Article

citation information:

Mindur,

L. The impact of India’s economy on the

development of seaports. Scientific Journal of Silesian University of

Technology. Series Transport. 2019, 105,

169-182. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2019.105.14.

Leszek

MINDUR[1]

THE

IMPACT OF INDIA’S ECONOMY ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF SEAPORTS

Summary. India’s diversified economy includes

traditional and modern agriculture, crafts, modern industries and a variety of

services. In 2017, almost half (48.93%) of India’s GDP was generated by

the service sector, whereas the industrial sector accounted for 26.16% and

agriculture 15.45%. Despite a short-term economic downturn caused by a

demonetisation and implementation of compulsory tax on goods and services, the

continued favourable economic growth, including sustainable growth of the gross

domestic product, revenue per capita, private consumption and public

investment, as well as the improvement of other economic indicators, for

example, car sales indicate that India’s macroeconomic conditions are

generally stable. Structural reforms introduced by the government contribute to

enhanced productivity among domestic businesses and attract more foreign direct

investment. Due to its geographical location, India has been using sea

transport to promote its international trade. However, with too few deep-sea

ports and limited cargo handling capacity, its seaports can handle only some of

the largest intercontinental ships. This article discusses India’s

economic situation, with particular regard to the GDP growth in 2000-2017 and

foreign trade. The analysis covers growth in cargo handling in main ports in

India in 2000-2018. It discusses the port development project of Sagarmala

introduced by the Government of India in 2015. The project is expected to solve

problems associated with the performance of Indian ports and strengthen the

Indian maritime sector to meet the ever-growing demand for goods transported by

sea.

Keywords: India, main ports,

economy, cargo handling, Sagarmala

1. INTRODUCTION

India belongs to the

fastest growing economies and is currently the seventh largest economy in the

world. After the completion of reforms

liberalising the economy in 1991, India became one of the newly industrialised

countries. The economic growth has been accelerated by the deregulation

of industry, privatisation of state enterprises and the relaxation of foreign

trade and investment controls. The overall development of the country is still

undermined by corruption, poorly developed infrastructure, restrictive and

burdensome regulatory environment, as well as inefficient budget and finance

management[2].

The transport sector in India is large and diverse but it has been

lagging behind growing demands. Main directions for the development of the

sector set by the government are intended to support the further economic

growth of the country and eradicate poverty. Due to its geographical location,

India uses sea transport to promote its international trade; it accounts for approximately 95% of trade in goods in

terms of volume and 70% in terms of value[3]. However, infrastructure

in India’s seaports cannot compete with technologically advanced seaports

of China or Singapore designed to handle the largest container vessels in the

world. Guided by its economic calculations and geostrategic location, the

government of India has decided to introduce port development programs, create

transport corridors and modernise its logistics. The implementation of the

far-reaching large scale investment is designed to convert India into a global

production hub and boost its economy.

2.

INDIA’S ECONOMY

For the past several

years, India witnessed an accelerated growth regarding its gross domestic product of approximately 7% a year. As

regards GDP per capita, according to the International Monetary Fund, India was

ranked 119 out of 185 countries around the world in 2018, with its revenue per

capita of approximately 2,000 USD (for comparison, China was ranked 73)[4].

The diversified economy

of India consists of traditional and modern agriculture, crafts, modern

industries and a variety of services. In 2017,

almost half of India’s GDP (48.93%) was generated by the service

sector, whereas the industrial sector accounted for 26.16% and agriculture

15.45%. Leading service industries include telecommunications, IT and software.

The developing IT industry is gradually becoming

a very important part of India’s economy since, in the fiscal year of

2016/2017, it accounted for around 8% of the GDP, which was a slight decrease

in relation to previous years when the sector delivered approximately 10% of

GDP. Nevertheless, the IT industry has been steadily growing in terms of income

and employment. IT includes software development, consulting, software

management, online services and business process management (BPM)[5].

Fig. 1. India’s

GDP growth in 2000-2017

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ny.gdp.mktp.kd.zg?locations=in

India’s

economy is largely based on domestic trade and to a limited extent on export.

Therefore,

it remains less susceptible to external factors compared to other markets which

rely on foreign trade, particularly considering the current trade conflict with

the United States. India’s major trading partners include China, the

United States, United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, South Korea,

United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Germany.

In

2018, India exported goods worth 323.1 billion USD, which accounts for 19.1% of

its total GDP and growth by 8.4% compared to 2017. In terms of transaction

value, almost half of Indian goods (49.3%) were delivered to other Asian

countries, 19.3% to Europe, 18% to North America, 8.3% to Africa, 2.9% to Latin

America and the Caribbean (excluding Mexico) and 1.3% to Australia and Oceania[6].

The

2018 India’s import was worth 507.6 billion USD. The majority of goods

(60.3%) were brought from Asian countries. Goods purchased by India from their

European trading partners accounted for 15.8% of import, from Africa 8.2% and

from North America the remaining 8.1%. A less important contribution to the

overall imports was made by goods imported from Latin America and the

Caribbean, excluding Mexico (4.2%), and from Australia and Oceania (2.9%).

Product groups in Table

2 account for 80% of the total value of imports.

India has used its

large, educated and English speaking community to export its IT and business

services and promote the employment of its software programmers in foreign

companies[7]. However, the country still has one of the highest levels of poverty,

the largest income disparities and poorly developed public healthcare.

Fig. 2. Value of

India’s exports in 2007-2018, in billion USD

Source: own material

based on http://www.intracen.org/itc/market-info-tools/statistics-export-country-product/

Tab. 1

Individual product

groups in the total exports of India in 2018

|

Product Group |

Value, billion USD |

% of total exports |

|

Mineral fuels,

including oil |

48,3 |

14,9 |

|

Gems, precious metals |

40,1 |

12,4 |

|

Machines, including

computers |

20,4 |

6,3 |

|

Vehicles |

18,2 |

5,6 |

|

Organic chemicals |

17,7 |

5,5 |

|

Pharmaceuticals |

14,3 |

4,4 |

|

Electrical machines,

equipment |

11,8 |

3,6 |

|

Iron, steel |

10,0 |

3,1 |

|

Cotton |

8,1 |

2,5 |

|

Clothing, accessories

(excl. knitting) |

8,1 |

2,5 |

Source: http://www.worldstopexports.com/indias-top-10-exports/

Fig. 3. Value of

India’s exports in 2007-2018, in billion USD

Source: based on

http://www.intracen.org/itc/market-info-tools/statistics-export-country-product/

Tab. 2

Individual product

groups in total imports of India in 2018

|

Product Group |

Value, billion USD |

% of total imports |

|

Mineral fuels,

including oil |

168,6 |

33,2 |

|

Gems, precious metals |

65,0 |

12,8 |

|

Electrical machines,

equipment |

52,4 |

10,3 |

|

Machines, including

computers |

43,2 |

8,5 |

|

Organic chemicals |

22,6 |

4,4 |

|

Plastics and products |

15,2 |

3,0 |

|

Iron, steel |

12,0 |

2,4 |

|

Animal fats/vegetable

oils, wax |

10,2 |

2,0 |

|

Optical, technical and

medical devices |

9,5 |

1,9 |

|

Inorganic chemicals |

7,3 |

1,4 |

Source:

http://www.worldstopexports.com/indias-top-10-exports/

India

is the second after China in the world in terms of its population. In 2017, the

population was nearly 1.4 billion people[8]. To meet their demand

for employment in the working-age population, each year more than 10 million

jobs should be created.

The structure of the Indian labour market distinguishes

between employment in informal and formal sectors. The informal sector employs

almost 81% of all the employed in India, whereas the formal only 6.5% and 0.8%

in the household sector[9]. The informal sector includes companies

operating on their own account. These include all unlicensed, single person or

unregistered businesses, such as shops, crafts, physical work, rural trade,

agriculture, etc. The organised sector includes people

employed by the government, state enterprises and enterprises of the private

sector. These include businesses that are registered and subject to tax on

goods and services, such as banks, private schools, hospitals, listed

companies, corporations, factories, shopping centres, hotels, etc.

For several years, India

did not publish its employment figures (last official data are of 2012 - then

unemployment rate was 2.7%). However, independent experts estimate that in the

last period, the unemployment rate has been growing at the highest rate in the past

45 years and it is now 8.5% (in 2018 alone, India lost 11 million jobs), and

the rapid economic growth generates much fewer jobs than in the past[10].

Despite a short-term

economic downturn caused by demonetisation

and implementation of compulsory tax on goods and services, the continued favourable economic growth, including sustainable growth of the

gross domestic product, revenue per capita, private consumption and public

investment, as well as the improvement of other economic indicators, for example, car sales, indicate that India’s

macroeconomic conditions are generally stable. Structural reforms introduced by

the government contribute to enhanced productivity among domestic businesses

and attract more foreign direct investment.

In 2014, the Indian government

implemented the „Make in India” program, which is intended to

transform India into a global production hub, contributing to the creation of

new jobs and

the rise of the professional qualifications

of the population. The initiative has been gradually gaining momentum and would benefit various sectors, including the maritime

economy.

3. SEAPORTS IN INDIA

The

Indian peninsula has one of the largest coastlines in the world, extending a

distance of more than 7500 km, with approximately 200 seaports of India,

including 12 major ones. The main

ports handle more than 75% of the total freight traffic[11]. On

the east coast, India has the following main ports: Calcutta (Kolkata Dock

System and Haldia Dock Complex), Paradip Vishakhapatnam, Ennore, Chennai, Chidambaranar (formerly Tuticorin),

whereas on the west coast: Kochi, New Mangalore, Marmagoa, Mumbai, Jawaharlal

Nehru (JNPT) and Kandla. The main ports are answerable to the Ministry of

Shipping except

for the port of Ennore, which is a public company acting under the business

name of Kamarajar Port Limited registered as a company (68% of shares owned by

the state and 32% by Chennai Port Trust), and the company pays dividends to the

state[12]. Smaller ports are answerable to governments of

relevant states and perform the role of auxiliary ports for the above

mentioned main ports.

Fig. 4. Main and

auxiliary seaports of India

Source: https://www.mapsofindia.com/maps/sea-ports/

2000-2018

cargo handling in major ports of India is shown in Table 3.

Tab. 3

2000-2018

cargo handling in ports of India, in thousand tons

|

Port |

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|

Calcutta |

31 001 |

46 207 |

46 423 |

47 545 |

43 248 |

39 928 |

41 385 |

46 292 |

50 289 |

50 951 |

57 886 |

|

Paradip |

13 636 |

55 801 |

57 011 |

56 030 |

54 254 |

56 552 |

68 003 |

71 011 |

776 386 |

88 955 |

102 013 |

|

Vishakhapatnam |

39 510 |

50 147 |

65 501 |

68 041 |

67 420 |

59 040 |

58 503 |

58 004 |

57 033 |

61 020 |

63 537 |

|

Ennroe* |

- |

9479 |

10 703 |

11 009 |

14 956 |

17 885 |

27 337 |

30 251 |

32 206 |

30 020 |

30 446 |

|

Chennai |

37 443 |

43 806 |

61 057 |

61 460 |

55 707 |

53 404 |

51 105 |

52 541 |

50 058 |

50 214 |

51 881 |

|

Chidambaranar |

9993 |

15 811 |

23 787 |

25 727 |

28 105 |

28 260 |

28 642 |

32 414 |

36 849 |

38 463 |

36 583 |

|

Kochi |

12 797 |

14 095 |

17 429 |

17 873 |

20 091 |

19 845 |

20 887 |

21 595 |

22 098 |

25 007 |

29 138 |

|

New Mangalore |

17 600 |

33 891 |

35 528 |

31 550 |

32 941 |

37 036 |

39 365 |

36 566 |

35 582 |

39 945 |

42 055 |

|

Marmagoa |

18 226 |

30 659 |

48 847 |

50 022 |

39 001 |

17 693 |

11 739 |

14 711 |

20 776 |

33 181 |

26 897 |

|

Mumbai |

30 384 |

35 187 |

54 541 |

54 586 |

56 186 |

58 038 |

59 184 |

61 660 |

61 110 |

63 049 |

62 828 |

|

JNPT |

14 976 |

32 808 |

60 763 |

64 309 |

65 727 |

64 490 |

62 333 |

63 802 |

64 027 |

62 151 |

66 004 |

|

Kandla |

46 303 |

41 551 |

79 500 |

81 880 |

82 501 |

93 619 |

87 004 |

92 497 |

100 051 |

105 442 |

110 099 |

|

Total |

271 869 |

383 745 |

561 090 |

570 032 |

560 137 |

545 790 |

555 487 |

581 344 |

606 465 |

648 398 |

679 367 |

*Lawful operations started in

December 2002

Source: own material based on http://www.ipa.nic.in/index1.cshtml?lsid=155

The busiest ports handling the

international container traffic include Calcutta, Chidambaranar, Chennai, Cochin, Vishakhapatnam and Jawaharlal

Nehru

(Table 4).

Tab. 4

2000-2017

container handling in the largest ports of India, in thousand TEU

|

Port |

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

|

Calcutta and Haldia |

175 |

287 |

502 |

526 |

552 |

600 |

563 |

630 |

663 |

772 |

|

Chidambaranar (Tuticorin) |

137 |

307 |

440 |

468 |

477 |

476 |

508 |

560 |

612 |

642 |

|

Chennai |

322 |

617 |

1216 |

1524 |

1558 |

1540 |

1468 |

1552 |

1565 |

1495 |

|

Cochin |

130 |

185 |

290 |

290 |

336 |

335 |

347 |

366 |

419 |

491 |

|

Vishakhapatnam |

20 |

45 |

98 |

145 |

234 |

247 |

262 |

248 |

293 |

367 |

|

JNPT |

889 |

2371 |

4062 |

4270 |

4321 |

4259 |

4162 |

4467 |

4492 |

4500 |

|

Total |

1673 |

3812 |

6608 |

7223 |

7478 |

7457 |

7310 |

7813 |

8044 |

8267 |

Source: own material based on http://www.ipa.nic.in/index1.cshtml?lsid=155

The analysis of

2000-2018 cargo handling changes in major ports of India indicates a steady

increase. A visible slowdown in 2012-2014 resulted from the reduction in trade

after the world economic crisis, as well as the insufficient capacity of

infrastructure in Indian ports and weak operating results due to the limited

possibility of further shipments[13]. Apart from

insufficient capacity, the development of Indian ports can be seen as a key

factor in the protection of the Indian trade against fluctuations in the global economy. However, too few deep-sea

ports and limited cargo handling capacity constrains its seaports handling of

only some of the largest intercontinental ships. As a result, much Indian cargo

must be reloaded in more developed Asian ports (Colombo, Sri Lanka), which

increases time and cost of operation[14]. For example,

one-quarter of containers which in 2016 were handled by the main state ports of

India had to be transshipped elsewhere[15]. To resolve these

issues and to strengthen the Indian maritime sector in the context of the

ever-growing demand for goods transported by sea,

in 2015, the government of India adopted a port development project known as

Sagarmala[16]. Its goal is to deliver

a comprehensive solution to problems faced by the Indian ports.

4. THE SAGARMALA STRATEGY FOR DEVELOPMENT OF SEA PORTS

The Sagarmala Strategy

has been developed as part of a broader program of “Make in India”

as its key component. The coordination of the program at the national level is

the responsibility of the Ministry of Shipping, which take care of the

transformation of infrastructure into a modern system. The process comprises

the modernisation of ports and their integration with special economic zones,

smart port cities, industrial parks, warehouses, logistics parks and transport

corridors. According to the plan, the implementation of the project should attract foreign direct investment and the implementation of individual projects under the

Sagarmala Strategy (mainly private or PPP schemes) and their consistency is the

responsibility of respective ports, state governments/maritime councils, and

central administration.

The

concept of "port-driven development” is the heart of the Sagarmala

vision. The concept focuses on intensive development of logistics supported by

efficient and modern port infrastructure and a functioning supply chain

supported by qualified personnel.

As regards the above

assumptions (upgrade of existing ports and development of new ones, improvement

of connections to ports, industrialisation of ports and development of coastal

communities), the program identifies 415 projects, the implementation of which

is staged in 2015-2025 with the expected

cost of 123 billion US dollars [17].

The Government of India believes that the implementation of the Sagarmala Strategy will reduce the costs of logistics, which is crucial for domestic production. Today, in India, the logistics cost

consumes about 19% of GDP (1/3 higher than in China), to compete on the global

market, India needs to reduce it to 4-6%[18].

According to the National Plan, the

Sagarmala Strategy provides

for[19]:

-

Modernisation

of existing and development of new ports -

through 189 projects, including 116 to improve the operational capacity of the

existing ports and the construction of six

mega-ports: Vizhinjam International Seaport (status Kerala), Colachel Seaport

(Tamil Nadu) Vadhavan Port (Maharashtra), Tadadi Port (Karnataka),

Machilipatnam Port (Andhra Pradesh) and Sagar Island Port (West Bengal).

The country designated a total of 21 billion USD for the above objectives. The

implementation of the Vizhinjam port project is underway and projects in other

ports are in the designing phase;

-

Improvements

in communication with ports - 170

projects with the expected cost of 35 billion US dollars to modernise road and

railway infrastructure and building multimodal hubs on 111 inland waterways in

24 states; a number of inland waterways will gain national status, which means

that they will be included in the development program. This group of activities

includes such governmental projects as Jal Margin Vikas (four terminal ports on

River Ganga). India contracted a loan from the World Bank in the amount of 375

million US dollars for the project[20], Dedicated Freight Corridors

(construction of rail corridors that can handle

longer and heavier freight trains from/to ports in Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and

Kolkata and diagonal corridors north-south Delhi-Chennai and east-west

Calcutta-Mumbai) Whether Bharatmala (construction and upgrading of 34

800 national roads, including 2000 km of roads along coastlines and in major

ports);

-

Industrialisation

associated with ports - 33 projects of the expected cost of 65 billion USD. The

initiative provides for the development of economic regions (CEZ) in

14 coastal zones with industrial clusters. The objective is to save time and

reduce costs of cargo handling in national and international traffic. It is

estimated that in coastal zones, direct and indirect employment may reach 6

million people. Energy clusters, consisting of refineries and petrochemical

industry, reduce India’s dependence on import of petroleum products. By

2025, two more refineries and four petrochemical clusters located along the

coast of India should be developed;

-

The

development of coastal communities - the cost of 23 projects promoting the

involvement of people living in coastal zones (18% of India’s population)

in the overall socio-economic development of the region is 648 million USD.

Projects focus on education of citizens, development of refrigeration chain,

fisheries, aquaculture, local tourism and leisure facilities.

At the

same time, it is expected that the implementation of the Sagarmala strategy will

contribute to the annual reduction of CO2 emission from transport by

12.5 MT.

In March 2018, in the

different phases of development and implementation were 492 projects worth 62

billion USD[21]. Out of the total 116

investment projects improving the operational efficiency of major ports, 91

projects have been completed, 8 are in progress, and 9 projects abandoned[22].

Noteworthy is the

building of the new container port of Vizhinjam, Kerali State, launched in 2019

at the coast of Arabian Sea under the PPP scheme. It is going to be the first

in India deep-sea mega-terminal (up to 18 m

draft) capable of handling the largest container vessels of up to 24 thousand

TEU. In addition to the port of Dhamra, which does not yet have an adequate

infrastructure to handle container ships, no other Indian container port has

such operating depth[23].

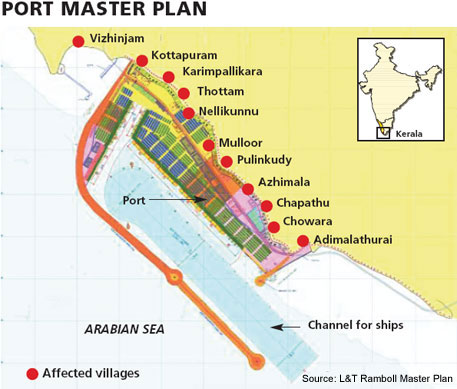

Fig. 5. Masterplan for

Vizhinjam Seaport

Source: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/tag/vizhinjam

The building of the Vizhinjam seaport, including the breakwater, quays, terminal and the port

building, is divided into three stages. Stage one, requiring dredging at sea,

includes the construction of an embankment of 66 ha and a breakwater of 3180 m

in length. The project also includes a railway line of 10.9 km and a 9

km tunnel (second longest railway tunnel in India) to connect the port and the

main railway line[24]. The port is expected to be put into service at the end of 2020. According

to the agreement, the port will be operated by Adani Vizhinjam Port (AVPL), a

private concessionaire, for 40 years with the possibility to extend the

contract for further 20 years, whereas the state government will receive part

of the revenue after 15 years.

5. SUMMARY

In

India, the establishment of new ports and modernisation of existing ones, development of

coastal zones, improved transportation between ports by expanding road, rail

and inland waterways networks and the development of multimodal logistics parks

will boost economic development in coastal areas and stimulate the development

of the whole country, creating new jobs.

An efficient system of

connections to ports in India is very important because centres attracting

goods for shipment are mainly located inland rather than in coastal regions. A

long distance to the destination point of the shipment increases the logistics

cost and time for cargo to be delivered. Connectivity between ports of India

with their hinterland is based primarily on road and rail transport, whereas

coastal and inland waterway shipping plays a very limited role. Hence, the

creation of a well-connected logistics system in the country together with the

introduction of new technologies and increasing handling capacity of ports is

of paramount importance for the development of the national economy. This is

one of the major factors boosting competitiveness, promoting traffic flow in

the ports of both at the present and expected increased levels resulting from

the development of international trade in goods.

For the main ports of

India to be globally competitive, the Member State must ensure an attractive investment climate for global investors.

In the framework of projects related to the

construction and development of ports, the government of India has permitted

direct foreign investments up to 100% of their value. In the period from April

2000 to December 2018, the port sector in India attracted aggregated direct

foreign investment of 1.64 billion USD. Moreover, companies investing may enjoy

10-year tax exemption and apply for financial aid of 50% of investment value.

Additionally, the 10-year tax exemption was extended to companies dealing with

development, maintenance and operation of sea and inland ports, as well as

inland waterways[25].

Indian

government plans to improve the efficiency of all 12 major port have been finalised. Projects concentrating on the

development of cargo handling capacity will be gradually implemented in the next 20 years. At the end of March

2018, in different phases of their development and implementation were 492

projects worth 62 billion USD[26].

References

1.

2019 Index of Economic Freedom. Available

at: https://www.heritage.org/index/country/india.

2.

Berry A. 2018. Ports in India Need

Overhaul. The Economic Times. Available at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/transportation/shipping-/-transport/ports-in-india-need-overhaul-agam-berry-quantified-commerce/articleshow/63886226.cms.

3.

CNN Business. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2019/04/05/economy/narendra-modi-economy-election-india/index.html.

4.

Developing Ports: Sagarmala Project.

Available at: http://www.makeinindia.com/article/-/v/developing-ports-sagarmala-project.

5.

DownToEarth.

Available at: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/tag/vizhinjam.

6.

Financial

Times: India’s new private ports

challenge ageing state giants. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/b6892980-2e68-11e7-9555-23ef563ecf9a.

7.

GKTODAY, GK-Current Affairs_General

Studies. Available at: https://currentaffairs.gktoday.in/tags/jal-marg-vikas-project.

8.

Government of India, Ministry of Finance.

2018. Sagarmala: Background. Available at: http://sagarmala.gov.in/about-sagarmala/background.

9.

IBEF. Available at: https://www.ibef.org/industry/indian-ports-analysis-presentation.

10.

India Brand Equity Foundation. Available

at: https://www.ibef.org/industry/ports-india-shipping.aspx.

11.

India Briefing. Available at: https://www.india-briefing.com/news/sagarmala-developing-india-ports-aid-economic-growth12980-12980.html/.

12. India: Government to Build Mega Container Terminal at Chennai. DredgingToday.com.

October 2011.

13.

Indian Ports

Association. Available at: https://www.ipa.nic.in/index1.cshtml?lsid=155.

14.

International

Trade Centre. Available at:

https://www.intracen.org/itc/market-info-tools/statistics-export-country-product/.

15.

Make in India. Available at: https://www.makeinindia.com/article/-/v/developing-ports-sagarmala-project.

16.

Maps od

India. Available at: https://www.mapsofindia.com/maps/sea-ports/.

17.

Mindur L. (Ed.). 2014. Technologie transportowe. [In Polish: Transport technologies]. Radom: ITE-PIB.

18.

Mindur M. 2009. Transport

Europa-Azja. [In Polish: Europe-Asia

transport]. Radom: ITE-PIB.

19. Mindur M. 2010. Transport w erze globalizacji. [In Polish:

Transport in the age of globalization]. Radom: ITE-PIB.

20.

Mishra

D. Sagarmala – Transformation of the Maritime

Infrastructure and Make in India. April 2018. Available

at: https://medium.com/@devsenamishra/sagarmala-transformation-of-the-maritime-infrastructure-and-make-in-india-4ba48ec0c80b

21.

The

World Bank. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ny.gdp.mktp.kd.zg?locations=in.

22.

Sagarmala. Available at: http://sagarmala.gov.in/project/port-modernization-new-port-development.

23.

Seanews. Available at: https://seanews.co.uk/features/container-shipping-indian-ports-set-to-outpace-previous-records/.

24. Mindur M. (Ed.). 2017. Logistyka. Nauka-Badania-Rozwój

[In Polish: Logistics. Science-Research-Development].

Radom: ITE-PIB.

25.

.Obed Ndikom, Nwokedi Theophilus C.,

Sodiq Olusegun Buhari. 2017. “An appraisal of demurrage policies and

charges of maritime operators in nigerian seaport terminals: the shipping

industry and economic implications”. Naše

More 64(3): 90-99.

26.

Ojadi Francis, Jackie Walters 2015.

“Critical factors that impact on the efficiency of the Lagos seaports”.

Journal of Transport and Supply Chain

Management 9(a180): 1:13. ISSN:

2310-8789.

27.

Poonawalla S., R. Sinha. Will Vizhinjam port fulfill India's maritime

dream? Rediff Business. December 2015. Available at: https://www.rediff.com/business/column/will-vizhinjam-port-fulfill-indias-maritime-dream/20151214.htm.

28.

Statista. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/271329/distribution-of-gross-domestic-product-gdp-across-economic-sectors-in-india/.

29.

The News Minute. Available at: https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/kerala-s-vizhinjam-port-commissioning-deadline-extended-october-2020-96738.

30.

The WIRE: Nearly 81% of the Employed in India Are in the Informal

Sector: ILO, maj 2018. Available at: https://thewire.in/labour/nearly-81-of-the-employed-in-india-are-in-the-informal-sector-ilo.

31.

The World Bank. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/country/india.

32.

World Economic Outlook Database. April

2019. International Monetary Fund. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?sy=2018.

33.

World’s Top Exports. Available

at: https://www.worldstopexports.com/indias-top-10-exports/.

Received 11.09.2019; accepted in revised form 02.11.2019

![]()

Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License