Article

citation information:

Buczak, I., Giza, P., Janas, A.,

Kosiba, A., Sobinek, K., Rysak, M., Panicz, J., Płaneta, P., Lipień, K.,

Kogut, W., Masoumi, H.E. Socio-demographic and land use determinants of non-commute travel

generation in Cracow, Poland. Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2020, 106, 5-28. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2020.106.1.

Izabela

BUCZAK[1],

Paulina GIZA[2], Aneta

JANAS[3],

Andrzej KOSIBA[4],

Katarzyna SOBINEK[5], Monika

RYSAK[6], Justyna

PANICZ[7],

Patrycja PŁANETA[8],

Krzysztof LIPIEŃ[9], Witold KOGUT[10], Houshmand E. MASOUMI[11]

SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC

AND LAND USE DETERMINANTS OF

NON-COMMUTE TRAVEL GENERATION IN CRACOW, POLAND

Summary. The circumstances of passengers’ decisions and

behaviours concerning non-commute urban travels in Eastern Europe is not

well-studied; most of the studies on this topic was done on Western societies.

This paper presents the results of a study on Cracow, Poland. This study is

based on a survey in two neighbourhoods of different urban forms in Cracow, one

with central structure with compact land use and the other a representative of

socialist urban form with big residential blocks and no central local places.

The survey was carried out from January to February 2019 with 426 inhabitants.

The results of the Ordinary Least Square models reveal that age, daily

activity, the place of shopping, frequency of shopping in the vicinity of

homes, and frequency shopping activities outside in farther places are

significantly correlated with the frequency of non-work trips in Cracow. The

sprawled decentral district produces a high correlation between shopping trips

outside the district and the overall non-work trip frequency, referring to the

failure of the socialist urban form to keep non-work trips inside the districts

by the presence of local facilities like shops and retail. It is discussed in

this paper that such correlations may be very much context-specific, as there

are some differences between the findings of this paper and those of international

findings in high-income and developing countries.

Keywords: urban transportation

planning, travel behaviour, non-work trip generation

1. INTRODUCTION

The existing studies about Eastern European cities

provide limited understanding of the determinants of home-based non-commute

urban travels. In other words, we don’t know what exactly defines the

characteristics of these urban trips. Like several Eastern and Central European

countries, Polish cities are less studied compared to their Western counterparts.

A literature review was done in this study, the results of which are presented

below, show that there is some data about non-work urban travels in Polish

cities, but it is difficult to integrate land use and urban form in analytic

studies based on these data. Moreover, the number of studies that provide

statistical models of non-commute trips using primary disaggregate data is

limited, hence, it is difficult to draw an inclusive conclusion about the

determinants of these urban trips. To be more specific, we do not know exactly

if the socio-economic factors or other determinants such as land use traits lay

significant effects on the number of home-based non-commute trips in Poland.

The goal of this study was to assess

the socio-demographic and build environment relationships with mode choice for

individual visitors found for non-work travel and contrast these outcomes with

establishment-level analysis of mode shares in Cracow, Poland. To do this, we

utilised a customer intercept survey at very different

establishments—convenience stores, restaurants, and bars. The analysis

depends on destination-based information, unlike a majority of the travel

behaviour research, which generally depends on data gathered from home areas.

Additionally, a couple of other studies control for specific land-use types.

This manuscript is continued by a

literature review of urban travel behaviour in Poland and existing data about

non-commute travels. Then, the methods including survey, data, case-study

areas, and analysis methods of this study are introduced, and findings are

presented in the form of descriptive statistics and model fit. Finally, the

relations between the empirical findings in Cracow, Poland with the

international studies, and well as the concluding remarks about urban and

transport planning in Poland were presented.

1. TRAVEL CHARACTERISTICS AND THE NON-COMMUTE

TRIPS

Recent urban transportation planning

literature has found various associations between transportation requirement

and different elements like the accessibility of facilities, the dimension of

motorisation, city structure, the pace of financial development, neighbourhood

culture, etc. [14,18,19].

It is still desirable to

investigate the connections among these components to have the capacity to get

a handle on present and future travel request in many geographical contexts,

especially Eastern Europe.

Individual travel choices are suppose to

be impacted by the places where people live and work. Many blame

“sprawl” for congestion and overuse of automobiles, and trust that

transit access, roads, the distance to shops and services, and spatial

attributes of the manufactured environment may all impact how people travel to

shops, to activities, and to other places not related to work travel. In any case,

it is widely acknowledged that such influences are complex. Some empirical

research recommends that there is a strong connection between the built

environment and non-commute travels, while other research, often using

different model specifications, data, or measures of travel, find little or no

relationship. This difference is partially because relationships between travel

and the built environment are undertheorized. „The

conceptualisation and operationalisation of “density”

provide a primary example. Development density is a basic planning concept, however, in practice,

it is complex and difficult to implement for use in controlling trip

characteristics” [7,11,23].

In the course of the past three

decades, a very large body of research has risen on how built environments

impacts travel. Studies have

analysed travel in numerous dimensions: the amount of trips, the frequency of

trips, trip goals, and trip lengths, and travel modes. Measures of the built

environment are incorporated as continuous objective measures, subjective

measures got from survey participants, or categorical measures derived by

specialists. Travel is normally analysed at either an aggregate level or a

disaggregate level. Aggregate analyses are typically performed to estimate mode

splits or vehicle miles travelled (VMT) at the level of TAZs, census tracts, or

metropolitan areas. Disaggregate analyses are typically actualising at the

level of the individual or household, and outcomes are often individual travel

mode choices or number of trips made by mode. Disaggregate analysis let for more complete

models, as there is finer detail in spatial, temporal, and personal information

[12]. Fig. 1 illustrates

the percentages of travels based on travel purposes in six international cities

with different cultures. As

seen, the share of non-work travels may differ dramatically in accordance with

the culture and geographies of the cities.

The share of such studies in

different regions and countries of the world is different. A large part of the studies done on urban

travel behaviour and especially the characteristics of the non-commute travels

are related to the USA. Although the territory of the USA is huge and diverse,

some similarities can be noticed in the communication behaviour of the population.

A lot of research has been done on this topic with most of them focused on

large and medium-sized cities and commute travels. All studies regarding

commute and not commute exchange such factors as age, sex, income, car

ownership, land use mix, street networks employment and emphasise the

importance of their role in shaping travel. Studies about preferences and dependencies on

non-work travel among Americans were carried out, inter alia, in California

(San Francisco Bay Area) and in Boston

[6].

Generalising research that has been

improved over the recent years; conclusions can be drawn about residential

travel behaviour: people with high income prefer to travel alone rather than

with someone else, prefering also the shared-ride mode than the transit mode. The more cars in the household, the less

likelihood of using one vehicle by several people. If someone lives on the

outskirts of the city, he uses more car to travel. Additionally, that person travels less on

non-work trips than a resident who lives in the centre [2].

Fig. 1. Share of the trip purposes based on time of the

day in six international cities

[22]

High

mobility of people contributes to the reduction of social and economic

differences between regions. It is also very beneficial from an economic point

of view. Several recent empirical studies

have shed light on the causal relationships that underlie the correlations

between a built environment and travel behaviour [13]. In

Europe, as in the United States, people do not change their place of residence

because of entertainment and other motivations like shopping and entertainment

but their main motive is usually proximity to workplace. This is something

common in parallel with Poland, where like several other European countries,

people would travel on a small distance rather than long trips. It is a

convenience to change the residence place when someone starts a new job. If one

gets employment in another city, he rents a flat there and moves permanently.

As it appears from the PageGroup survey in Europe, private car access to for example shopping has the most proponents. 66% of all respondents admitted that they usually choose a private means of transport. Over two fifths are in a way forced into the car - because they have limited possibilities of using public transport. In all of Europe, 34% of people use public transit, with most of them (75%) appreciating its effectiveness. An additional advantage of public transport means is their relatively low costs (60%) and speed of getting to different motivations (44%) – especially when you can commute by metro or high-speed train. For 40% of respondents, a significant advantage of public transport is to avoid parking problems. Among the surveyed countries: Austria and Switzerland exceed 90% satisfaction with public communication. The European average is lowered by Italians; only 54 per cent. People using public communication acknowledge its effectiveness.

In Poland, a series of deliberations

titled Comprehensive Travel Study (KBR) have been carried out mostly in large

cities. They concern surveys

in household and measurements of vehicles and travellers in private and public

transport. The intention is to learn about the daily transport user’s

behaviour of the inhabitants that pursue rational transport policy. On their basis is developing

transport model, which analyses the volume and conditions of traffic in the

road network and public transport depending on the changes in spatial

development (construction of a housing estate, shopping centre) and changes in

road infrastructure (construction of a road or tramway line) [22].

In Warsaw, six of such

surveys was carried out, the last of which was in 2015. The mobility rate of

Warsaw residential amounts to 1,99 trips. On a working day, almost 82 % of

residents make at least one trip per day. Residentials who do not travel so

much are elderly people (pensioners) and non- working and unemployed people.

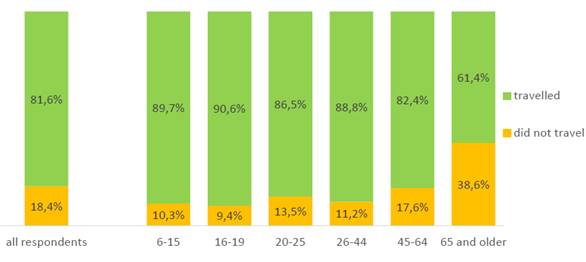

Fig. 2 shows a chart of travellers and non- travellers by age.

Fig. 2.

Travels performed by residents of Warsaw on a typical working day [22]

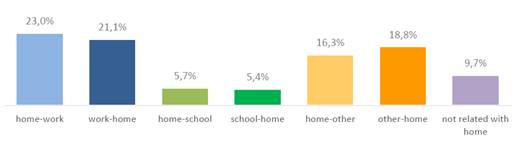

Based

on the chart (Fig. 3), the most frequent destination accounts for 44,1% trips

about motivation home – work and work – home. Next, the travel between

home and other destination 35,1% and 11,1% trips between home and place of

study. The remaining 9,7% are trips not

relevant to the home. Modal split shows (Fig. 4) that Warsaw residents

primarily travel by public transport (46,8%) or as a passenger car (31,7%).

Nearly, one in five (17,9%) trips are on foot and the rarest choice of

transport is a bike (3,1%). In all the destinations (also trips between home

and work), the choice of car in trips was purposeful by its ownership.

Three out of four

non-pedestrian travels are executed without having to change vehicles. Trips by mass transit

take place without transfers of 57,2%. The majority of trips of inhabitants of

Warsaw begin and end in Warsaw (95,5%). Only 4,5% of all trips have their

inception or destination outside Warsaw [21].

Fig. 3. Travel purposes

of Warsaw residents [22]

Fig. 4. Modal split

of the respondents [22]

In 2009, mobility

estimate of Wroclaw residents amounted to 1,87 trips (1,87 daily trips for

Wrocław inhabitants). The most trips by all day, on average 2,05 are

complied by people who have got more than two cars and residents who are 26-39

years of age. The busiest occupational group are persons working on their own

(enterprisers); they make an average of 2,59 trips daily. The house is the

basic travel destination of the inhabitants of Wroclaw and constitutes 45% of

all travels. Following destination is work, which accounts for 21% of trips [24].

Execution of the

2018 Comprehensive Travel Study shows that the mobility of inhabitants of

Wroclaw is as follows 1,7 trip/ day. The average number of cars in the

household in Wroclaw equal 0,5 (265 cars/ 1000 residents). The residents travel

by car most often (41%). While the second most frequently chosen mode of

transport is public transport (28%), then are trips on foot (24%) and travel by

bike (6%). 38% of all trips have a motivation home - work (20%) and work - home

(18%). The men often performed work and study trips. The reason for choosing

car transport in commuting is the convenience of use and short commuting time.

Whereas the reason for choosing public transport is more varied. Firstly, the

convenience of use, and secondly, the close location of stops, and third short

commuting time [8].

The fifth Comprehensive

Travel Study in Cracow was held in 2013. Based

on it, the most important indicators characterising Cracow’s transport

system were determined. 97.5% of the travels were

internal (takes place in the city of Cracow), while 2.5% was outside of the

city [3].

The survey shows that 57%

of households have access to at least one passenger car and 45% do not have a

car. The average number of home-based travels Is 2.02 trips per day. The

largest number of trips is made by people aged 30-39 (mobility rate 2.13). The

least number of trips is made by people after 60 years of age (mobility rate

1,42).

Travels about motivation

home-work (18,1%), work-home (15,8%) and other-home (19,8%), home-other (17,2%)

was the main destination of Cracow inhabitants. Public transport (36,3%) and

car (33,7%) was the dominant means of transport in the travels residents. The

share of pedestrian travel was 24, 8%. Moreover, the research indicated that

20% of residents reach Midtown by car. The reason for choosing a car is the

accessibility of travelling and the inappropriate offer of public transport and

“the nature of the work requiring the use of a car”. An incentive to opt

out of commuting to Midtown by car is the ability to reach public transport

quickly (37,1%), free parking near the city centre (36,7%) and increase of the

public transport frequency (28,3%) [20].

Primarily, the previous enactments about

Warsaw, Wroclaw, and Cracow shows that the non-commute travels in these cities

especially the home-based ones make a large percentage of the whole urban

travels. In spite of the fact that we possess these data, statistical analysis

is still needed to interpret the associations between different determinants of

trip behaviours, as well as the provenance of the mobility decisions. The

current data about Polish cities as such cannot be accurate about these

circumstances. Thus, the present study about Cracow as a typical large Polish

city was initiated.

1.1.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The research questions

answered in this study are (1) what are the determinants of non-commute travel

generation (shopping and entertainment) in Cracow, Poland?, (2) What are the

differences in terms of travel generation in compact, central districts with

those of the sprawled, decentral districts?

The general hypothesis of

this study concerns the impact of various factors on the commute and

non-commute travel generation. Traffic generating factors is location;

individual factors and socio-economic considerations; transport aspects (modal

split, availability of alternative means of transport in relation to the car,

advantages and disadvantages of different modes of transport) or land use and

urban form (number of public and commercial services, amount of greenery,

distance from the destination).

1.2.

Case study areas

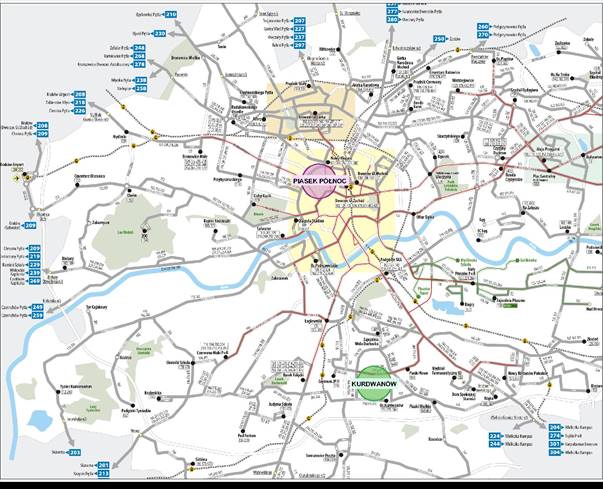

For the analysis of non-commute

travels in Cracow, two districts of the city were selected based on their

characteristics: Piasek Północ and Kurdwanów. Residential

area Piasek Północ is located in Stare Miasto district in the

central part of the historical part of Cracow, while the residential area

Kurdwanów is located on the edge of the city (south of the centre) in

Podgórze Duchackie district. In Stare Miasto district (including Piasek

Północ), 37 528 people live in a 5,59 km² area, so the

population density of the whole district is 6 710 inhab./km², while in

Podgórze Duchackie district (including Kurdwanów) 54 637

inhabitants live in 9,54 km², resulting in a population density of 5

435 inhab./km² [4].

Over the centuries, the districts of

Cracow have been influenced by historical events, including the Austrian

partitions or the German occupation. In 1991, 18 districts were established,

the territorial division of which is still valid today. The locations of the

analysed districts are presented against the background of the city of Cracow

in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. The location of the two case-study areas: Kurdwanów and

Piasek Północ

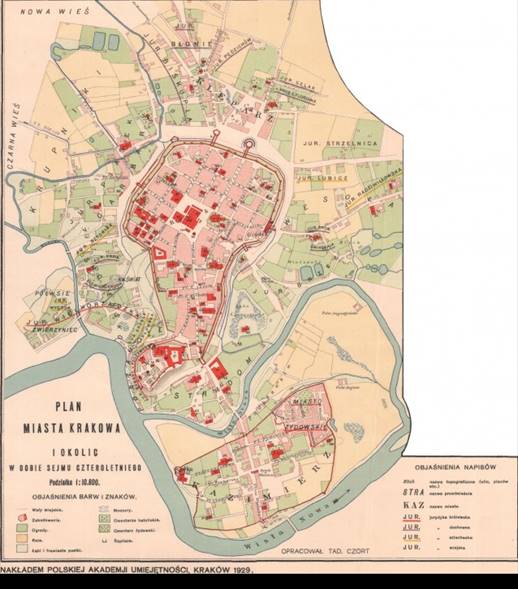

The territorial development of

Cracow over the years is presented below. The map [15] from 1788 shows the location of the housing

estate in relation to the old town. Then, Piasek Północ was not

part of Cracow, however, it was annexed to the city in later eras. Due to its

history, the area accommodates many historical and cultural values for

centuries, the layout of the streets has remained unchanged. One can also

notice the effect of urban sprawl by connecting nearby villages to Cracow.

During the Four-Year Sejm (1788-1792), it was established that suburban areas

(including Jura Piasek) joined the city. Then the city was divided into four

circuits (the equivalent of districts), the second circulation included the

analysed area.

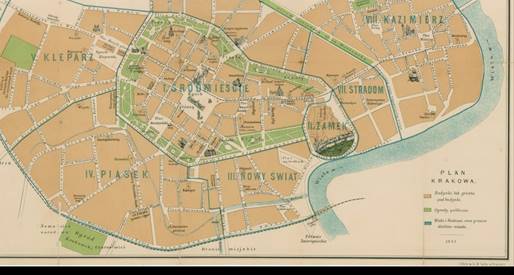

In the map from the 19th century

guide “Cracow and its surroundings” [16]. It can be noticed that the analysed Piasek

Północ estate was then defined as Przedmieście Piasek, which

was already entering the city limits. Piasek was the fourth district of Cracow

in 1891 as indicated in the book titled “Guide to Cracow and

surroundings” [17].

It is also interesting to present a public transportation network that depicts

the tramline run by the two bypasses of Cracow – Adam Mickiewicz Avenue

and Juliusz Słowacki Avenue.

The latest plan of

Cracow published in 1935 by the Polonia publishing house is the second edition

of the plan by Stanisław Wyrobek [1]. It can be noticed that Piasek Północ has slightly

changed since then, the street layout and building quarters are very similar to

the current state. Contributing to this may be the fact that during

the Second World War and the occupation, Polish Cracow was not destroyed and

devastated. One can also observe the differences in the aforementioned

tramlines. In this edition, it was not planned to be built along the alley, its

place was taken by a green belt in the middle of the street. A side map was

also inserted showing the surroundings of Cracow, where it is shown that

Kurdwanów does not belong to the city yet. In 1941, the German

occupation authorities extended the administrative boundaries of the city by

joining the surrounding municipalities and towns, creating districts of Cracow

from them, among others X – Borek Fałęcki in which

Kurdwanów is located [9].

In

1948, this extension was confirmed by Polish authorities. In the 1980s, on the

border of Wola Duchacka and Kurdwanów, a large housing estate began,

which adopted the name Kurdwanów Nowy (a central part of the estate was

created). Actual construction of the estate began in 1980. At that time, tens

of 5 and 11-storey blocks were built. Until the early nineties, the urban

structure of the housing estate was formed. Buildings were built after the era

of socialist urban planning, where they were popular affordable housing encouraged

by socialist approaches. Many new multi-family blocks erected in various

technologies and styles have been created and are still being built.

Fig. 6. Plan of the city of Cracow and the

surrounding area in the year 1788

Fig. 7. Location of Piasek

Północ Cracow in the year 1891 [10]

Piasek Północ

is mainly characterised by multi-family housing in the form of urban block and

frontage along the street. All these create a dense downtown development, in

addition, are services on the ground floor of tenements. There is a negligible

amount of greenery there. The opposite can be seen in Kurdwanów, where

there are multi-family buildings, but in the form of modernist blocks or

detached houses. The service buildings are mainly free-standing buildings or

services on the ground floor. Green areas are green companion plants or small

parks and green squares.

In terms of public

transport service, both analysed areas are good. In the case of Piasek

Północ, there are five public transport stations (all serviced by

bus, including three serviced by tram). The arrival times and distance are

convenient for transport users. While in Kurdwanów, there are seven

stations (four serviced by bus and three serviced by tram). A huge

difference is in the case of the parking situation in the two areas. Piasek

Północ does not have enough space, so the number of parking spaces

is limited, whereas Kurdwanów does not suffer from this issue so much.

In the north-western part of the estate, there is a park and ride car park

integrated with trams.

Worthy of note is the

bicycle infrastructure. In Cracow, there is a city bike system named Wavelo. It

can be noted that there are four city bike stations in Piaski

Północ and three stations in Kurdwanów. In Kurdwanów, there are no

bicycle routes, only suggested roads are indicated, while in Piasek

Północ, there is a cycling route network.

The two areas were

selected for analysis due to the diversity in terms of land development, the

number of services, and the accessibility to public transport. An important

factor was also the proximity to the centre, which generates a large number of

tourists in Piasek Północ and the fact that there are many more

commercial and public services within walking access. These above

characteristics motivated selection of the two areas, aiming at having two

different case-study areas in terms of land use.

|

|

|

Fig. 8. The urban form and layout of

the two selected areas: up: Piasek Północ; bottom: Kurdwanów

|

|

|

Fig. 9. Accessibility to bus stations (A) and

tram (T) in Piasek Północ (left) and Kurdwanów (right)

1.3.

Data and survey

The data used for this

study come from responses to questionnaires with 42 questions that included

information on urban travel behaviour of Cracow’s adults. The survey was

carried out from January to February 2019 on 426 inhabitants of the two neighbourhoods

in Cracow. Randomly selected persons on the streets of these neighbourhoods

were asked to participate in the interview. The two areas selected for the

survey differ in terms of spatial layout and structure as mentioned in the

previous section.

Piasek Północ

is a neighbourhood in a high-density area. It has a mix of residential,

business and commercial functions. There is also access to the public transport

system and good conditions for pedestrians. A little bit different is Kurdwanów.

It is a neighbourhood where building densities and the land use mixing are

lower. There residential locations dominate due to lack of retail facilities,

distance to the nearest shop is longer. However, there is access to public

transport system.

The questionnaire consisted

of four parts. The first one was related to socioeconomics. The survey asked

respondents among others about gender, age, and gross income. The second part

was focused on activities and special issues of inhabitants. The questions

referred to the frequency of travel and trip purpose. The mobility patterns

were the subject of the other part of the survey. Respondents were asked about transport

mode choice for commute and non- commute travel. The last part was focused on

perceptions, attitudes, and self-selections. The questions referred to

inhabitants’ feelings about their neighbourhood. Table 1 summarises the

variables developed based on the questions asked in the interviews.

Tab. 1

Summary of

variables

|

Section |

Variable number |

Variable |

Data Type |

Description |

|

Socioeconomic |

1 |

Gender |

Binary |

Male

or female. |

|

2 |

Age |

Continuous |

Reported

age of the respondent. |

|

|

3 |

Daily Activities |

Binary |

Work/study or none. |

|

|

4 |

Driving License Ownership |

Binary |

Possession

of a driving license by the respondent: yes or no. |

|

|

5 |

Car Ownership |

Categorical |

The

number of personal cars possessed by the respondent. |

|

|

6 |

Monthly Living Cost |

Continuous |

Reported

gross household monthly income. |

|

|

7 |

Daily Travel Cost |

Continuous |

Reported daily travel cost |

|

|

Activities and special issues |

8 |

Frequency

of Non- Commute Trips |

Continuous |

The

number of non-commute trips of the respondent during the past seven days. |

|

9 |

Shopping Place |

Binary |

The

place the respondent usually shops daily living stuff: inside the

neighbourhood or farther. |

|

|

10 |

Frequency

of Shopping Inside the Neighbourhood |

Continuous |

The

number of shopping inside the neighbourhood during the past seven days. |

|

|

11 |

Attractive

Shops in the Neighbourhood |

Binary |

Presence

of attractive shops in the neighbourhood of the respondent according to him/her:

yes or no. |

|

|

12 |

Frequency

of Shopping Outside the Neighbourhood |

Continuous |

The

number of shopping outside the neighbourhood during the past seven days. |

|

|

Mobility patterns |

13 |

Shopping/Entertainment

Mode Choice Inside the Neighbourhood |

Categorical |

Mode

choice for respondent’s shopping or recreational activities inside the

neighbourhood: car, on foot, bicycle, taxi, taxi apps, bus, train, tram. |

|

14 |

Shopping/Entertainment

Mode Choice Outside the Neighbourhood |

Categorical |

Mode

choice for respondent’s shopping or recreational activities outside the

neighbourhood: car, on foot, bicycle, taxi, taxi apps, bus, train, tram. |

|

|

15 |

Frequency of Commute Trips |

Continuous |

The

number of commute trips of the respondent during the past seven days. |

|

|

16 |

Commute Mode Choice |

Categorical |

Mode

choice for respondent’s commute trips: car, on foot, bicycle, taxi,

taxi apps, bus, train, tram. |

|

|

17 |

Reason for Mode Choice |

Categorical |

|

|

|

18 |

Frequency

of Public Transport Travels |

Categorical |

The

usual frequency of the respondent’s public transportation ridership

according to him/her: every day, a few times per week, a few times per month,

rarely, almost never. |

|

|

19 |

Reason for

Non-Public Transport Use |

Categorical |

The

respondents were asked “If you do not use public transit, what is the

reason?” Options: It is not comfortable, It is expensive, Station/bus

stop is far away, There is no public transport, It is slow Social problems, I

prefer my own car. |

|

|

20 |

Subjective

Security of Public Transport |

Categorical |

The

level of the securing of public transportation according to the

respondent’s perception: very secure, secure, medium, insecure, and

very insecure. |

|

|

21 |

Reason for

Public Transport Use |

Categorical |

The

respondents were asked “If you do use public transit, what is the

reason?” Options: It is not comfortable, It is cheap, Station/bus stop

is near, It is fast, I do not have a car. |

|

|

Perceptions, Attitudes & Self Selections |

22 |

Sense of

Belonging to the Neighbourhood |

Binary |

Respondent’s

perception about his/her sense of belonging to the neighbourhood: yes or no. |

|

23 |

Entertainment Place |

Binary |

The

place the respondent usually goes to entertainment activities: inside the

neighbourhood or farther. |

|

|

24 |

Residential Location Choice |

Categorical |

The

main reason of choosing the living place and the neighbourhood from the

following options: affordability, proximity to working place/school,

attractive surrounding environment, live here since I was born/my childhood, good public transport. |

|

|

25 |

Advantages of the Neighbourhood |

Categorical |

The

respondents were asked: “What kind of advantages does your

neighbourhood have?“ Options: Lots of public space, There is good

public transportation, Well connected to the centre. |

|

|

26 |

Disadvantages of the Neighbourhood |

Categorical |

The

respondents were asked: “What disadvantages does your neighbourhood

have?” Options: Lots of traffic jams, Polluted area, Lack of safety,

Loud at night, High costs of living. |

|

|

27 |

Last Relocation Time |

Continuous |

The

number of years passed from the last residential relocation of the

respondent. |

|

|

28 |

Personal Character |

Binary |

The

respondents were asked: “Which personal character is true about

you?” Options: I enjoy driving a car very much, I am pro-environment, I

work all the time, I strictly follow my hobbies, I am a social person: yes or

no |

1.4.

Analysis method

Based on the data

obtained as a result of the surveys, linear regression models were generated,

with the aim of finding the correlation between the frequency of home-based

non-work travels as an independent variable and the dependent variables that

were considered to be important according to the existing literature. The

modelling was continued by eliminating insignificant variables until a

satisfactory R² resulted. Three models associated with non-work travel

frequency was developed for individual areas. Each model was developed assuming

a confidence level equal to 95%.

2.1.

Descriptive statistics

In the linear regression model for non-commute travel generation model,

8 variables were used: 4 discrete and 4 continuous. These variables are

presented in Table 2.

Tab. 2

Description of variables

|

Variable |

Type |

Description |

|

Age |

continuous |

Person’s age |

|

FreqNonCommuteInDistrict |

continuous |

Frequency of non-commute travels

in district |

|

FreqNonCommuteOutside |

continuous |

Frequency of non-commute travels

in district |

|

NonCommuteTotal |

continuous |

Total number of non-commute trips |

|

DailyActivity |

dummy |

Daily activity: work or study (1),

no work or study (0) |

|

DistrictShoppingPlace |

dummy |

The most frequent place of

shopping: district (1), farther (0) |

|

AttractiveShops |

dummy |

Attractive shops In the

neighbourhood: present (1), not present (0) |

|

DomModeOutside |

dummy |

Dominant mode outside district:

car (1), non-car (0) |

Descriptive statistics for discrete variables used in the model is shown

in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. Other variables were not significant enough

for use in the model.

Tab. 3

Discrete variables used in the model

|

Variable |

n |

Range |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean |

Std. dev. |

Variance |

|

Age |

426 |

68 |

10 |

78 |

34.51 |

14.71 |

216.33 |

|

FreqNonCommuteInDistrict |

426 |

15 |

0 |

15 |

3.02 |

1.88 |

3.52 |

|

FreqNonCommuteOutside |

426 |

18 |

0 |

18 |

1.75 |

2.10 |

4.41 |

|

NonCommuteTotal |

426 |

26 |

0 |

26 |

3.41 |

3.37 |

11.36 |

Tab. 4

Continuous variables used in the model

|

Variable |

Option |

Overall Sample |

Kurdwanów |

Piasek Północ |

|||

|

Count |

Column N % |

Count |

Column N % |

Count |

Column N % |

||

|

DailyActivity |

work/study |

386 |

90.6% |

196 |

90.3% |

190 |

90.9% |

|

no work/study |

40 |

9.4% |

21 |

9.7% |

19 |

9.1% |

|

|

DistrictShoppingPlace |

district |

281 |

66.0% |

138 |

63.6% |

143 |

68.4% |

|

farther |

145 |

34.0% |

79 |

36.4% |

66 |

31.6% |

|

|

AttractiveShops |

yes |

293 |

68.8% |

149 |

68.7% |

144 |

68.9% |

|

no |

133 |

31.2% |

68 |

31.3% |

65 |

31.1% |

|

|

DomModeOutside |

car |

148 |

34.7% |

92 |

42.4% |

56 |

26.8% |

|

non-car |

278 |

65.3% |

125 |

57.6% |

153 |

73.2% |

|

2.2. Model fit

As shown in Table 5, for the overall sample, the strongest impact over

number of the non-commute travels has the number of non-commute travels outside

the district (FreqNonCommuteOutside), which is 0.650. It means that for

a one-point increase of non-commute travels outside the district is an increase

of 0.650 non-commute travels overall. Less significant variables are the

frequency of shopping in the district (FreqNonCommuteInDistrict), which

is 0.247, and Age, which is -0.200. For frequency of shopping in the district,

it is 0.247 change of dependent variable per one travel increase, and for Age,

it is -0.200 change of non-commute travels per one-year increase of age. The

rest of the independent variables are the least significant. These are daily activity

(DailyActivity), main district of shopping (DistrictShoppingPlace),

presence of attractive shops in the district (AttractiveShops) and dominant

mode outside the district (DomModeOutside).

Fig. 10. Continuous variables in relation to frequency of non-commute

travels and curves with the best R2

Fig. 11. Dummy variables in relation to frequency of non-commute travels

Tab. 5

Model parameters for the frequency of

non-commute travels in the overall sample

|

Variable |

Unstandardised

Coefficients |

Standardised Coefficients |

t |

P |

|

|

B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

|||

|

Intercept |

2.854 |

0.721 |

0.000 |

3.956 |

<0.001 |

|

Age |

-0.046 |

0.009 |

-0.200 |

-4.883 |

<0.001 |

|

DailyActivity |

-0.915 |

0.464 |

-0.079 |

-1.971 |

0.049 |

|

DistrictShoppingPlace |

-0.576 |

0.281 |

-0.081 |

-2.049 |

0.041 |

|

FreqNonCommuteInDistrict |

0.445 |

0.067 |

0.247 |

6.657 |

<0.001 |

|

AttractiveShops |

0.463 |

0.261 |

0.064 |

1.777 |

0.076 |

|

FreqNonCommuteOutside |

1.043 |

0.061 |

0.650 |

17.117 |

<0.001 |

|

DomModeOutside |

-0.390 |

0.255 |

-0.055 |

-1.528 |

0.127 |

Achieved model fit is shown in Table 6 - R2 is equal 0.496,

being decent according to linear regression analysis method, explaining 50% of

the variability of the response data around its mean.

Tab. 6

Model validation for overall sample

|

Measure |

Sum of Squares |

df |

F |

P |

|

Regression |

2395.6 |

7 |

58.78572968 |

<0.001 |

|

Residual |

2433.5 |

418 |

||

|

Total |

4829.1 |

425 |

||

|

Multiple R |

0.704 |

|||

|

R Square |

0.496 |

|||

|

Adjusted R Square |

0.488 |

|||

It is notable that the impact of independent variables in both districts

is different, as shown in Tables 7 and 8 for Kurdwanów and Piasek

Północ, respectively. While the frequency of non-commute travels

outside the district (FreqNonCommuteOutside) has a very strong impact in

the Kurdwanów sample (0.877), in the Piasek Północ sample,

it is less than a half of that (0.418). The other significant difference

between the two samples is for the frequency of non-commute travels in the

district (FreqNonCommuteInDistrict) – 0.094 for Kurdwanów

and 0.357 for Piasek Północ. In the case of dependent variable Age, there is compliance between two

districts, however, they differ in numbers – in Kurdwanów, the

impact of variable Age is higher than in Piasek Północ

(-0.213 and -0.140). Other

standardised coefficients of independent variables of both districts also

comply in sign but in some cases, the numbers are different. Independent

variable AttractiveShops does not have considerable impact in

Kurdwanów as it has in Piasek Północ (0.017 and 0.101) and

similarly for other independent variables. Results show how big the differences

are between the two districts. For Kurdwanów, there are different

variables affecting the dependent variable than in Piasek Północ.

Tab. 7

Model parameters for frequency of

non-commute travels in Kurdwanów sample

|

Value |

Kurdwanów |

||||

|

Unstandardised

Coefficients |

Standardised

Coefficients |

t |

P |

||

|

B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

|||

|

Intercept |

3.030 |

0.576 |

0.000 |

5.259 |

<0.001 |

|

Age |

-0.043 |

0.007 |

-0.213 |

-5.711 |

<0.001 |

|

DailyActivity |

-0.792 |

0.382 |

-0.077 |

-2.070 |

0.040 |

|

DistrictShoppingPlace |

-0.292 |

0.241 |

-0.046 |

-1.211 |

0.227 |

|

FreqNonCommuteInDistrict |

0.163 |

0.063 |

0.094 |

2.600 |

0.010 |

|

AttractiveShops |

0.109 |

0.226 |

0.017 |

0.482 |

0.630 |

|

FreqNonCommuteOutside |

1.051 |

0.045 |

0.877 |

23.390 |

<0.001 |

|

DomModeOutside |

-0.275 |

0.209 |

-0.045 |

-1.314 |

0.190 |

Tab. 8

Model parameters for frequency of

non-commute travels in Piasek Północ sample

|

Value |

Piasek

Północ |

||||

|

UnstandardisedCoefficients |

Standardised

Coefficients |

t |

P |

||

|

B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

|||

|

Intercept |

1.602 |

1.482 |

0.000 |

1.081 |

0.281 |

|

Age |

-0.036 |

0.020 |

-0.140 |

-1.818 |

0.070 |

|

DailyActivity |

-0.149 |

0.952 |

-0.012 |

-0.157 |

0.876 |

|

DistrictShoppingPlace |

-0.848 |

0.516 |

-0.107 |

-1.644 |

0.102 |

|

FreqNonCommuteInDistrict |

0.655 |

0.114 |

0.357 |

5.752 |

<0.001 |

|

AttractiveShops |

0.779 |

0.473 |

0.101 |

1.647 |

0.101 |

|

FreqNonCommuteOutside |

1.013 |

0.155 |

0.418 |

6.553 |

<0.001 |

|

DomModeOutside |

-0.253 |

0.502 |

-0.032 |

-0.504 |

0.615 |

For Kurdwanów sample, model fit is significantly better than for

Piasek Północ Sample, as shown in Tables 9 and 10. While 77% of

cases can be explained for Kurdwanów Sample, only 35% can be explained

for Piasek Północ Sample.

Tab. 9

Model fit for Kurdwanów sample

|

Measure |

Sum of Squares |

df |

F |

P |

|

Regression |

1533.5 |

7 |

97.964 |

<0.001 |

|

Residual |

467.4 |

209 |

||

|

Total |

2000.9 |

216 |

||

|

Multiple R |

0.875 |

|||

|

R Square |

0.766 |

|||

|

Adjusted R Square |

0.759 |

|||

Tab. 10

Model fit for Piasek Północ

sample

|

Measure |

Sum of Squares |

df |

F |

P |

|

Regression |

980.4 |

7 |

15.812 |

<0.001 |

|

Residual |

1789.2 |

202 |

||

|

Total |

2769.6 |

209 |

||

|

Multiple R |

0.595 |

|||

|

R Square |

0.354 |

|||

|

Adjusted R Square |

0.332 |

|||

3. DISCUSSION

The findings of this study provide some

basic ideas on how to manage non-commute travels within the Polish or

Central/Eastern European large cities. It is often intended to decrease the number of

commute trips, however, due to the psychological needs for mobility, this is

not the aim for non-commute trips. However, it is meant to decrease the levels of car dependency on these

trips. For that, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of the relations

between the frequency of non-commute travels with several perceived,

socio-demographic and built environment factors. These interrelations and

associations are hypothesised to be under the influence of the geographic and

cultural context. The context can have influences on mobility behaviours such

as the decision to go for shopping or entertainment in case there are limited

facilities for doing these activities in the vicinity of the living place. Such

a decision may or may not be a context-sensitive one. Nevertheless, very

limited studies have tested this hypothesis in the case of travel generation,

particularly non-commute trips.

There are examples that show the presence

of such cultural differences. For instance, age is not a significant descriptor of non-work trip

generation in Southern California [5] but it is in Cracow according to the findings of this study. In contrast, gender is a significant

descriptor in California but it is not in Cracow (it was eliminated from the

model because of its insignificance). Moreover, the presence of more retail in

the living area is marginally associated (in 10 per cent level) with less

non-commute trips in Southern California, while in Cracow, it is marginally

significant but the direction is opposite, in other words, more retail is

correlated with more non-commute trips. Such contextual differences in travel

behaviour are also observable between Cracow and Nigeria as a representative of

developing countries. In

a semi-urban industrial cluster of southwest Nigeria, a significant positive

correlation was found between monthly income and car ownership with a non-work

trip, while in Cracow, these variables were eliminated from the models because

of their insignificance.

These examples show how non-commute travel

behaviours are context-specific, but such comparisons are usually difficult to

conduct, because of the methodological inconsistency of non-work travel

investigations. However, the above two comparisons can slightly prove the

hypothesis of the existence of such cultural differences. However, more similar

studies are needed in order for it to be accepted or rejected.

The most influencing factor

determining the generation of non-commute travel in the two studied areas

(Piaski Północ and Kurdwanów) is the frequency of non-work

related activities (entertainment, shopping) within the analysed urban unit.

Social and cultural issues also affect the analysed model, however, to a lesser

extent. First of all, it concerns age; the older the respondents were, the less

non-commute travels they did. In the case of the Kurdwanów, the daily

activity of the respondents and the choice of the dominant mode of transport,

which they use to make purchases outside the area of residence, have a major

impact on the generation of non-work-related journeys. However, in the case of

the Piaski Północ estate, the frequency of shopping in the vicinity

of the place of residence and the availability. Attractive stores in the area

also played a large role. The presence of attractive service premises near the

place of residence for both analysed areas does not affect non-commute travel

significantly. However, from the point of view of spatial planning, this is one

of the most important determinants. This emphasises the role of urban and

spatial planning in providing attractiveness in urban form and local

facilities. This confirms the hypothesis that the attractiveness of spaces and

destinations can encourage people to change their mobility patterns and

behaviours.

Piaski Północ, due to its historical compact

urban layout, is difficult to modernise. However, some small free spaces can be

found in it to improve the attractiveness, especially combined with active

transportation routes and tracks. Quarters in the form of a frontage are a

spatial barrier that is difficult to circumvent. To respect its history and

character, it is worth using in this area instead of hard infrastructural

instruments – “soft” measures instruments. Above all, it is

worth focusing on better mobility management in this area, by creating good

conditions for travelling with pedestrian trips, public transport, bicycles, it

is also worth focusing on the promotion of sustainable transport. In the case

of bus transport, Piaski Północ has good access to public

transport, so improving the public transport service in the form of the launch

of a new bus or tram is unnecessary. It is worth focusing on cycling, which is

in poor condition in the estate. It may be valuable creating a one-way street

or removing parking spaces for a designated cycle route. Moreover, in the place

of the gaps between the side buildings, create a multi-storey car park, whose

façade will harmonise with the character of the area. As a result, there

will be more space for cyclists and pedestrians on the street, and the space

will be less chaotic. It is worth entering a cycling route between city bike

stations and Łobzowska Street. The introduction of attractive pedestrian

routes between public transport stops and large traffic generators is also

worthy of notice. Pedestrian access, varied with small architecture and

greenery in the form of rows of trees, shrubs and low noise level, increases

non-motorised trips. It is also advisable to pay attention to people with

reduced mobility - mothers with prams, people with disabilities, elderly people

or tourists with suitcases. The topography of the estate indicates that the

area is flat, so there is no need for any additional ramps, but it is necessary

to lower the sidewalks and ensure that the pavement surface is as good as

possible – without any curves or convexities.

The situation is different in the

second analysed area (Kurdwanów), where there are large differences in

altitude in the southern part. There are stairs, which are not enough that in

many cases are not adapted for people with limited mobility. In the older,

southern part, there is a lack of access for disabled people, and the sidewalks

are in a poor technical condition - with visible losses, bumps and

irregularities. The entire estate should be adapted to this group of people,

because many older people, families with children and prams or shoppers move

around the place. The space itself is well-designed, there is a park, alleys

designed only for walking and cycling, hiking trips take place among greenery

and the noise is low. Due to the occurrence of many crimes against the

pseudo-football background, the entire facility should be better lit, and

additional city monitoring system should be introduced at stops and access

points. In the case of bicycle traffic in the analysed area, there are no

higher-order roads than local and collective roads (except for roads that are

the boundaries of the housing estate), which is the reasoning cycling is

carried out on streets without designating additional bicycle lane. It would be

better to separate bike traffic from pedestrians and cars on the busiest

streets - such as Herberta, Stojałowskiego, Halszki or Witosa Street.

Public transport in the form of bus and tram transport is also in good

condition. It would be a good idea to introduce an accelerated route to the city

centre. Presently, from the “Os. Kurdwanów” stop (the

southern boundary of the estate) to the city centre is about 45 minutes, which

is twice as long as in the case of the tram suburb located in the north. It is

also worth introducing an accelerated bus line that would lead through the

interior of the estate. The road should have a meander-like character, that is,

it should take as many people as possible, it could be led through Bojki and

Wysłołuchów streets, which would make the middle of the estate

better communicated. In the case of spatial planning, there should be at the

bus stops, buildings with the greatest building intensity, so that the stops

will be able to handle the appropriate number of passengers. However, it should

be remembered that too high building intensity and too high building density

can reduce the quality of life of residents. It is also worth introducing a

greater functional diversity, which will increase the amount of pedestrian

travel over car journeys because the distance between the source and the

destination will be reduced.

In general, the feedback of this

study to spatial planning for the purpose of affecting non-work travels is to

provide more attractive local facilities such as shops and retail. According to

the findings of this paper, this will lay influence on the number of

non-commute trips of older people in the vicinity of their houses. Since these

travels are done in short distances, it is probable that they are

non-motorised. If so, spatial planning can have causal impacts on the sustainability

of urban mobility.

When considering the contribution to

knowledge, this study has identified the impact of various factors on the

commute and non-commute travel generation. A major limitation of this study is

the inability of the available data to capture dynamic changes. The

investigation is limited by self-reported travel behaviours. Furthermore,

employment status and job type are important contributors in determining

residential location, neighbourhood preference, and mode of travel to work, and

these were not examined in any detail in this study. Neighbourhoods were

defined based on administrative units. This synthetic use of aggregating

administrative spatial units into neighbourhoods may not reflect how

respondents define their neighbourhood. It could be more meaningful to try to

find ways to improve the match. In future works, it is recommendable to

generate more urban form variables to find more built environment-related

significant variables. This was not done at a satisfactory level, due to

scarcity of resources and time.

In Europe and around the world,

research is being carried out into travel for work, services and entertainment

with results that may be surprising. The above research was conducted in

Kurdwanów and Piaski Północ districts. People met were asked

about things related to travel so that they could create a more accurate travel

model. In this study, we focused on non-work travel; these places are where

people go on the same road and therefore, have no alternative. When travelling

to services or entertainment, people have a choice of where, which way and how

to go. This study reveals that age, daily activity, place of shopping,

frequency of shopping near homes, and frequency shopping activities outside in

farther places significantly correlates with the frequency of non-work trips in

Cracow. Moreover, the availability of attractive shops is marginally

significant in the overall model. However, the differences made for the two

districts of different urban forms, show that the decentralised district of

Kurdwanów, which has several large residential buildings marked as

socialist urban form, produces more outbound non-work trips to other districts,

which may be more or less connected with higher levels of car use. This means

the more compact and central district of this study generates low outbound but

more domestic non-commute trips. The findings of this study suggest the

provision of more attractive shops and retail for keeping non-work urban

travellers, especially older ones, within the vicinity of their living place.

Implementing urban and spatial planning measures are suggested by this paper to

strengthen the concept of short distances within the city.

References

1.

„1935 –

Cracow's latest plan”. Available at: https://dawnemapyCracowa.pl/map/1935-najnowszy-plan-Cracowa/#15/50.0634/19.9450/1935_Cracow-osm_podklad_czb.

2.

Bhat Chandra. 1997. ,,Work Travel Mode Choice and Number of Non-Work Commute Stops”.

Researcher work. University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Department of Civil

and Environmental Engineering.

3.

bip.Cracow. „Comprehensive Traffic Research in

2013”. Available at:

https://www.bip.Cracow.pl/?sub_dok_id=96964&vReg=1.

4.

bip.Cracow. „Cracow in numbers

2017”. Available at:

https://www.bip.Cracow.pl/zalaczniki/dokumenty/n/215089/karta.

5.

Boarnet Marlon, Sharon Sarmiento. 1998. “Can

Land-use Policy Really Affect Travel Behaviour? A Study of the Link between Non-work

Travel and Land-use Characteristics”. Urban

Studies 35(7). DOI:10.1080/0042098984538.

6.

Cervero Robert. 2003. ,,The built

environment and travel: Evidence from the United States”. European Journal of

Transport and Infrastructure Research 3(2): 119-137.

7.

Churchamn Arza, 1999. ,,Disentangling the Concept of

Density”. Journal of Planning Literature 13(4): 389-411 DOI:

10.1177/08854129922092478.

8.

„Comprehensive Traffic Research in

Wrocław and the surrounding area 2018”. Available

at: https://www.wroclaw.pl/srodowisko/wyniki-kompleksowego-badania-ruchu-we-wroclawiu-i-aglomeracji-2018.

9.

„Cracow enlargement in 1941”. Available at: https://niemieckiCracowblog.wordpress.com/2017/03/30/rozszerzenie-Cracowa-w-1941-roku/.

10. „Cracow in 1891”. Available at: https://dawnemapyCracowa.pl/map/1891-Cracow/#15/50.0592/19.9409/1891_Cracow-osm_podklad_czb.

11.

Dumba Smart. 2017.

“Informal public transport driver behaviour and regulatory policy

linkage: An expose”. Journal of

Transport and Supply Chain Management 11(a315): 1:16. ISSN: 2310-8789.

12. Handy

Susan, Marlon Boarnet, Reid Ewing, Richard Killingsworth. 2002. “How

the butli environment affects physical activity: Views from urban

planning”. American Journal of

Preventive Medicine 23(2): 64-73. DOI: 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00475-0.

13. „How

Built Environment Affects Travel Behavior“. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280719159_How_Built_Environment_Affects_Travel_Behavior_A_Comparative_Analysis_of_the_Connections_between_Land_Use_and_Vehicle_Miles_Traveled_in_US_Cities.

14.

Jacyna M. 1998. “Some

aspects of multicriteria evaluation of traffic flow distribution in a

multimodal transport corridor”. Archives

of Transport 10(1-2): 37-52.

15.

„Plan of Cracowa and the

surrounding area during the Four-Year Sejm”. Available at: https://dawnemapyCracowa.pl/map/1788-plan-miasta-Cracowa-i-okolic-w-dobie-sejmu-czteroletniego/#14/50.0682/19.9422/1788_Cracow-osm_podklad_czb.

16. „Plan of Cracow T. Żebrawskiego”. Available at:

https://dawnemapyCracowa.pl/map/1866-plan-Cracowa-t-zebrawskiego/#14/50.0587/19.9430/1866_Cracow-osm_podklad_czb.

17.

Rostafiński Józef. 1891. Guide to Cracow and surroundings. Cracow: University

Printing House.

18.

Schmidt Marie, Stefan Voss.

2017. „Advanced systems in public transport”. Public Transport 9(1-2) Special Issue: 3-6. ISSN: 1866-749X.

19.

Silver S.D. 2018. „Multivariate methodology for

discriminating market segments in urban commuting”. Public Transport 10(1): 63-89. ISSN: 1866-749X.

20. Szarata A. 2014.

„Comprehensive travel survey in Krakow – chosen results”. Logistyka 6: 13798-13805.

21. „The Warsaw

Traffic Study 2015 together with the development of the traffic model. Report

from stage III. Development of research results”. Available at:

http://transport.um.warszawa.pl/sites/default/files/WBR%202015.%20Etap%20III.%20Raport.%20Wersja%2006_2016.pdf.

22. „The Warsaw Traffic Study in 2015 along with the development of a

traffic model. Synthesis”. Available at: http://transport.um.warszawa.pl/sites/default/files/WBR%202015%20SYNTHESIS%20EN.pdf.

23.

Walters Jackie. 2014.

“Public transport policy implementation in South Africa: Quo

vadis?”. Journal of Transport and

Supply Chain Management 8(a134): 1:16. . ISSN: 2310-8789.

24. „Wroclaw Traffic Research 2010”. Available

at:

http://www.transportation.overview.pwr.edu.pl/UPLOAD/BAZA-ARTYKULOW/PL/2011/07/A_PL_11_07_02.pdf.

Received 18.10.2019; accepted in revised form 29.12.2019

![]()

Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License