016 and was twice as high as forecasted. The greatest impact on such

results of the Singaporean economy, being particularly sensitive to global

economic fluctuations, was exerted by the increased global demand for

electronic products, which was also one of the most important growth drivers in

2018.

Singapore’s unemployment rate is very low, as it ranged between 2.1

and 3.4% in the years 2004–2009, however, it has remained at a fixed

level of ca. 2% since 2010.

Immediately after the

global financial crisis, Singapore was struggling with high inflation exceeding

5% in 2011. However, this record-breaking level was drastically reduced to 0.6%

in 2017.

The Singaporean economy is highly dependent on

exports, especially of electronics, petroleum products, chemicals, medical and

optical equipment, pharmaceuticals, as well as dynamic sectors of transport,

business and financial services.[4]

In 2017, following two consecutive years of decline, Singapore’s

foreign trade regained its typical dynamics, as the trade volume increased by

11.1%, the imports grew by 12.1% and the exports by 10.3%. The aforementioned trade revival

was mainly driven by an increase in the trade of electronics. Singapore’s

main import partners are China (14.2%), Malaysia (11.2%), the European Union

(10.2%), the USA (8.3%) and Hong Kong (7.2%), while the most important export

markets are China (14.5%), Hong Kong (12.3%), Malaysia (10.6%), the EU (8.4%)

and Indonesia (7.5%).

The dynamic development

of international trade in commodities is by no means limited by

Singapore’s lack of natural resources or shortage of land. Its natural

deep-sea ports and geographical location at the crossroads of important

shipping channels make its trade a major economic sector, next to production and

services.[5] There are currently more than 5,000 maritime companies operating in

Singapore, including over 130 international shipping groups, which constitute

an important pillar for the international maritime transport hub.[6]

3.

OWNERSHIP STRUCTURE VS PORT MANAGEMENT

The port of Singapore is

administered and supervised by the state, in terms of both financing and

development. It is managed by a government agency, the Maritime and Port

Authority of Singapore (MPA), established in 1996 by the merger of the Marine

Department, the National Maritime Board and the regulatory departments of the

former Port of Singapore Authority (PSA), which was transformed into a holding

company in 2004.

The MPA operates on

behalf of the state government in the areas of maritime transport as well as

port management, development and promotion. Some of its tasks are as follows:

-

collaboration

with the government and maritime partners to ensure that the port develops on a

continuous basis and strengthens its position in the global market,

-

supervision

of the marine traffic, safety and the navigation system, coordination of

terminals, implementation of measures to reduce the negative environmental

impact of shipping,

-

undertaking initiatives to encourage major ship-owners and operators to

commence operations in Singapore,

-

representing

the interests of the Singaporean maritime transport sector abroad[7].

The port operations

performed in both general cargo (container and conventional) and ro-ro

terminals are handled by two port groups: PSA Singapore (established by way of

transformation of the Port of Singapore Authority) and Jurong Port. Both groups

belong to Temasek Holdings, owned by the state treasury and providing funding

for the port’s continuous development. Temasek Holding also controls a

significant number of other companies operating in Singapore, including the DBS

bank (the Development Bank of Singapore Limited) and Singapore Airlines.[8]

The bulk cargo terminals

are predominantly managed directly by their users, such as refineries, chemical

industry companies, etc. (companies such as LANXESS, BASF, BP, SHELL or EXONN

MOBIL run their plants in Singapore).

4. PORT ORGANISATION AND

INFRASTRUCTURE

There

are two main port groups functioning in Singapore: PSA Corporation Limited,

with its subsidiary company, PSA Singapore, primarily responsible for container

transhipment, and Port Jurong, handling general, bulk and container cargo. Both

ports are suitable for all types of vessels. Container handling services are the

port’s key activity, with approximately 85% of the containers arriving in

Singapore being transshipped onto vessels bound for another port of call. The

handling capacity of the port of Singapore is 50 million TEU per year.

Fig. 3. Arrangement of

ports and their respective terminals in the port of Singapore

Source: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/full-steam-ahead-for-new-tuas-mega-port

5. PSA SINGAPORE

PSA Singapore currently offers 67 quay berths at its

container terminals in Tanjong Pagar, Keppel, Brani and Pasir Panjang, being

operated as a single and undivided integrated facility. In 2018, PSA Singapore

handled 36.31 million TEU of containers. This transhipment hub accounts for

nearly one-seventh of the total container transhipment capacity worldwide and

for more than 4% of the global container handling capacity.

There is one of the world’s largest warehouse

parks on the premises of PSA Singapore, offering more than 12,000 refrigeration

units (more than 1.3 million TEU of refrigerated containers were handled there

in 2016). The integrated refrigeration monitoring system (iRMS) is linked to

the CITOS® system, which enables cargo to be tracked on a real-time and

online basis at every stage of operation. It allows customers to monitor the

condition of their cold stores wherever they actually are in the world by means

of PSA Portnet® via the internet. The Reefer Maintenance & Repairs

(RMNR) system, on the other hand, keeps track of all failures, enabling quick

response whenever refrigeration units require repairs, as they may contain

sensitive and valuable cargo.

PSA Singapore handles more than 0.5 million TEU of

dangerous goods per annum. Some of the services rendered in this scope include

processing of dangerous goods (DG), leakage/damage control to ensure safe

shipment, labelling for containers with missing mandatory warning labels or

ones that do not conform with the IMDG codes, as well as handling and storage

of highly dangerous goods for local delivery or onward shipment. At the same

time, PSA supplies full sets of spare parts for each refrigerated container

type. Moreover, a full range of standard storage warehousing is available at

docking stations for empty containers. PSA operates as the main transhipment

hub for collecting empty containers from ships or for sending them out.[9]

The flagship PSA Singapore terminal is Pasir Panjang,

featuring the most technologically advanced transhipment machinery and

equipment. The terminal is currently used for testing a fully automated

electric crane system, 30 automatic-control vehicles, eight hybrid and 22

battery-powered electric vehicles.[10] It is expected that the

solutions tested at Pasir Panjang will be implemented at Singapore’s Tuas

mega port, currently under construction, which is described below.

In the second half of

2016, the transport group of CMA CGM-PSA Lion Terminal Pte. Ltd. (CPLT),

established by CMA CGM S.A. (CMA CGM) and PSA Singapore Terminals Pte. Ltd.

(PSA), commenced its operations in Pasir Panjang. The company has four berths

for mega container ships at its disposal on the premises of Pasir Panjang

Terminal (PPT), which has been extended under phases 3 and 4 (Fig. 3). CPLT

uses the most highly advanced port infrastructure and the latest technologies,

and they also provide long-term terminal services for CMA CGM and its shipping

service divisions.

Another joint venture

operating in the port, namely COSCO-PSA Terminal Pte Ltd (CPT), was established

by COSCO Shipping Ports Limited (CSP) and PSA. Founded in 2003, CPT was

functioning as the main container transport hub in the region until 2017 when

it moved from the formerly managed two-berth terminal to one with three

mega-ship berths completed under phases 5 and 6 of the expansion. In November

2018, CSP and PSA signed an agreement on the commissioning of two new berths

and rendering them available to the company. This means that CTP will control

five berths in total, which will increase its annual handling capacity from 3

to approximately 5 million TEU. The new mega-ship berths, similar to the

existing ones, will be supported by the shipyard’s highly automated

technology.

In March 2006, MSC-PSA Asia Terminal (MPAT) was officially opened as a

joint venture between the world’s second largest shipping line, the

Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) and PSA International. The berths owned by

MPAT are fully integrated with other berths in Pasir Panjang. MPAT is capable

of handling mega-ships with a capacity exceeding 14,000 TEU.

The Pacific International Lines (PIL) dedicated container terminal is

located in Keppel. The joint management and operation of the terminal for PIL

and PSA Singapore (PSA) is performed by the joint venture company PIL-PSA

Singapore Terminal Pte Ltd (PPST). Both the terminal and the berths in Keppel

are fully integrated with other facilities operated by PSA.

The first Singaporean terminal dedicated to cars, that is, the Asia

Automobile Terminal (Singapore) (AATS), was launched in January 2009. It is a

joint venture of PSA, Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha (NYK) and Kawasaki Kisen

Kaisha Ltd (K Line).

Next to

the terminals managed by joint ventures in Pasir Panjang, there are also

multifunctional terminals. These are Pasir Panjang Automobile Terminal (PPAT),

which commenced its operations in January 2009, and the multi-purpose terminal

of Sembawang Wharves. PPAT is a ro-ro vessel transhipment hub, featuring three

separate quay berths. The unroofed car parking yard and the multi-storey car

park provide a total of approximately 20,000 parking spaces. The multi-purpose

Sembawang Wharves terminal handles general and speciality cargo, including

heavy equipment, steel products and cables. There are numerous storage

facilities, including open ones, at the Sembawang wharf for long and short-term

rental.

6. TUAS PORT

Like many other ports around the world, the port of

Singapore has developed into a city, which used to serve as a focal point for

trade and cargo shipping operations in the past. The lease of three terminals

originally sited on municipal territories, that is, Tanjong Pagar, Keppel and

Brani, expires in 2027. The Singaporean authorities have decided to revitalise

the vacant areas as a part of the Greater Southern Waterfront project assuming

that a quayside district with futuristic residential buildings, entertainment,

recreation and tourist attractions will be built in this place, providing

access to numerous green areas and the sea itself.[11]

The relocation of port facilities as

well as the personnel from the Tanjong Pagar, Keppel and Brani terminals to

newer facilities with deeper basins in Pasir Panjang, to be operated by PSA for

at least another 20 years, began in 2016. The target is to move all operations

to a new generation terminal on a new artificial peninsula, known as the port

of Tuas, which is due to be completed in 2040 (phase 1 is scheduled for

completion in December 2020, with the port to be gradually commissioned

starting from 2021).[12] The PSA Singapore

container terminals will eventually be consolidated in a single location.[13] The new port of Tuas will be

capable of handling the largest container ships in the world, and it will

become the world’s largest automated container terminal with an annual

capacity of 65 million TEU.[14] It is, by all

means, an adequate location due to its sheltered deep waters and the proximity

to both international shipping routes as well as major industrial areas in the

western part of Singapore. The decision-makers responsible for the port

construction and development intend to make the port of Tuas a part of a larger

ecosystem integrating various stakeholders in a logistic community, both

digitally and physically, and to enable deployment of integrated intermodal

supply chain solutions that will result in more reliable and faster delivery of

goods to their destinations.

The new port will feature such infrastructure as automated

quay cranes and automatic-control vehicles. New systems are to be deployed to

enable synchronised negotiating between all port facilities. The future

dispatch centre will combine the functions of control and coordination of the

terminals, ensuring the organisation of all automated port operations and

maintenance. It will be capable of remotely servicing and diagnosing the

equipment.

7. JURONG PORT

The port of Jurong was

commissioned in 1965 to function as a port for handling of bulk and general

cargo, intended to meet the needs of the industrial development of

Singapore’s Jurong district. Its main terminal located in Singapore

currently receives more than 15,000 vessels per year, both from the region and

from abroad.[15]

Jurong

Port hosts the world’s largest cement terminal serving more than 90% of

Singapore’s bulk cement imports. The annual handling capacity of a

terminal arranged on a 5.3 ha plot of land exceeds 7.5 million MT. The terminal

features a state-of-the-art infrastructure and equipment to ensure safe,

efficient and environmentally friendly cement discharge. Cement terminals 1 and

2 are situated at deep-water quay berths of up to 12.9 m in length, and they

can accommodate ships with a capacity of up to 50,000 DWT. They feature 5 screw

unloading machines, and their closed-loop air transport system enables cement

to flow freely into storage silos.

Steel Terminal is specialised in handling all kinds of

steel products (sheets, wire coils, reinforcing bars, pipes, beams, rollers,

etc.). The terminal offers storage yards and warehouses with an area of 484

thousand m2 and can handle vessels of 15.5 m in draught.[16]

Owing to its excellent connectivity

solutions and excellent modern port infrastructure, Jurong Port Combi Terminal

provides for transhipment of different types of containers and general cargo on

multipurpose vessels.

Fig. 4. Visualisation of the Tuas mega port

Source: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/spore-plans-to-keep-port-attractive

There is a project being implemented at Jurong Port to

build Jurong Tank Terminal, a state-of-the-art liquid bulk cargo handling

terminal equipped with 19 tanks for storage and handling of clean petroleum

products and chemicals. With the estimated value of 140 million USD, the

project is a joint venture of Jurong Port Singapore Holding and Oiltanking

Investment Holdings. The new terminal, sited on 16 hectares of land, is facing

the Jurong Island petrochemical centre in Singapore, both to be connected by

pipelines. It will have quay berths capable of accommodating vessels of 16 m in

draught and up to 120,000 tonnes in deadweight. The terminal’s initial

capacity will come to ca. 232,000 m3, while after phase 2 of the

project is completed, it will potentially rise to 470,000 m3.

There are two terminals in Jurong Port, which play a

key role in the domestic ship supply sector, namely, Penjuru Lighter Terminal

intended to service lighter ships, and Marina South Wharves used to supply

ships with spare parts and food. These terminals handle a total of 800,000 MT

of cargo per year. They provide quay services, berth and ancillary services.

8.

PORT’S TRANSHIPMENT SERVICES

The port of Singapore is a

multi-purpose port with an area of 752 ha and a quay length of 21,630 m,

handling transhipment of general cargo (containerised and conventional), bulk

cargo (liquid and dry) as well as ro-ro vehicles. The port is capable of

handling 1,000 ships entering or leaving the port per day in 10-minute

intervals.[17]

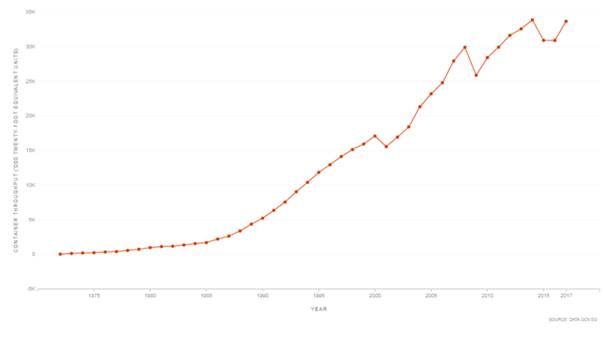

Over

the years, the port has seen a steady increase in revenue from transhipment. In 2018, the volume of

container transhipment increased from 33.7 to 36.6 million TEU, that is, by

7.2% compared to the previous year. The dynamics of the container volume growth

is shown in Fig. 5.

As the

world’s demand for goods transported by sea increases, shipowners are

using larger and larger container ships capable of carrying enormous quantities

of cargo in order to reduce shipping costs. Due to meticulous planning and

continuous improvement of its infrastructure, Singapore has become one of the

few ports in the world that can serve the largest vessels.

Tab. 2

Number of container ship

arrivals at the port of Singapore over the years 2007-2017

|

Year |

Container ship

arrivals |

Number of

transhipments (‘000 TEU) |

|

2007 |

19,946 |

27,935.5 |

|

2008 |

20,589 |

29,918.2 |

|

2009 |

18,005 |

25,866.6 |

|

2010 |

18,967 |

28,431.1 |

|

2011 |

19,290 |

29,937.7 |

|

2012 |

18,567 |

31,649.4 |

|

2013 |

17,798 |

32,578.7 |

|

2014 |

17,219 |

33,869.3 |

|

2015 |

17,722 |

30,922.3 |

|

2016 |

17,932 |

30,903.6 |

|

2017 |

17,663 |

33,666.6 |

Source: author’s own materials

based on

https://www.mpa.gov.sg/web/portal/home/maritime-singapore/port-statistics.

Fig. 5.

Volume of container transhipment in the port of Singapore over the years 1972–2017 in million TEU

Source:

https://data.gov.sg/dataset/container-throughput-annual?view_id=ebe25612-f598-422e-9326-fd7dbc4c6ae0&resource_id=dcf81859-2a92-4ff6-a499-5356a0b82011

The volume of

transhipments handled over the years 2007–2018, in a breakdown into

general cargo (including containerised and conventional) and bulk cargo has been

summarised in Table 3.

Tab. 3

Volume of container

transhipment in the port of Singapore over the years 1972-2017 according to the

type of cargo in ‘000 tonnes

|

Year |

General cargo |

Bulk cargo |

Total |

||

|

containerised |

conventional |

liquid |

dry |

||

|

2007 |

289,094.2 |

25,823.2 |

157,382.3 |

11,316.4 |

483,616.1 |

|

2008 |

308,489.7 |

27,934.9 |

167,318.9 |

11,671.8 |

515,415.3 |

|

2009 |

262,896.8 |

17,452.1 |

177,323.7 |

14,627.2 |

472,300.3 |

|

2010 |

289,693.5 |

23,989.7 |

177,070.2 |

12588.7 |

503,342.1 |

|

2011 |

309,379.9 |

26,130.6 |

183,843.3 |

11,821.8 |

531,175.6 |

|

2012 |

323,714.0 |

29,827.6 |

169,671.5 |

14,799.0 |

538,012.1 |

|

2013 |

333,049.0 |

32,067.3 |

179,160.8 |

15,303.9 |

559,581.0 |

|

2014 |

353,538.7 |

30,879.7 |

181,679.4 |

15,170.3 |

581,268.0 |

|

2015 |

331,739.7 |

30,118.8 |

195,836.9 |

18,150.4 |

575,845.8 |

|

2016 |

328.195.7 |

25,047.8 |

221,413.4 |

18,639.9 |

593,296.7 |

|

2017 |

349,101.4 |

26,944.3 |

233,038.8 |

18,603.6 |

627,688.1 |

|

2018 |

367,421.9 |

24,323.3 |

221,525.4 |

16,854.6 |

630,125.3 |

Source:

https://www.mpa.gov.sg/web/portal/home/maritime-singapore/port-statistics

Singapore

is often referred to as the leading petroleum trading hub in Asia (being the

third largest in the world, after New York and London) and one of the five

largest petroleum refining centres in the world.[18] This raw material and

its derivatives constitute the main bulk cargo handled in the port of Singapore,

subsequently processed by the highly developed petrochemical industry. The number of tanker arrivals at the port over

the years 2007–2017, as well as the volume and type of liquid bulk cargo

transported by these vessels have been collated in Table 4 (in 2018, the port

received 24,165 tankers).

Tab. 4

Tanker arrivals at the

port of Singapore over the years 2007-2017 according to the type of cargo

shipped

|

Year |

Petroleum and its

derivatives |

Chemicals |

LNG and LPG |

Total |

||||

|

number of tankers |

cargo in ‘000

tonnes |

number of tankers |

cargo in ‘000

tonnes |

number of tankers |

cargo in ‘000

tonnes |

number of tankers |

cargo in ‘000

tonnes |

|

|

2007 |

14,343 |

367,249 |

3511 |

29,635 |

1458 |

48,564 |

19,312 |

445,448 |

|

2008 |

13,756 |

378,629 |

3843 |

34,226 |

1861 |

71,561 |

19,460 |

484,415 |

|

2009 |

14,059 |

424,172 |

4337 |

43,854 |

1684 |

59,591 |

20,080 |

527,618 |

|

2010 |

15,093 |

467,715 |

4607 |

48,393 |

1655 |

53,286 |

21,355 |

569,394 |

|

2011 |

15,861 |

536,895 |

4588 |

49,011 |

1831 |

66,776 |

22,280 |

652,682 |

|

2012 |

15,702 |

561,785 |

4534 |

49,854 |

1994 |

82,200 |

22,230 |

693,839 |

|

2013 |

16,125 |

567,950 |

4493 |

49,833 |

1999 |

87,060 |

22,617 |

704,884 |

|

2014 |

15,349 |

555,127 |

4629 |

51,924 |

2240 |

100,413 |

22,218, |

707,464 |

|

2015 |

14,676 |

567,341 |

5083 |

58,032 |

2303 |

94,072 |

22,062 |

719,445 |

|

2016 |

15,805 |

620,756 |

5209 |

60,336 |

2681 |

99,757 |

23,695 |

780,849 |

|

2017 |

16,895 |

702,926 |

4763 |

56,268 |

2753 |

116,642 |

24,411 |

875,837 |

Source:

https://www.mpa.gov.sg/web/portal/home/maritime-singapore/port-statistics

The port of Singapore also

provides supplies and repair services for vessels passing through the Strait of

Malacca. In 2017, out of the total number of 216,342 port arrivals, as many as

71,682 (33%) were due to an intent to replenish fuel or food supplies or to

perform repairs.[19]

9. CONCLUSIONS

The seaport has been

performing a key role in the Singaporean economy for years. The

government’s policy of maintaining low import tariffs affects the

port’s revenues, technological progress and dynamically growing trade

with China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia,

the USA and the European Union. This small city-state has been consistently

implementing the policy of free trade, perceiving it as an opportunity for

further development and increasing competitiveness in relation to other

dynamically developing economies of Asia.

Singapore’s

particularly attractive investment climate and stable political environment

attract foreign direct investment from global investors and institutions. The business-friendly

environment is not only conducive to investment but also boosts the economy.

The service sector provides jobs for 80% of workers and creates more than 75%

of the GDP, while ca. 20% of the GDP is produced by the industry and the

secondary sector employs 15% of all the workforce. Additionally, a very

important factor in this context is the link between the businesses operating

in Singapore and state-owned enterprises. Business groups established as

holdings or trading companies create a larger outlet market and provide access

to foreign technologies or managerial methods. This is particularly important

for the development of key economic sectors such as trade, shipping and

logistics, all the more so since Singapore’s economic growth is heavily

dependent on exports, especially of electronics, petroleum products, chemicals,

medical and optical equipment, pharmaceuticals, as well as transport, business

and financial services.

Considered particularly

important in Singapore is its high-end manufacturing based on the latest

technologies, including semiconductors and consumer electronics, as well as

machinery, transport equipment and ships. Public funds are typically allocated

in sectors which may become the future of economic growth, such as aviation and

aeronautics, precision engineering and life sciences, including biotechnology,

medical equipment and pharmaceuticals. The Singaporean authorities are also

committed to investing in infrastructure projects and new industrial parks.

It should be noted that

Singapore suffered greatly from the global financial crises of 2001 and 2009,

having experienced some of the most severe recessions since it gained

independence. The collapse in prices in most of the world’s leading stock

exchanges and the abrupt drop in industrial production also exerted a negative

impact on its export-dependent economy, which declined by 1-2% at the time.

However, with time there was an observed rapid recovery and a return to dynamic

growth, both in the years 2004-2007 and in 2010, when the annual growth rate

came to 15.2%, one of the world’s highest.

Singapore is an active

member of NATO, ASEAN and other international trade organisations. The country

has entered into numerous free trade agreements, including the one signed with

the European Union in 2015 as the first ASEAN member state.

References

1.

Buková Bibiána, Eva

Brumerčíková, Pavlína Kolářová.

2015. “A study of a logistics transport chain in the transport of

selected commodity from eastern Europe to China”. Naše More 62(4): 256-263.

2.

Centre for Liveable Cities (CLC).

Available at:

http://www.clc.gov.sg/documents/books/research-workshop/2016/singapore-port-and-the-city-heart-of-innovation-presentation-paper.

3.

Civil Services

College. Available at: https://www.csc.gov.sg/articles/connecting-to-the-world-singapore-as-a-hub-port.

4.

Departament of Statistics Singapore.

Available at: https://www.singstat.gov.sg/modules/infographics/economy.

5.

Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/places/singapore/.

6.

Heng Derek. 2005.

„Continuities and Changes: Singapore as a Port-City over 700

Years”. Biblioasia. Singapore: National

Library Board (1): 12-16. ISSN 0219-8126.

7.

InterNations. Available at: https://www.internations.org/singapore-expats/guide/29457-economy-finance/the-economy-of-singapore-16045.

8.

InterNations. „The Economy of

Singapore”. Available at: http://www.internations.org/singapore-expats/guide/29457-economy-finance/the-economy-of-singapore-16045.

9.

Jurong Port. Available at: http://www.jp.com.sg/our-expertise/terminals/cement-terminal/.

10.

Jurong Port. Available at:

http://www.jp.com.sg/our-expertise/terminals/steel-terminal/.

11.

Maritime Singapore Connect. Available

at: https://www.maritimesgconnect.com/features/spotlight/5-things-you-should-know-about-new-tuas-mega-port.

12.

Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore

(MPA). Available at: http://www.mpa.gov.sg/web/portal/home/about-mpa.

13. Maritime

and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA). Available at: www.mpa.gov.sg/web/portal/home/maritime-singapore/port-statistics.

14. Ministry

of Trade and Industry, Singapur. Available

at: https://www.mti.gov.sg/.

15.

Ministry of Transport Connecting,

Singapore. Available at: https://www.mot.gov.sg/about-mot/sea-transport/advancing-the-maritime-industry.

16.

Obed Ndikom, Nwokedi Theophilus C., Sodiq

Olusegun Buhari. 2017. “An appraisal of demurrage policies and charges of

maritime operators in nigerian seaport terminals: the shipping industry and

economic implications”. Naše

More 64(3): 90-99.

17.

Ojadi Francis, Jackie Walters. 2015.

“Critical factors that impact on the efficiency of the Lagos

seaports”. Journal of Transport and

Supply Chain Management 9(a180): 1:13. ISSN: 2310-8789.

18.

Operating Revenue and

Total Expenditure as at 2017 estimate. Singapore Budget 2017. February 2017.

19.

Port of Singapore. Available

at: https://www.ship-technology.com/projects/portofsingapore/.

20.

PSA SINGAPORE. Available at: http://www.singaporepsa.com/about-us.

21.

Safety4Sea. Available at: https://safety4sea.com/shanghai-continues-as-the-worlds-busiest-container-port/.

22.

Singapore - Oil and Gas. Available at:

http://www.export.gov/article?id=Singapore-Oil-and-Gas.

23.

Sumayah Goolam Nabee, Jackie Walters.

2018. “Liner shipping cascading effect on Southern African Development

Community port strategies”. Journal

of Transport and Supply Chain Management 12(a394): 1:12. ISSN: 2310-8789.

24.

Tank news international. Available

at: https://www.tanknewsinternational.com/jurong-port-tank-terminals-officially-launched/.

25.

Temasek. Available at: http://www.temasek.com.sg/en/who-we-are/about-us.html.

26.

The Maritime Executive. Available

at: https://www.maritime-executive.com/article/two-new-berths-planned-for-cosco-psa-terminal-singapore.

27. The Straitstimes. Available at: https://www.straitstimes.com/business/an-icon-of-the-port-of-singapore.

28. The Straitstimes. Available at: https://www.straitstimes.com/business/tanjong-pagar-terminal-cleared-ahead-of-schedule.

29.

The

Straitstimes. Available at: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/full-steam-ahead-for-new-tuas-mega-port.

30. The Straitstimes. Available at: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/spore-plans-to-keep-port-attractive.

31.

The week in Asia. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/business/article/2148878/singapores-tuas-mega-port-plain-sailing-ahead.

32.

World Bank. 2017. Doing Business 2018: reforming to create

jobs – Singapore (English). Doing Business 2018. Washington, D.C.:

World Bank Group.

33.

Yap C., R. Lum. 1990. “A

port’s story, a nation’s success”. Singapore: Times Editions.

Received 01.11.2019; accepted in revised form 22.12.2019

![]()

Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License