Article

citation information:

Kunert, O. How not to lose valuable

know-how in an industry? Scientific Journal of Silesian

University of Technology. Series Transport. 2019, 105, 125-137. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2019.105.11.

Olimpia

KUNERT[1]

HOW NOT

TO LOSE VALUABLE KNOW-HOW IN AN INDUSTRY?

Summary. Know-how belongs to the intangible assets of

enterprises. They are defined as information consisting of verified in practice

technical knowledge and skills in goods trade (which are not covered by

patents) allowing the entrepreneur to achieve a competitive advantage.

Intangible assets are currently the key resource of enterprises, within which

innovative competencies are included. They are not visible in the balance

sheets of companies, they do not grow in proportion to property investments and

do not yield to ownership. They have a spatial dimension of a special

character, and they create the intellectual capital of the organisation, which

along with the acquired knowledge, using active growth factors, can gain the

ability to process innovations and act towards the development of the

organisation. However, this is not always the case, hence, the attempt to

answer the question of how not to lose valuable know-how in an industry. The

conducted surveys among enterprises providing services for the industry have

shown that they have innovative potential. This means that not only the

industry and its development may affect the service sector and its performance,

but the reverse - the service sector may influence the demand of the industrial

sector. The article presents the potential for innovation growth with the

employees’ own knowledge.

Keywords: industrial enterprises,

know-how, acquisition and loss of knowledge

1. INTRODUCTION

Forecasts for the future indicates

the decline of production in the traditional form. The increase in the share of

services provided to industries is a determinant of changes in the industry.

This process does not proceed in a uniform manner; some industrial functions

based on outsourcing, are adopted from industrial enterprises to the service

sector or industrial related services remain in the industrial sector, as activities provided by a service

entity linked by capital or provided by employees. Such a limitation of

strictly production activities and a statistically visible increase in services

in the industrial sector, however, does not entail any increase in market

competitiveness as if it were done in the case of services provided by external

entities. There are benefits here, which lead to an improvement in the

allocation of resources and the possibility of achieving profit specialisation

and they result from changes in the value chains of industries and services (in

industry reduction and in services growth of value chain), considered by

industries, show economic benefits from the scale of outsourcing [4].

Globalisation has created many

conditions, including for industry products. Currently, industries require much

more services than several years ago and this trend is still growing. Global competition means, among other

things, offering the best product or service at the lowest price [8]. As a

result, the quest for ways to reduce costs leads to business mergers or

closures of companies, and mergers of companies resulting in the emergence of

enterprises that seek to dominate on a global scale. All forms of mergers bring

redundancies as well as changes in the labour market.

A deeper analysis of the mutual

relations between industries and services, which goes beyond the statistical

data on employment and value-added services, makes it possible to recognise

from the point of view of industrial development that the industry sector is

more important for the service sector or inversely. This type of extended analysis

also shows the area of so-called “Related services”, that is,

services for which demand increases appear as a result of increased demand from

the side of the industry. There are intensified interactions in the area of

“related services”, industry for the development of the services

sector and the simultaneous impact of the services sector on the productivity

of the industrial sector. Moreover, we not only observe an increase in the

demand for services related to the production industry but mainly the growing

interdependence of industries with service companies. It means within the

sectoral integration of production and services, which in consequence results

in the growth of intersectoral links (industries and services) and the

development of new organisational forms in industries.

Linking services to industries can

be understood in two ways. The first method comes from the industry specified

in the official statistics for which its services are defined. In this case,

the services also include related companies. However, the problem is that the

services are provided to other service providers who are often industrial

enterprises. It is difficult then to distinguish which services depend on the

demand for manufacturing companies and which do not. The second problem is the

criterion for the division into services related to a specific industry and to

the industry sector, in general. In this sense, an industrial enterprise that

in part of its process is included in the production process of another

industrial enterprise provides service around the industry, but official

statistics do not include this and both companies are included in the industry.

The second way to understand

industrial services is to perceive them as services provided by emerging

industrial enterprises in connection with the supply of industrial products to

other companies. This distinction concerns the development of cooperative

services in industrial enterprises, which distinguish this difference as a

product-service in their own reports as part of the industrial benefit.

The analysis of the process of

building innovative competencies of enterprises with any types of market

competences, which are often accompanied by the possession of specific

innovation potential, was carried out using the MeRKI-U method [1]. The

methodology refers to enterprises that can build their innovative competencies

from scratch, they can develop the already existing innovative potential, and

can also assess the impact of innovation potential or competences on the value

of the company.

The method has been verified in the

research project 4126/B/H03/2011/40 “Methodical basis for the dynamics of

development of industrial services in Poland for the purpose of merging the

European Union market”. The research subject was based on the analysis of

technological connections between the industry and the service sectors in

Poland, guaranteeing the development of industrial related services. For the

purposes of the integration of the industrial services market in the EU, it was

necessary to recognise whether the innovative domestic industry provides the

services sector with new technologies and knowledge, mainly through the supply

of intermediate products and the kind of absorption capacity the service sector

have in Poland.

The cooperators were identified in

ten selected branches of industry in terms of establishing the dynamics of

development of industrial services in Poland and the links between intermediate

products and services and the industry. The research concerned a representative

sample of 100 classified enterprises into 10 selected industries, that is,

mechanical, construction, textile, plastics, chemical, power energy and

electricity, cross-industry services, machinery, food, and paper and printing

industries. The survey was conducted in Poland, in the form of direct

interviews, using a questionnaire. These were mainly individual interviews with

the representatives of management boards and extended interviews with the

owners or co-owners of the surveyed enterprises, at their respective company

headquarters.

The surveyed enterprises varied in

size (small, medium, large), ownership relations (private, state treasury),

capital origin (Polish, foreign and mixed capital), industry and voivodeships.

The sector of small and medium enterprises was the dominant environment among

the surveyed enterprises, while large companies constituted the minority.

Small enterprises were dominated by

services provided for one industry (53%). Medium and large companies usually

provided services for two or three different industries. Services related to

the manufacturing process is foremost, product-related services came second;

the lowest percentage concerned the service industry. The structure shown is a

reflection of the current needs of the Polish industry, which in the context of

ownership changes resulting from privatisation, are characteristic of countries

after systemic transformation. The market of machine and equipment maintenance

services has been limited due to the introduction of internal servicing within

the corporate organisation. Other companies that have modernised the machine

park also make use of the maintenance service provided by suppliers, obligatory

during the warranty period and for the most part in the further period of

operation. Enterprises largely lost their machines and devices of the older

generation replacing them with modern machines, and thus, the market of

maintenance services changed. The maintenance services market is dynamic in

relation to domestic suppliers as it mostly concerns IT services, electric

motors, etc.

The majority of surveyed

enterprises (over 90%) are engaged in pro-innovation activities, both products

and processes.

This paper in its theoretical part

addresses the circle of scholars studying and describing the phenomena of

knowledge management. In the practical (research) part, it focuses on

specialists and managers professionally involved in the management of

corporations and enterprises, who often face the problem of assessing the value

of innovative enterprises in the perspective of increasing the company's value.

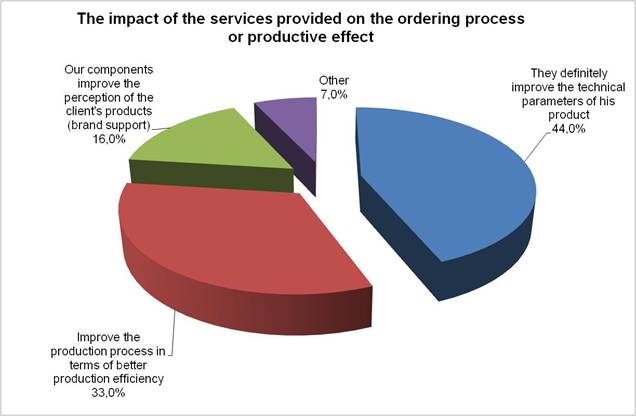

Fig. 1. The impact of the services provided on the

ordering process or productive effect Source: author

Fig. 1. The impact of the services provided on the

ordering process or productive effect Source: author

2. SERVICES DEVELOPMENT

ON A GLOBAL SCALE

In a direct way, industrial-related

services are part of industrial added value and they concern the production

process or the product itself. Services are understood as cooperation in the

process of making subassemblies, parts, elements and components or providing

production services in the scope of processing or refining of the products

ordered by contracting entities as part of the logistics supply chain. These

are often manufacturers executing orders from other manufacturers (as an

intermediate product) and contractual relationships between them. Indirect

production may be associated with the product - for example, packaging,

conditioning, completing, etc. or with the production process - components

included in another product ordered by its manufacturer, with specific

technical and operating parameters, moulds, specialist tools etc. made from own

or entrusted materials or services on entrusted materials.

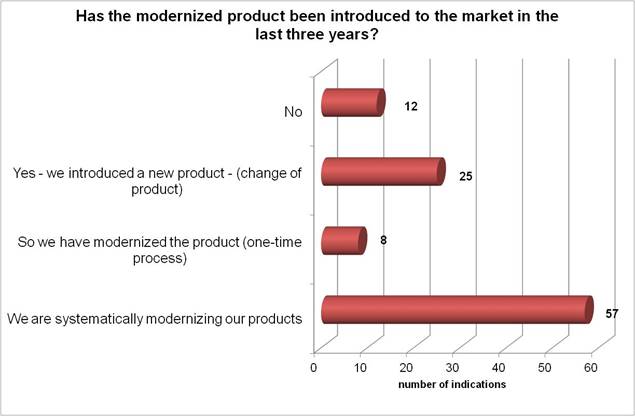

Fig. 2. Has the modernised product been introduced to

the market in the last three years?

Fig. 2. Has the modernised product been introduced to

the market in the last three years?

Source: author

The needs of services on a global scale

mean that their character has changed. The need for global communication,

transport, planning needs, market information, etc. is different today. This

change made it almost impossible to sell industrially produced devices or

products without additional services. Customers' expectations also concern

'pre-sales' and' after-sales' services.

The number of industrial products

is increasing, in which services cease to perform auxiliary functions and start

to play a major role, thus, contribute to the company's profit. This is the

case when the use of the product depends on the offer of services (service,

software, facilities, etc.). In some cases, the share of industrial services in

the value-added chain of producers exceeds even 50%. In many transactions of

investment property, lessors, maintenance service companies and companies

offering software are taking part simultaneously. Without their participation,

the sale of some products would be significantly hampered or even impossible.

This strong hybrid combination of goods with the existence of services has

created the concept of a “bundled product” – prearranged

combination of a given product with other services offered at an inclusive

price. In such cases, the definitions of industrial production and services are

blurred. An example could be the production of television sets, which would be

impossible to sell without access to television programs as complementary

services.

Industrial related services can be

classified differently, but two groups are visible from the point of view of a

close relationship with an industrial product. The first group of services is

to launch the product and enable it for usage. These are typically technical

services related to documentation, assembly, installation, maintenance, repairs,

training. The second group of industrial services includes the offer of

services that increase the value of an industrial product for the buyer, for

example, financing, insurance, service packages, etc. In this kind of

service-related products, the interaction between producers and customers is

usually higher than in the first group of products related to services. At the

same time, the flow of information from buyers to suppliers of this type of

services is particularly high, as financial service providers and insurers have

access to the specific field of the client's business. In this way, if

necessary, you can get data for managing customer relationships and

cross-selling of other goods or services that are offered by industrial

enterprises.

Sophisticated buyers can be

attracted and maintained only by the offer of newer and more innovative

products and services. It also requires focusing on the development of services

that are tailored to individual customer segments. In this context, it is very important

to exchange information with clients. This means that in the case of new

insights and changing customer needs, industrial enterprises with high

production flexibility can react quickly to the product. Therefore, it is not

surprising that the increasingly widespread use of information and

communication technologies in recent years has given a significant boost to the

development of products related to services.

Foreign direct investments in the

internal market are dominated by services. Given the fact that services also

control the European economy, the potential benefits of merging the service

market can be enormous. This explains the importance of the Services Directive

[3], which shows the full potential of the EU service sector. This potential, however,

is not fully used. The problem is that despite the possibility of increasing

foreign investment in services by 20-35%, the services market is not fully

regulated by law. National law can work in favour of domestic companies and at

the same time discriminating foreign companies. The lack of competition in the

financial services sector leads to the conclusion of unfavourable contracts by

customers: (high prices, less availability of credit). It is estimated that

existing barriers to foreign companies in the financial sector caused an

increase in prices by an average of 5.3% in 2005. The elimination of such

barriers would increase wages and salaries throughout the EU by 0.4% on average

and increase employment by 0.3%. In addition, with a merged market, there is

potential for an increase in European trade by 15-30%.

Foreign investments within the

EU-15 are focused on the service sector. In general, the share of foreign

investment in services is three times higher than in production; (in 2002, the

share of services was eight times greater). European companies put services

overproduction like in other regions of the world, but significantly less than

in Europe.

German research on the determinants

of the expansion of services related to industries has shown great determinants

in the development of industries and industrial services [5]. Germany has a

competitive advantage mainly in the production of high-tech equipment, but the

high export rate also applies to pharmaceutical firms, chemical companies,

machinery industry and transport as well. In comparison with the rest of the

production, they show a high level of growth in demand for services. This

sub-sector represents a demand factor of exceptional importance and shows the

highest expenditure on development and innovation.

3. INNOVATION OF THE

INDUSTRIAL RELATED SERVICE SECTOR

The challenge for the scientific

world in Poland is to develop a knowledge-based economy faster than other

countries do. The partners in this matter are enterprises that need to invest

in innovation to participate more in international markets. According to IFW [6],

the decisive factors for successful management results are innovations and the

process of disseminating it. Innovation is the ability to develop and implement

new solutions, both technological and organisational, which affects the

competitiveness of enterprises and other organisations.

In an innovative process consisting

of many stages, the most important issue is the organisation’s ability to

transform innovation for its own use. This ability is called innovative

competence. Intangible assets are currently the key resource of the

organisation, within which innovative competencies are included.

The most significant are changes in

the way the information is being used and how much the perception of its value

has evolved lately. Nowadays, information has become a source of wealth and

career. These changes can be observed in the whole economy. Even those

entrepreneurs who operate on the market in a traditional way now use electronic

devices and way of obtaining information and communicating with the environment

and employees. This means that intangible resources, not material as formerly

held have become a source of economic value. Affluence is determined by

knowledge, inventions and intellectual property.

We have entered the era of

information with all its consequences in terms of methods of obtaining

information, its processing speed and value for creating profit. Enterprises

today have smooth organisational structures and multidimensional networks of

informal relationships based on intellectual values of employees.

Qualifications, know-how and specialist knowledge of co-workers have an

increasing impact on the strategic success of the company. At the same time,

faster technological development means that the distance to the once acquired

knowledge is on the decline, hence, the need for more investment in the most

important factor of success: company’s know-how.

The organisation of the virtual

environment and tools is not hierarchical; it does not have structural

characteristics in the traditional sense but ensures the relative stability of

the organisation of this virtual background. This is due to the “IT core”,

which is distributed horizontally in the form of a network (Fig. 3) and it is

expected to be a strong structure that can carry significant loads.

The electronic economy based on IT

features means that it is possible to achieve huge economic effects in the new

conditions of communication and cooperation, but at the same time, changes can

be observed in the old ways of doing business. The market of an IT-based

economy is not divided; you can make transactions of material, financial and

intellectual property. The present-day local entrepreneur who exists in virtual

reality has access to the global market.

Tracking the achievements of

Scania, which has increased the number of alliances in five years with a

virtual crew scattered around the world, it has been demonstrated that human

capital is decisive in the knowledge age and that intellectual capital is

crucial to the long-term success of the organisation.

Intangible resources include assets

and competencies [7]:

·

the

assets are determined by such elements as patents, trademarks, brand names,

copyrights, databases, contracts concluded, commercial contracts and company's

reputation,

·

competences

are determined by knowledge and skills of staff and employees, ability to learn

and implement changes, and organisational culture.

Competence Management

(Fig. 4) is an organised, methodical activity conducted by the organisation by

performing the following functions:

·

determining

the competencies necessary for individual positions,

·

determining

the employees’ individual competences,

·

determining

the possibilities, interests and preferences of managers and employees in terms

of the development of their competences,

·

determining

missing competencies in relation to job requirements,

·

undertaking

a set of activities in order to complete missing competences,

·

substantive

and psychological preparation of managers and employees to function in the

changing conditions in order to meet the company’s development needs.

Fig. 3. The external environment of the enterprise, taking into account

the virtual environment

Source: author

4. SILENT KNOWLEDGE OF

EMPLOYEES

Research has shown that apart from

knowledge undergoing management processes, there is also a significant area of

“hidden” knowledge, which remains largely unused by the enterprise.

This is the employees’ own knowledge (Fig. 5), which under certain

conditions can be obtained or lost by the company.

The management, manufacturing and

information processing system were analysed. In the process of each of the

above-mentioned systems, there were two types of existing knowledge, that is,

employee's own knowledge and documented knowledge as well as knowledge kept by

the employee who does not share his knowledge or skills with his employer.

Extended studies of this last type of knowledge allowed to estimate the balance

of loss and acquisition of employee’s own knowledge (Fig. 5).

This part of employees' specific

knowledge was analysed in the three systems mentioned above and in two other

significant areas in which the company's management system has significant

impact, particularly during recruitment of employees and in the area of

acquiring knowledge from the external environment. The results of this analysis

are presented in Table 1, where the process of acquiring employees’

own knowledge is clearly visible through various management methods such as

compliance of competences with the position, employee activation strategy,

designated fields of activity, management decentralisation, motivation system,

open innovation, competency management, internal communication system,

controlling, implementation of quality systems, process management, integration

and open discussions, workshops, training system of company’s new joiners

and training materials, including published and non – published

materials.

The balance of loss and acquisition

of employees’ own knowledge presents a heterogeneous picture. During the

recruitment process, employees are sought for specific job positions where job

ranges are defined. In the case of management members, more knowledge is

obtained from the employee when competence complies with the position, while in

the case of employees, the balance sheet is negative (more employees’ own

knowledge remains unused). The new employer usually does not ask for knowledge,

but only checks if he has the knowledge he needs. In this way, the additional

knowledge acquired by the employee before is not subject to the transaction

related to current employment.

Fig. 4. Place of Competence

Management System in an enterprise management system Source: author

Fig. 5. Share of

knowledge in industrial processes

Source: author

The second area where the balance

of loss of employees’ own knowledge can be defined as unfavourable is the

type of knowledge that is derived from the external environment both by the

employee and by the employer. Previous management practices in the form of

integration meetings or open discussions do not ensure that a large part of the

company’s knowledge remains available to the employee. The company

acquires more knowledge by imposing an obligation to educate young employees,

and in developing areas through obtaining publications and unpublished works,

often in the form of manuals or handbooks.

Tab.1

Balance of loss and

acquisition of the employee’s knowledge.

|

The scope of knowledge |

Loss of knowledge% |

Acquiring knowledge% |

+/- % |

|

Knowledge brought by an employee |

Management members 30 Directors

30 Employees

50 |

Compliance of competences 70

20

10 Activation strategy 20 Activity areas 10 |

+40 -10 -40 }+20 |

|

Management system |

Management members 20 Directors

40 Employees

40 |

Decentralisation of management 20 Motivation system 40 Open innovation 20 Competence management 40 |

}+20 |

|

Information processing

system |

Management members 30 Directors

20 Employees

5 |

Internal communication

40 Controlling

30 Computerisation 25 |

}+20 |

|

Production system |

Managment members 40 Directors

20 Employees

10 |

Process management 50 Quality systems 40 Quality trainers 30 |

}+30 |

|

Knowledge from the external environment |

Training 40 Self-education 50 Acquired information 50 Experiences 30 Personal contacts 70 |

Integration meetings 20 Open discussions 30 Training of new employees 70 Unpublished works /

publications 50 |

}-70 |

Loss of employee’s knowledge

in the field of training is related to the company’s financial losses.

Such investment in an employee remains only as the company's costs. The

employee returns from the training and nobody expects anything from him, and

yet he could pass on the acquired knowledge to other employees or transform

this knowledge into innovative ideas.

The employee’s knowledge also

results from his personal contacts, self-education or information gathered

directly from the environment. In this case, the loss and acquisition balance

is negative as well. Research has shown that only a few employees, in a

well-managed company, could notice the use of the so-called “advance

knowledge” for the needs of the enterprise.

5. CONCLUSION

The challenge of modern industrial

management is to acquire intellectual resources and creative staff that

increase the value of the company in a non-investment manner. Because of the

growing link between industries and services in many aspects, unilateral

promotion of the service sector is not a suitable strategy to stimulate

collective growth and employment. The results of this research illustrate the fact

that these services, which show an above-average growth (services connected

with enterprises), directly depend on the production demand and the

employees’ competencies. Technological innovation consists of the

introduction of new production methods, new ways of implementing services and

the adoption of new organisational order in the domain of production processes

or services.

The mutual relations of industrial

enterprises and service providers also play a significant role. Between them,

there is not only the exchange of goods and services but also the transfer of

knowledge. It can be assumed that in sectors of the economy where there is

intensive cooperation between producers and service providers, a much greater

amount of new knowledge is generated than the other ones. However, we

encountered a significant amount of unused employees’ own knowledge that

is not shared with co-workers or employer everywhere. The greatest loss of

employees’ own knowledge concerns knowledge gained from the environment

in the form of training, self-education, acquiring information, gaining

experience and obtained through professional contacts.

Technology transferred through

training and transfer of know-how is measured by the costs of resources used to

carry them out. Payments for technology are provided in the form of royalties

(for example, for copyrights) and license fees with a systematic increase since

the eighties and intra-firm trade between parent enterprises and their foreign

subsidiaries showing constant development.

Enterprises use many solutions that

support knowledge management by participating in management operational

systems, such as employee competency management, employee activation

strategies, computerisation, quality systems and motivation systems. The innovation

rate defines the share in the surveyed population of industrial enterprises

that introduced technical innovations over a 3-year period.

However, research has shown that

the balance of loss and acquisition of employees’ own knowledge is still

negative, which means that current management practices are not sufficient,

there is no focus on the so-called “advance knowledge”, which is

located in the intellectual capital of employees. Only the management of

intellectual capital that creates the conditions for greater acquisition of

this type of knowledge.

References

1.

Ferenc R., O. Kunert. 2011. Innovative strategy construction for a

capital goods producer. Monographs of the Lodz University of Technology.

2.

Ferenc R., O. Kunert. 2013. MeRKI-U: a method for research and

development in the industry. Foundation for Competence Promotion Lodz.

3.

Grudzewski W.M., I.K.

Hejduk, A. Sankowska, M. Wańtuchowicz. 2007. Managing trust in virtual organizations. Warsaw: Difin.

4.

Jacyna-Gołda I., M. Kłodawski, K. Lewczuk, M. Łajszczak,

T. Chojnacki, T. Siedlecka-Wójcikowska. 2019. “Elements of perfect

order rate research in logistics chains”. Archives of Transport 49(1): 25-35. ISSN 0866-9546.

5.

Kisielnicki J. 2016. Virtual means Intelligent. In: Management of the 21st Century, Infor

special editions.

6.

Kunert O. 2011. Competencies of the polish manager. In: Competencies as a constituent of the success

of a modern company. Published by Foundation for Competence Promotion Lodz.

P. 17-25.

7.

Kunert O. 2016. “The role of logistics in creating company

value”. ZN WSOSP 2(29): 39-53.

8.

Musenga F. Mpwanya, Cornelius H. (Neels) van Heerden. 2015.

“Perceptions of managers regarding supply chain cost reduction in the

South African mobile phone industry”. Journal

of Transport and Supply Chain Management 9(a176): 1-11. ISSN: 2310-8789.

9.

Penc J. 2007. Innovative

Management Controlling Changes in the European Integration Process. Lodz:

WSSM.

10.

Serenko A., N. Bontis. 2004. “Meta-Review of Knowledge Management

and Intellectual Capital Literature: Citation Impact and Research Productivity

Ranking”. Knowledge and Process

Management 11(3): 185-198.

11.

Stachowicz J. 2007. “Social Networks in the Processes of

Social/Entrepreneurial Capital Building as the Determinant of Development of

Contemporary Regions”. Paper

presented during the Clusters & Regional Development Workshop, IDEGA-USC.

Santiago de Compostella, Spain.

Received 29.09.2019; accepted in revised form 28.11.2019

![]()

Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License