Article

citation information:

Rutkowski, M. Civic transport duty as

service performed for the tsarist army stationed in the Kingdom of Poland in

the light of the Transportation Act of May 4, 1858. Scientific Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series

Transport. 2019, 103, 119-142.

ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2019.103.10.

Marek RUTKOWSKI[1]

CIVIC

TRANSPORT DUTY AS SERVICE PERFORMED FOR THE TSARIST ARMY STATIONED IN THE

KINGDOM OF POLAND IN THE LIGHT OF THE TRANSPORTATION ACT OF MAY 4, 1858

Summary. This text focused on the

implementation of the provisions concerning civil transport services rendered

for the sake of the Russian occupational (Active) Army stationed in the Kingdom

of Poland by the Administrative Council of the Kingdom of Poland, there. The

above-mentioned Transportation Act of May 4, 1858, generally refers though to

the old solutions, mostly in force since 1831, or even from the time of the

pre-revolutionary era. Writing down and introducing once again some of these

provisions was, as it might seem, a part of the process of regulating within

the frames of law, this aspect of relations between the invading Russian

military power and the Polish subdued society.

Keywords: civic transport duty,

tsarist army, Kingdom of Poland, 19th century

1. IMPLEMENTATION OF THE

TRANSPORT DUTY AT THE BEGINNING OF OPERATION IN THE CONQUERED KINGDOM OF POLAND

BY THE OCCUPYING RUSSIAN (ACTIVE) ARMY AFTER SEPTEMBER OF 1831

The issue of transporting

people and goods belonging to the operating tsarist military units,

particularly the (Active) Army in the Kingdom of Poland, in the inter-uprising

period of 1831 - 1862 was an extremely complicated phenomenon that was burdened

with a number of legal conditions, especially significant after the beginning

of the overt occupation of the country in September of 1831. Already on October

6, 1831 (actually the day after the final crossing of the Polish borders to

Prussia by 20,000-strong General Rybiński’s Corps, consisting of the

main remaining Polish troops), the Russian-dependent Warsaw’s Government

Commission of Internal Affairs and Police issued a rescript No. 9598, in which

the ministry applied to the Provisional Government of the Kingdom for the

introduction and establishment of some (new) provisions, concerning

“civic transport duty to be undertaken by citizens for the sake of the

Russian army”.

In the meantime, its two

members, General Rautenstrauch and General Kossecki notified the Provisional

Government about the initial decision of the Russians (Active) Army, the

highest authorities in this regard. Interestingly, these two Polish soldiers,

as “participating in conferences with the Chief of Staff of the

Army”, announced that the Muscovite side decided to maintain in the

Kingdom of Poland, the provisions concerning military logistics, that was

issued on May 24, 1823, on the order of the Russian Grand Duke Constantine who

constantly resided in Warsaw at that time.

Consequently, the Provisional

Government was ordered during its seventh session of November 11, 1831, to

provide the Government Commission of Internal Affairs and Police with

information that it was absolutely necessary to fully comply with these

solutions, stating that any further divagations about the establishment of new

laws referring to transport services delivery for the Russian Army should be

considered pointless[2].

The above conduct of affairs,

of course, did not prevent any further release of the series of orders and

regulations to the army (especially issued by Russian Field Marshal Ivan

Paskievich), which clarified and modified the original logistic military laws.

The first of such modifications took place on November 12, 1831, when the new

tsar’s governor, Paskievich issued his earliest order to the (Active)

Army in this regard, by No. 561, which however, officially called for

compliance with the regulations of 1823[3].

Generally, the commencement of the process of the formal

use of delivery by the civilian army transportation carts and wagons was

available in the period after the fall of the November Uprising, in the

military staging areas, established on the main routes of the Kingdom. The

tsarist army used, as a rule, the whole fleet of private cart vehicles in full

accordance with the “open road transport lists”. The relevant

demand was immediately transferred to the municipalities, and means of

transportation were delivered “with intermediation” of the civil

authority.

This formal duty was at the beginning of the Paskevich

period, carried out by municipalities which in accordance with a predetermined

order were needed and after obtaining orders directly from the concerned

military authority, provided well organised carts and wagons “in

nature” to the staging areas, established as it was mentioned above,

close to the most vital roads of the Kingdom. As before the Uprising of 1831,

the fee for civic transportation was determined by the order of the Russian

Field Marshal Ivan Paskievich in the amount of 1 Polish zloty and 15 groshes

(that is, one and a half of zloty) for a verst/mile, paid for a

two-horse-drawn cart or wagon. Funds for

this purpose were originally transferred by the Army's Commissariat, but the

original source of this money came from the Polish State Treasury, that is,

from collecting local taxes[4].

Since 1834

(about three years after the final defeat of the Polish army), there

continuously appeared numerous marches and assemblies of Russian troops in the

Kingdom of Poland, prompting a

strong need for accurate and constant supervision by the civil authorities,

performing civic transportation obligations. Hence, in its report of 1834, the

Governmental Committee of Internal, Spiritual and Public Enlightenment Affairs

stated with satisfaction (after due inspection) that “throughout the

country” the carts and wagons for the army were delivered regularly, and

“with high accuracy”[5].

Also in 1835, the performance of a large-scale process of

fulfilling the transportation requirements was provided in response to an even

larger demand for the tsarist army, which was then almost constantly on the

march. Most importantly, from the point of view of the occupying power, at that

time, no irregularities were found in the “attitude” of the

residents of the Kingdom towards complementing these duties[6]. This was in spite of the fact that during this year,

the famous Russian-Prussian military parade and drills took place near the then

Russo-Prussian border city of Kalisz[7], where it was necessary to provide significantly huge quantities

of military transports.

Existing in the second half of the thirties of the 19th

century (for example, in 1838) during the diverse marches and dislocations of

military units and commands in Poland, “there were submitted by many

local citizens, private transportation vehicles, [being] at the disposal of the

competent [military] authorities". Despite being the obvious military

source of demand, the burden of civic transport service for the army was

constantly exercised only on the basis of response to exact orders submitted by

the government to the local administrative staff[8].

The implementation of these formal transportation

obligations was at 1838, associated mainly with the dislocation of the 4th

Infantry Corps of the Russian Army in the territory of the Kingdom of Poland.

This particular corps held various marches during the twelve months of the

year, “either making a replacement to the military garrison stationed in

Warsaw or assembling for the camp” near the Polish capital. It was only

from this camp that individual parts of the 4th Infantry Corps were subjected

to further dislocation to chosen places of permanent abode in the Kingdom.

Another reason for the extraordinary frequent marches of the tsarist army

stationed in the Vienna Congress,

Poland, in 1838 is tied to the imposition on the mentioned 4th Corps of the

(Active) Army’s duty to convoy fresh recruits, being led from the Vienna

Congress, Poland, to the main territory of Nicholas I’s Empire[9].

Finally, it should be noticed here, that apparently in

the period following, particularly in the span of the forties and fifties of

the19th century, until 1858, there appeared a considerate number of changes in

the formal frames of the performance of civic transport services done to the

Russian Army (which was partly inspired by disturbances in the European policy,

especially after 1848). However, it can be said that besides the necessity of

fulfilling the huge requirement of the Russian (Active) Army, almost constantly

being on the move in Poland with diverse exercises and drills, the obligation

of transporting recruits seems to be one of the main transportation burdens in

the entire inter-uprising interval that was carried out in conquered Poland for

the needs of the Russian occupation military staff.

2. TRANSPORT ACT CONCERNING CIVILIAN SERVICES

FOR THE RUSSIAN ARMY STATIONED IN THE KINGDOM OF POLAND, FROM MAY 4, 1858

After the changes caused by Russia's defeat at the

Crimean War, among many “facilitations” introduced with the consent

in accordance with the intentions of the new Muscovite tsar - Alexander II, the

development of detailed regulations regarding the implementation of

transportation duty carried out in the Kingdom of Poland (in particular:

providing private transport for the Russian army stationed in the occupied

Vienna Congress Kingdom) found its turn. The aim was to introduce into the

Kingdom such duty of the transport service on which lies its (new) solutions in

legal forms, authorising the supply of carts and wagons for the army on principles

similar to those applicable in the Russian Empire itself. The idea was as

though these solutions would have “possibly been reconciled with the

[geographic] location of the country, with local customs and local

relations“. As it was primarily said, the main task of the lawmakers was

now to clarify the weight of the load, which should be carried by the private

carts and wagons for delivery to the army[10]. It seems it was a difficult task, whereas in the

Russian Empire mostly and basically only one-horse carts were used, with the

permissible load weight of up to 15 pounds (that is, 246 kg). In the Kingdom at

the same, time there were one, two, three and even four-horse wagons in

permanent usage, which of course implied an increased in the weight of the burden

they should carry[11].

The

Government Commission finally elaborated the relevant regulations for Internal

and Spiritual Affairs, which remained at that time under the authority of the

Chief Executive President of a pure Russian nationality, Secretary-Counselor

Muchanov. During the development of a new draft of the law, the Chief of Staff

stationed in the Kingdom of Poland’s First (Active) Army submitted

numerous applications.

In

the final version of the new draft of the law, the forms of “recalculation”

methods and rules of transporting goods and items by the Russian army,

stationed in the Empire itself as in the Kingdom of Poland, were specified.

Precisely, the 16. Article of the new law act in its appendix No. 2 deliberated

this issue in details, indicating that two-horse vehicles operating in the

Kingdom should take cargo intended for four-horse units operating in the

Russian Empire (even these ones were rarely used in Russia). At the same time,

three one-horse wagons from the Kingdom were considered to be equivalent to two

one-horse carts from the Imperial territory. Due to these theoretical

calculations, a rather complicated logistic problem was solved (but that

happened only as late as in 1858, 27 years after the fall of the November

Uprising). From then on, it became legally regulated that a Russian military

unit arriving in the Kingdom of Poland from the Russian Empire, for example,

with the burden taken there on four one-horse wagons, had the right to demand,

while entering the territory of Kingdom, the “substitution” (which

means delivery of civic transport means), composed of three two-horse carts or

six one-horse wagons, etc.[12].

In

the pre-final stage of the legislative process, the new law was outlined,

arranged and prepared by the Government Commission of Internal and Spiritual

Affairs and the Chief of the General Staff of (Active) Army. Having discussed

all the details among themselves, the lawgivers formally presented the new law

for acceptance to the forum of the most important civic administrative

authority of the Kingdom, the Administrative Council. Discussion on the subject

(according to the minutes) took place on April 22 / May 4, 1858, when following

the general line of the supposition of the military representatives of Tsar

Alexander II, the same day, the Administrative Board decided to fully confirm

the new civic-military transport provisions.

The

new law was officially entitled: “The provisions on the supply for the

army of carts of citizens in the Kingdom of Poland”. Secondly, it was

clearly stated on May 4, 1858, that the new law, as formally binding on both

military and civilian, would become the regulations in force, starting from

June 19 / July 1, 1858. Point three of the regulation mentioned that all

provisions introduced in the past in the field, concerning the supply of

private vehicles for the Russian troops stationed in the Kingdom of Poland have

lost validity; this was supposed to happen exactly on the date of effect of the

new legal solutions. Finally, the Administrative Council ordered the posting of

the new regulation in the Official Law Digest of the Kingdom, for which the

Government Commission of Internal and Spiritual Affairs was responsible.

In accordance with the general

criteria used as the basis for military transport regulations in the Kingdom of

Poland, its application in relation to the civilian population was based on the

general principle of carts and wagons being delivered by residents of both

cities and municipalities. However, in the Capital City of Warsaw, contracts

for military transport services was signed with accepted entrepreneurs (who

would act as a sort of substitute for the inhabitants) who undertook the

implementation of this task by concluding an appropriate contract with the

city’s magistrate. Such agreements had to be approved by the Government

Commission for Internal and Spiritual Affairs. Another important principle

worth mentioning here was the recognition of the obligation, which considers

the transportation service duty as binding in the field of movement of military

people as well as goods/items, generally belonging to the tsarist army.

Article 2 of the Act of May 4,

1858, stated that the carts and wagons had to be supplied by the public

“for transporting from one place to another, military loads and

requisites. This is possibly due to the implementation of the military personal

movement process, as well as due to the movement of any other persons

possessing, under the provisions of the Law on Transportation, the right to

demand delivery of [private] transport to them”. With a clear assumption

of providing mostly two-horse carts and wagons for the transporting of

items/persons, the legislators pointed out the awareness that in some

territorial regions (parts) of the Kingdom, it was a common and vivid rule to

use only single-horse vehicles for carrying loads, which in turn meant the use

of only such harnesses in those areas, that were adapted to be used by one

horse only.

In connection with the above,

Article 3 of the new law act allowed the use of one-horse wagons to carry goods

belonging to the Russian army, stationed in the Kingdom. The principle of

“counting” two one-horse carts for the replacement of one two-horse

wagon was applied here, this refers to both the calculation of the size and weight

of the transported load, and to the calculation of fees for using such

transportation vehicles. On the other hand, in the case of transporting

military and other persons entitled to use this private service, it was

possible to deliver one-horse or two-horse carts or wagons, this depended on:

a) “requirement”; b) circumstances; c) and local customs. Such a

solution (that is, allowing the use of only a one or two-horse vehicle instead

of other means of transportation) was not in force in a number of special

incidents or occasions, involving staff-officers and ober-officers. It was also

not allowed to make such a replacement in a considerable number of situations

related to the implementation of the military census, or the transport of

recruits. Finally, in the content of “general entries or

situations”, there was also a reservation about the possibility of

extraordinary demand of: a) three-horse vehicles; b) four-horse carts and

wagons; c) transport carried out by oxen; d) and only horses themselves[13].

The

second chapter of the Civil-Military Transportation Act specified the type of

military units and sort of persons that possessed the privilege to take

advantage of the use of the obligatory delivered vehicles in the Kingdom of

Poland. Foremost among these, are included such privileges: a) regiments and

battalions of sappers and customs riflemen; b) batteries and parks of tsar's

artillery; and finally and most spoken about c) “other army units”.

According to Article 6 of the Act of May 4, 1858, it was necessary to deliver

and provide all of these (being in March) units, fully satisfactory and

abundant number of horses and vehicles. This had to be provided in exactly the

same quantity as it was displayed in the individual orders issued to the

(Active) Army, as well as in the other authorisations issued by the military

commander-in-chief, mostly in the form of road cards.

In

addition, authorised officers with the responsiblity of drawing of plans and

making similar reconnaissances, or any scientific activities (like scientific

research for instance) of a strictly military nature were also granted the use

of these deliveries by the civilian populace vehicles. This concerns “all

military delegates [sent] in the service's interests”. The condition, however,

to obtain the possibility of using the carts and wagons was in all these cases

dependent not only on the issuing of the road cards to all previously described

individuals in accordance with the applicable regulations, but also on strict

accessibility to the special fund, allocated to cover the renting of a vehicle

for them. Such content of Article 7 of the Act of May 1858 was based on the

instruction of the order issued previously by Marshal Paskievich to the

(Active) Army on October 31 / November 12, 1831, no. 561, and especially in

Articles 2 and 3. On the other hand, staff-officers sent for business purposes

(except for situations referring to the work of conscripts commissions and for

running recruits), received four-horse carts and wagons at their disposal. Additionally,

each of the ober-officers and all members of the staff holding equivalent

positions in the Military Board received the right to use two-horse wagons. In

the event, that several ober-officers journeyed to the same location, then one

two-horse vehicle was allocated to two of them each, regardless of whether they

are accompanied by servants or not[14].

The transport of military

patients is extremely important from the point of view of the idea of proper

solving of logistic problems, therefore, was planned in a very precise way. In

this relation, it was then described in detail in the new provisions, first,

the appropriate procedures for travelling through the territory of the Kingdom

of Poland of: a) military units at the moment of passing the Russian-Polish

border, not encountered among the current full time composition of the Active

Army military powers stationed there, and without their own medical

“props”; b) individual army “commands”, marching

through successive stages.

In these two cases, the new

law precisely indicated the number and size of carts and wagons to be delivered

for the purpose of transporting military patients, calculated in relation to

the numerical status of entire units. Consequently: a) for single-unit commands

composed of up to 25 soldiers, one single-horse cart was to be provided; b) for

commands with a personal composition closing between 25 and 50 people, one

two-horse vehicle was reserved for the transport of patients. In this way, the

principle of enlarging the “sanitary transportation fleet” of a

given marching/riding horse military unit in relation to a one-horse wagon for

every (next) 25 people, or a two-horse vehicle for each of the next 50

soldiers, was adopted.

The principle of the maximum

limitation on the use of means of transportation for the sick “ordinary

soldier” patients was introduced. As a result, in the unit composition of

up to 50 people, with no more than one or two ordinary soldiers (privates in

particular) in sick condition, then it was ordered to add to such a

marching/riding column only with one single-horse wagon “for use”.

For three or four patients, it was necessary to secure one two-horse cart in

such a department, while for five and six non-disposable military persons, the

legislation provided a single-horse cart and a two-horse wagon for their

transportation; successively, for seven and eight patients it was necessary to

provide a double two-horse wagons, etc. As a result, the principle practice of

having the carriage of one or two patients on a one-horse cart as well as three

or four patients on a cart drawn by two horses was developed.

Furthermore,

non-standard incidents were not forgotten, that is, concerning transporting

military patients through those areas of the Kingdom of Poland where the practice

of using “only two-horse carts” was overwhelmingly practised.

Hence, in areas of the country where such common practice was in general

acceptance, instead of carts drawn by one horse, it was formally possible to

add the sanitary services of the tsar's army for just two-horse wagons, thus

replacing the original arrangement and purpose of the single-horse vehicles.

However, when in effect it turned out that in accordance with the provisions of

the Military Transport Act, it was possible to deliver only carts with two

horses, then the payment made by the authorities for providing transport

equated the regular sum paid for providing the one horse-drawn vehicle.

Alternatingly,

in these areas of the Kingdom, where only one-horse wagons were traditionally

used, they could be supplied for the medical purposes of the Russian army

instead of two-horse vehicles. It was clear that two wagons with one horse were

formally "the equivalent of a two-horse transportation vehicle”. All

these solutions, posted in the content of Article 9 of the Act of May 1858,

seemed to bear direct reference to the provisions already contained in the

Order No. 196, addressed to the (Active) Army on October 12/24, 1837, as well

as in Articles 1732, 1733 and 1734, published in the Book III, Part IV of the Military Declaration Digest of 1838[15].

A separate and extremely

important issue was the matter of transporting officials in active

participation in the military census taking place successively in the Kingdom

of Poland, as well as in the process of recruitment of Polish citizens to the

tsarist army. To secure their proper transport, all members of the Census

Delegations and Recruiters' Offices (Recruitment Offices), as well as the

clerks/writers assisting them, had to be provided with carts and wagons

delivered by the local inhabitants of the country. Similar rights were also

assigned to officers of the Russian (Active) Army affiliated to the Census

Delegations and Recruitment Offices, who were themselves obliged to travel

“to the appropriate places to settle recruitment activities”. Similarly, the same privilege was

granted to the officers of the (Active) Army that were instructed to perform a

military census, and as such “translocated” from one area to

another.

While performing these duties,

the following classes of military staff and clerks or officials were supported

in the form of delivery of diverse types of transport motion as: a) for

staff-officers - three-horse wagons; b) for ober-officers - two-horse wagons;

c) for civil servants of the sixth administrative rank - four-horse wagons; d)

for civil servants of the seventh and eighth administrative ranks - three-horse

wagons; e) civil servants of the ninth and tenth classes - two-horse wagons; f)

for officials of lower classes of administrative classification, sent alone to

perform their duties - two-horse wagons; g) and finally, for officers and

administrative aides sent in groups

(usually in a number of two individuals) -a two-horse wagon. Such a solution, contained in Article

12 of the analysed Civil-Military Transportation Act, corresponded to the

previous entries written in: a) the tsarist order (ukaz) of 1850, referring to

diets and travel costs, b) in the Instruction for the Chiefs of the Recruiters

Units of October 21 / November 2, 1853; c) and in particular in Article 20

thereof Regulation[16].

The

law of May 4, 1858, in its Article 11 confirmed that sick “military

census members” (persons selected in obligatory recruitment to join the

ranks of the tsarist army) are to be transported from individual district

(poviat) towns of their origin to the actual places of enrolment of already

chosen recruits with the support of civic transportation measures. In these

cases, they had to be transported (but only in case of being ill) on a one or two-horse

carts and wagons, whose obligation had to be performed on principles identical

to those described in – aforementioned Article 9 of the new provisions.

In addition, it was necessary to provide transport for one or two officials,

running and directing the unit/group of the newly recruited military census

members. These officials, possessing specific allowances, were apparently

obliged to pay instantly from their subsidies for the fare of vehicles they

took. Such solutions were a sort of direct reference to the decision of the

Administrative Council of March 23 / April 4, 1837, No. 3061[17].

According

to the new law, during the transport of recruits from the Kingdom of Poland to

the territory under the direct power of the Russian Empire, different vehicles

had to be delivered for different eligible categories of men. Therefore, for

the chiefs of successive recruit units/parties, the following were assigned: a)

those in the rank of non-commissioned officers – the-horse wagons; b) the

ober-officers - two-horse wagons. In the case of chiefs, the private transport

on carts or wagons was provided for them either to the final assembly point or

to the Kingdom’s border and back.

Also

for the physicians accompanying the recruitment units, different numbers of

transport horses were allocated, according to their military of civil

“ranks and grades”. So one can see that: a) the staff physicians,

in the rank of staff-officers, received the three-horse wagons; b) doctors with

lower administrative grades than a collegiate assessor were guaranteed to use

carts with two horses. Essentially, as in the case of the chiefs of the recruit

parties/units, transport privileges included physicians or doctors travelling

to the point, where some other authorities would take supervision over these

recruits, which traditionally happens at the border of the Kingdom, and

returning to the place of their permanent abode. Another category of people who

had the right of use of civic transport for the sake of their movement in

connection with the “delivery of new recruits” were the

non-commissioned officers, sent in front of the marching column to prepare the

suitable quarters in advance. They possessed the privilege to use a two-horse

cart for these purposes, but carrying them no further than the assembly point,

or to the exact border of the Kingdom.

The

general transport for sick recruits was organised on similar terms as those

described in Article 9 of this Act. Finally, in the case of transporting

soldiers weakened by sickness, being enrolled in the commands escorting

recruits, the same legal conditions were applied, granting them civil transport

to the assembly point, or to the Kingdom’s border, and on the way back to

the permanent residence of their regiment. This solution was adopted in 1858 following

Article 20 and 156 of the Instruction for the Chiefs of the Recruiters Units from October 21 / November 2, 1853[18].

Civil vehicles were also

supplied on similar terms as those specified in Article 9 of this Act for

several other categories of people. They mainly include: a) soldiers

experiencing disabilities, b) other seriously ill lower-rank military, who were

just released from the army and were “handed over” to the civil

authorities. Besides military cripples and seriously ill soldiers, a strongly

confirmed possibility to use a civic transport was also granted to the wives of

a deceased military (alone or with children), who were travelling to places of

their original settlement, or residence. Such support could be granted

“through the mediation of civil authorities”. The same privileges

included the “constantly vacant soldiers” who could not continue on

their way to their chosen place of permanent residence by marching on their own

feet, mostly on the grounds of weakness.

All these categories of people

were assigned transport, though, only at the beginning of the process of

transferring them from the “state of form of military readiness and

obedience” under the supervision and care of the civil administrative

power, they were simultaneously given and provided with “formal calls for

civic transportation”, signed by the local (gubernia) war chiefs or by

the (military) city commanders, and eventually by the governors of the military

staging areas. Another possibility was the firm recognition by the civilian

branch of the Kingdom’s administration, under which the given former

military people were shifted the indispensable need to provide them with some

transportation means. These solutions were adopted in 1854, respecting the

decision of the Administrative Council from December 18/30, 1842, No. 31 595[19].

It sometimes happens, that

wives and children of recruits or soldiers of the tsarist army coming from the

territory of the Kingdom of Poland, might be willing to follow their

“husbands and fathers being relocated from the Kingdom to the

Empire”. In such a case, Article 14 of the Act of May 4, 1856, granted

them the free delivery of a cart or wagon at each staging area. Such

entitlement meant granting: a) a single one-horse cart for one, two or three

wives of soldiers or recruits; b) an identical form of transport for three

travelling children of soldiers, or recruits. This solution resulted from the

provisions of the order (ukaz) of Field Marshal Paskievich, addressed to the

(Active) Army of March 24 / April 5, 1835, No. 465, and the decision of the

Administrative Council of March 31 / April 12, 1842, No. 24 050[20].

Besides the

army staff itself, members of some other quasi-military services were also

entitled to use civic transportation. Following this idea, the gendarmes

(members of the transport police) would escort to the provincial cities,

people: a) accused of arbitrary/illegal crossing of the border and b) hand over

to the Russians at special exchange border points by the other two partitioning

countries (Prussia and Austria). Similarly, civic carts and wagons were used to

transport in military convoy “criminals, charged with political

activities”. For this type of escorting, not only the gendarme were

employed, but also the Don and the Ukrainian Cossacks, or military cripples,

still in charge. The return journey of these gendarmes, Cossacks, etc, was also

secured by providing them with civic one-horse vehicles.

The

regulations from May 1858 defined the exact permissible weight of the items

carried for the army on the civic carts and wagons. Primarily, it was noticed

that during the passage of the military from one place to another, the number

of vehicles intended for transporting “ammunition” (the last

wording was the exact phrase used in the Russian version of the text, while in

Polish, the phrase of unsuitable or rather unknown today phrase

”cejchhauz” was invoked) should be adjusted to the weight of these

items transported. In order to meet these requirements, it was assumed that a

single two-horse wagon should be laden with a load not exceeding 20 pounds

(327.6 kg). Nonetheless, in those parts of the Kingdom, where it was customary

to use vehicles drawn only in one horse, each cart could be filled with load

not exceeding the amount of 10 pounds (164 kg) [21].

In addition, it was also assumed that in the case when the weight of cargo to

be transported varies between 164 kg and 328 kg, it was necessary to provide a

single two-horse wagon for its relocation. On the other hand, where a load with

weight varying between 328 kg (20 pounds) and 492 kg (30 pounds) was to be

transported, it was required to provide a two-horse platform and single

one-horse wagon in order to properly transport this product.

Having

calculated and indicated the permissible limit ranges of loads carried on

individual private carts and wagons, it was explicitly expressed that among the

various materials and objects transported by the military, civilian vehicles

should carry only those items, which the authorities include in the category of

goods whose transport in civic service was guaranteed by the existing

legislation. Hence, before leaving from their permanent locations, it was

customary for the “departing regiments” of the (Active) Army, to

undergo the whole procedure of weighing these items or goods. It was, however,

permissible to leave this sort of activity to the least partial responsibility

of the representatives of the local civil authority.

After

such a weigh-in, representatives of the civil administration of the Kingdom

would issue a written certificate for the regiment or other military units,

containing information on the “weight of the load of items

carried”. Subsequently, the commander of the regiment or unit should have

presented to his superiors a certificate of weight of the transported goods,

that he had previously received from the civil administration representatives.

The next step in the procedure was to supply him with a “road

card”, based on which the local regiment of the army commander could

request the delivery of the suitable number of citizen's vehicles.

Article 19 of the law of May

4, 1858, described conditions (according to the author of this text, -

mentioned here, most probably meant the relative frequency of trespassing the

existing provisions, including at least that merit) for transporting materials

necessary to sew military uniforms, as well as “ammunition items”.

Apparently, it was a general rule here that one could demand vehicles suitable

“for carrying various [State] Treasury effects referring to uniforms of

soldiers” and “ammunition stuff” (it is worth mentioning that

this last type of commodity does not appear in same passage of the Polish text)

to the place of steady or permanent accommodation of the military unit. But in

order for civic vehicles to be granted such privileges, there were some strict

conditions attached and it was possible only when: a) the regiment, eventually

some other unit of the tsarist army, having received materials from the

Commissariat of the Army, was for one reason or another unable to complete the

delivery of full dress uniforms for soldiers; b) problems occurred while

completing some activities related to the preparation of these

“ammunition materials” on the spot. In both cases, the

“external delivery” supported by civic means of transportation

might have taken place not later than three months from the date of the

problem. Nonetheless, it was strongly pointed out that in the event that after

the said three-month period from the date of their receipt from the Army

Commissariat, these goods were still unprocessed, then their further transport

should not be carried out on civilian grounds, but rather be carried out at the

expense of the individual military commanders responsible. In these circumstances,

it is suitable to admit that in a case when any possible delay in the preparation

of soldiers' uniforms or required “ammunition materials” was caused

by events “deserving justification”, then the appropriate military

authorities should call on their immediate superiors in order to obtain

authorisation request for the delivery of civic transportation of these goods.

Such a solution was in line with order No. 15, issued by the (Active) Army

commander-in-chief in 1856. The load of the “sewing” and

“ammunition” materials to be transported was, moreover, set in

exactly the same way as for all other military “utensils”[22].

In reference to the problem of

the road cards, legislators decided

in May 1858 to express the strict rule demanding that the civic vehicles be

formally made available exclusively only to the members of the Russian army who

would be able to provide such a “referral for use of a civic

transport”. Despite these clearly spoken conditions, the solution at

stake was not to be performed arbitrarily and at all time. Firstly, the

commanders of the gendarmerie had the right to request for private

transportation delivery without presenting any road cards, which, however, did

not release them from the need to pay the appropriate monetary rate for the

trip. The local civil authorities were obliged to issue receipts for

transportation fees obtained in this manner. The above was based on the

decision of Ivan Paskevich, acting as a tsarist governor of the Kingdom of

Poland, which was published on June 24 / July 6, 1843, under No. 3 208[23].

Likewise, officers and members

of other military staff involved in carrying out conscripts, and transporting

recruits did not have to show their road cards. As it was stated in point b) of

Article 20 of the law act discussed here, the lack of the need to show road

cars (this time it was written in the original: “destination card”) resulted

this time from the possibility of presenting by them, some other

“ordinances of the appropriate authority”, that would be shown for

inspection instead of a road card.

One way or another, there was

the substantial need to write in such an ordinance, the information concerning

the exact authority claim for the delivery of the private vehicles, required

for the execution of the military-administrative process of relocation of items

and people[24].

Of

course, road cards were made according to a uniform official sample. These

cards, signed by the Main Army Commissariat were officially issued “on

the orders of the Serene Lord, Tsar of All Russia, King of Poland, etc”.

Formally, the person responsible for issuing the road cards was apparently the

current duty officer (in the rank of a general) of a tsarist army. If the

general on duty either did not want to or could not sign all the road cards

personally (which was rather reasonable to expect as doing so consumes much of

his time), he could just simply send blank forms of these cards to individual

staffs of corps and divisions, deployed in the Kingdom of Poland, as well as to

the commanders of fortresses and cities, and finally to the governors of

provincial governorates (interestingly enough, in this census the

“military district/poviat army chiefs” were omitted). Whereupon

this last solution was introduced, then was the issuing of the military road

cards “ continued as the need arose and in strict compliance with the

regulations”. It was a direct reference to the already mentioned command

of Field Marshal Paskievich to the (Active) Army of October 31 / November 12,

1831, No. 561 made in full compliance and accuracy to its Article 10. The

chiefs of diverse departments of particular types of troops in various military

boards, receiving these blank forms of the road cards were automatically

obliged to submit to the Main Army Commissariat a full summary of the current

use of these blanks. This solution would then be adopted in reference to the

order issued to the (Active) Army on June 16/28 1856, in its Article 13.

In

the content of the typical/standard road card, it was possible to read that it

was issued to the bearer by the proper authorities, valid from a particular

point of departure to the specific town / geographical point of arrival. It was

further affirmed that the card was issued “in accordance with the

regulations approved by the Commander-in-Chief [of the Active Army]”. All

of this resulted to the obvious conclusion that “it was recommended to

deliver [to the bearer of a given road card] at each staging area, marked in

the attached route scheme, a certain number of vehicles. It was not allowed to

deviate from the course of its designated route. The

road card stipulated at the same time the kind of civil transportation vehicles

to be delivered (usually these were one or two-horse carts and wagons, as only

these types of vehicles were originally mentioned in the standard form of the typical

card), and the fee for which each of these means of transportation were charged

for[25].

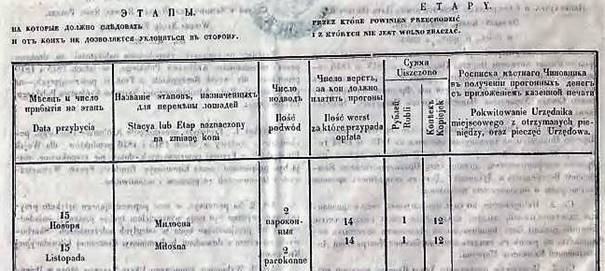

Fig. 1. Part of road card, describing the staging areas of the journey, according to

the Act of May 4, 1858[26]

Having

received a road card, as well as the exact sum of money required to cover the

anticipated payment for the hiring of the citizens’ vehicles, and finally

after completing part of the journey, a member of the military staff had to

make sure that the civil servant's receipt for collecting the money provided at

each staging area was exactly suitable for the number of versts/miles travelled

(and the number of carts or wagons delivered, with the number of horses used to

drive them). And above all, while in possession of the road card, the Russian

military had to check whether the amount of money accepted was in line with the

sum recorded in the appropriate “heading” of such a road card.

Another

duty of a given “beneficiary of civic transport” to the military

was the need to “showing back” a road card to “the same

authority that had previously signed it for him”, which had to be done no

later than two weeks after arriving at his final destination. In the event of

failure to meet these requirements by the person to whom the road card had been

issued, a complete sum of the money previously paid for renting a vehicle was

to be deducted from the salary of such a negligent military. Another threat was

to draw such a military man to “strict responsibility” for failing

to comply with the current legal regulations[27].

Generally, Article 24 of the

Act of May 4, 1858, recalled the conditions to be met so that road cards issued

for the purpose of transporting military people/items would correspond to all

formal requirements. The following conditions are shown below: a) the need to

enter the name of the regiment, battalion or unit in the proper

“heading” of the road card; b) the necessity of writing down the

name of the person for whom the card was signed; c) the need to write down the

exact person who would eventually use the card; d) to determine the departure

and arrival locations of the interested person. If the road card has been

issued for the whole military unit, then it was necessary to specify the exact

number of civic vehicles to be used: a) for carrying weapons and ammunition

etc; b) for sick soldiers; c) in relation to all other persons and items

intended for transportation from one place to another. Furthermore, there is

the need to enter in the road card: a) the number of versts/miles to be

travelled; b) the exact route of the journey; c) individual staging stations;

d) the total amount of currency to be paid for all civic vehicles used.

As it also resulted from, the

next Article 25 of the Military and Transport Act of May 1858, any civil

servants providing for the army, on the basis of presenting to him a road card,

civic transport vehicles (regardless of whether it was: the commune head,

president or mayor of the city, or any other official) - was strongly obliged

to "clearly" enter in the appropriate heading of this card, the exact

amount of money received for this service done. That official had to provide

the relevant information confirmed by his signature and application of the seal

to the exact page of the road card[28].

Additionally, it specified how

the chiefs of specific tsarist army divisions deployed in the territory of the

Kingdom of Poland must behave in the matter of issuing road cards for the

transporting of items and people by civic carts and wagons. This time

concerning these heads of army units and regiments, that were not consisting

the official parts of the military corps of (Active) Army. Indeed, it was

pointed out that, after having received from being under their command,

specific regiments, battalions and companies certificates of their readiness

for departure, confirming altogether the actual weight of the transported

“military effects”, these chiefs would issue road cards, permitting

hiring of private vehicles “ in the number corresponding to the overall

weight of carried goods”. This wording was explicitly applied to Article

12 of the command of Field Marshal Paskievich given to the (Active) Army on

October 31 / November 12, 1831, No. 561[29].

And finally, it seems

extremely important that there was included in the new law, the exact order for

the military authorities issuing the road cards to proceed with utmost accurate

compliance with the existing rules. None of the transport law was to be

violated by these formal activities. In relation to petitions that would not

meet these criteria, it was absolutely necessary to refuse to issue road cards[30].

Analysing the technical aspect

of payroll conditions for the supply of civic vehicles for the purpose of army

movement, the Act of May 4, 1858 stated in its Article 27, that the vehicles

delivered for the transport of military materials should be of capacity, where:

a) two-horse cart or wagon could carry the load of 20 pounds (almost 328 kg);

b) single-horse carts or wagons could transport the load of 10 pounds (about

164 kg). On the other hand, four-horse vehicles should be capable of taking up

to 40 pounds (656 kg) of the weight of various military goods, while a fee

equivalent to two fares for two-horse carts or wagons was paid for them. It was

a generally accepted rule that one could get only ½ of the number of

four-horse vehicles “in relation to the number of two-horse carts or

wagons”.

The Civil-Military Transport

Act set clear fees for the use of civic vehicles. The gratification for the

hiring of single one-horse vehicle, delivered either for the purpose of

transporting of military items, or for the sake of carriage of persons, was set

at the level of 4 silver kopecks for one mile/verst. The remuneration for

single two-horse drawn carts or wagon used for journeys undertaken in order to

develop topographical plans (as well as in cases when it was impossible to

strictly specify “time consumed by the ride itself”), was

established in accordance with the following principles: a) in the case where

the vehicle was in motion within time of up to 7 hours, then one had to pay15

silver kopecks for each hour of use of such transport; b) in the case where

these carts or wagons were hired for more than seven hours, 1 ruble and 12

½ silver kopecks was to be paid for the whole day. Such a solution

referred to the decision of the Administrative Council of June 15/27, 1854,

specifying the fee for the civic vehicles delivered “to supply the

[constant stream of motion, practised in] the stations on postal routes”[31].

In case of persons who have

legitimate right to demand civil transport, for private one-horse vehicles

provided for the carriage of military loads (carried out in the circumstances

described in Article 3 of the law of May 4, 1858), a fee equal to ½ of

the amount of money charged normally for two-horse drawn carts and wagons was

established. It meant the necessity of paying for each one-horse vehicle, the

charge of 2 silver kopecks for each mile/verst. For using three horse

carriages, it was worth paying 6 kopecks for each mile/verst of the voyage.

The tsarist army could demand,

in selected situations and most of all during winter, horse-drawn sledges,

instead of ordinary horse-drawn carts and wagons. In such cases, the fee for

the horse used to pull the sledge had to be paid “as for the typical

vehicle”, that is, it was paid for using one “sleigh horse”

as for an ordinary single-carriage wagon, which is 2 silver kopecks for one

mile/verst. Alternatively, for the two horses running the sleigh, it was

decided to pay as for a typical two-horse vehicle, that is, 4 silver kopeks for

one mile/verst. For three “pulling sleigh” horses, a payment

identical to the one expense established for one “ordinary” double

wagon and one single wagon was made. Finally, for four horses running a sleigh,

it was necessary to pay as for two “double-wagons”. Furthermore, in

exceptional situations, for example, where there was evident lack or shortage

of horses in a given area, it was envisaged to use oxen in their place. The

invading tsarist troops stationed in the Kingdom of Poland usually harnessed a

pair of oxen to carts in such situations, replacing the horses.

Regarding the very process of

payment of fees for civic vehicles, Article 35 of the Act of May 4, 1858,

demanded that the charge for their delivery of the needs of the tsarist army (possibly

also used as transport necessary in other matters related to the functioning of

the Active Army) generally had to be handed over to the carter after the usage

of the horse-drawn cart or wagon (possibly pulled by oxen)[32].

The military authorities issuing

road cards to Russian officers or to other members of the tsarist military

staff were obliged to deliver to the interested persons, an appropriate amount

of money, derived from a general military fund. Subsequently, the official

donor had to ask for the refunding of such a sum from the Main Army

Commissariat. In the case of delegating officers remaining under the management

of the General Quartermaster of the (Active) Army,

the latter donated the money for the voyage “in a way of

promotion”, using his own special fund. Return of money amounts set for

this purpose had to be done immediately after the submission of bills to the

proper military authorities.

For hiring civic

transportation: a) provided for military Russian staff of lower ranks, b)

delivered for sentenced detainees kept in staging areas under the military

custody; c) provided for soldiers escorting these detainees, the fee was

normally not immediately paid and in cash. Instead, the chiefs of staging areas

had to write down appropriate formal receipts. At the “intermediate

stations” (that is, where there were no staging area chiefs functioning),

the same receipts were issued by the chiefs of convoys, transporting the

above-mentioned military/detainees.

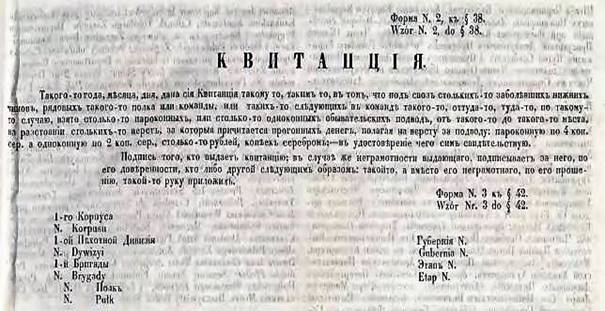

Fig. 2. Receipt for hiring civic transportation,

information concerning issuing, according to the Act of May 4, 1858[33]

Such (as shown above in figure

2) receipts, as well as the “liquidations” submitted by the local

civil authorities, are allocated to

cover the costs of private services done for the sake of transportation of the

Russian (Active) Army, had to be honoured by the local “military

chiefs” (these were commanders of all sort of occupying tsarist army,

stationed on the territory of one gubernia). These gubernial military chiefs

were obliged to send monthly paid receipts to the Main Commission of the

(Active) Army, which was resident in the military stronghold in

Brześć Litewski (Brest), outside the Vienna Congress Kingdom of

Poland. At the same time, they had to pay special attention to the

dating of the receipts sent to the Brześć Litewski receipts. If the

receipts at stake were not sent to the Main Commission of the (Active) Army

within a year from the date of the actual use of their basis of civil

transport, then the payment of the debt by the State Treasury could no longer

take place. This was done under Article 301 placed in the Book III, Part IV of

the Military Declaration Digest[34].

In reference to the above, the

chapter eight of the Civil-Military Transport Act of May 4, 1858, included

detailed information on “funds, from which the fee for the private carts

and wagons were to be paid”. It was found that in most cases, the hiring

expenses for the transportation were to be paid “from the relevant funds,

allocated annually by the State Treasury”. It meant in reality that they

were coming from the budget of the Kingdom of Poland. The appropriate financial

instructions were to be implemented “on the basis of detailed orders of

higher authorities”.

The amounts allocated from

these funds could be distributed only while maintaining the general rules of

accounting and cash accounting in force at that time in the Kingdom of Poland.

Another permanent rule was the necessity to fully comply in this respect with

all legal solutions adopted by the Governmental Committee of Internal and

Spiritual Affairs and in particular with the provisions defining the rules for

granting and determining the number of civic vehicles supplied. In selected

cases as before, the costs of renting transport for military purposes had to be

covered in the first stage by the Main Commissariat of the (Active) Army[35].

Stationed in the stronghold of

Brześć Litewski, the Main Commission of the (Active) Army is

obligated to submit to the above-mentioned provisions laid upon a number of

organisational units of the tsarist army, which had to send at the end of each

month comprehensive bills of expenditure spent for civic transport. Attached to

these bills prepared according to a detailed formula (model No. 3), were

specific road cards. This solution concerned: a) General Quartermaster; b) Main

Commissariat of the Army; c) staffs of corps; d) division staffs; e) staffs of

brigades; f) commanders of fortresses; g) city commanders; h) war governors

stationed in each governorate, i) regimental commanders.

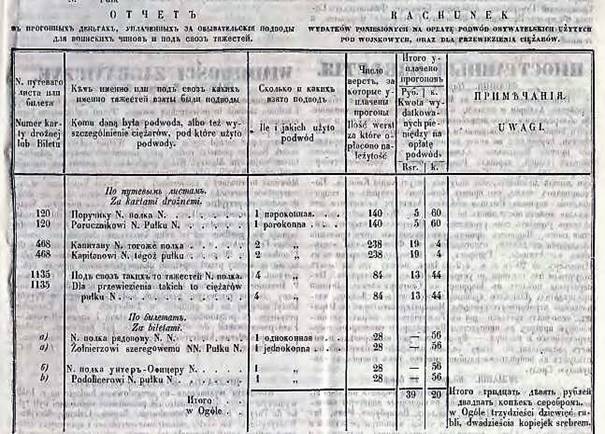

Fig. 3. Receipt for hiring civic

transportation, information concerning expenditures, according to the Act of

May 4, 1858[36]

.

Financial settlements (also

called “liquidations”) of diverse transport funds and hiring of

vehicles bills should contain exact amounts of expenses, covering the whole

period of one month, while “not including” road cards, or other

spending coming from the period of other months. Article 44 of the Act of May

4, 1858 made it clear that every Russian military crossing the border of the

Kingdom of Poland, provided only with a road card authorising him to go one way

to the border point, was solely obliged to return such road card (covering the

last road phase he had travelled in the territory of the Kingdom) “to the

authority from which he had received it”. In the absence of strict

adherence to this provision, he had to, under strict responsibility, return

this road card within two weeks from the moment of arrival at the post, where

(his) regiment was stationed outside the Kingdom of Poland[37]. Finally, it was indisputable

concerning the tsarist authorities that those financial settlements

(“liquidations”) that were not supported by receipts for the use of

civil carts and wagons, as well as bills that were not referenced in specific

road card records, are not generally considered legal and valid, that is, payable.

The

last link in the entire “financial settlement process” of civic

transport duties provided in the Kingdom of Poland for the sake of the Russian

army was their “thorough checking” by the Brześć Main Commission

of the (Active) Army. As previously stated,

although this stronghold and locality were outside the borders of the Vienna

Congress Kingdom of Poland, it was where after receiving the receipts for the

rental of the civic vehicles, the fiscal documentation was finally checked. In

the event that the legality of the evidence was found justified, the relevant

amounts were “separated” and granted as “formal and

irrevocable” funds intended to cover these demands.

In

order to streamline the whole process, and make it subject to the closest

possible control process, the chosen Russian general, Commissary of the

(Active) Army, was to present to the Commander-in-Chief of the whole of the

tsarist military, a kind of detailed financial settlement. Such a list

included: a) the type of military formation applying for quotas for civic

transportation; b) specific amounts of money that have been requested for this

purpose; c) information “in what amount the expenditure for this kind of

activities was found to be fully legal after a due check of receipts”.

The

penultimate chapter of the Civil-Military Transport Act of May 1858 was focused

on penalties for non-compliance with applicable laws. Therefore, Article 47

(the first one in this respect) described the consequences related to the

issuance of road cards and imposed on disposable persons. It was plainly stated

that a military official who had the authority to hand over such travel

documents, and nonetheless was issuing such a card in a manner inconsistent

with the applicable regulations, as a consequence of his unlawful conduct had

to pay a penalty in the exact amount of money that would be in this case

required for formal hiring of a civilian vehicle. In such cases, the amounts

due for the civic transportation were calculated according to postal rates. The

appropriate amount of money was deducted from the wage of the person guilty of

exceeding the provisions, and it was redirected to the fund “to which the

expenditure on the hire of the cart or wagon was due”. These penalties

were imposed when: a) a road card was issued to a person (military), who did

not actually possess the right to use civic transportation; b) in the case of

writing a bigger number of carriages than was prescribed by the regulations in

the road card.

The

financial penalty was also applied to all military personnel who themselves

choose to take up carts or wagons in numbers in excess of the transport service

previously described in the road card. It was also obvious that every

“private person” who illegally took or even falsified the road

card, or who arbitrarily (that is, without the consent and order of the

military authorities) used civil transport: a) was obliged to pay a penalty

equal to the sum normally worth the entire journey; b) was held liable.

The

Act of May 4, 1858, stressed the need for Russian military officers to properly

deal with Polish civilian officials, who were actually delivering to the

disposal of representatives of the tsarist army civil vehicles. According to the

(new) provisions, every military man should behave “politely and

decently”, while applying for/demanding private transportation. The same

attitude must be applied to the relations between the military staff and owners

of carts or wagons, transporting either them or military items. When proven on

the basis of a verbal (written) testimony presented in front of the local civil

authorities, “disorder and violent evasion” were observed and

confirmed, it threatened with severe consequences for those involved in this

“crime” in the Russian military.

The

Article 51 of the transportation law was extremely important, according to it

the regiments of the tsarist army, as well as other military units and all

persons have the right to demand the delivery of civil transport. However, it

does not have the direct binding powers to be independent and simply

“force” on its own, transportation services from local residents.

Thus, the supply of civil transport services could only theoretically take

place with the direct participation of local civilian authorities.

In

order to provide for the local state administration the sufficient time to

prepare the road cards, and most of all to keep the right order in delivering

the vehicles (and especially directing them to the designated location), the

Russian regiments or other military units should have sent their quartermasters

to the representatives of the competent authorities in at least 24 hours in

advance. So in this way of preemptive secondment of military quartermasters to the

seats of local administration enabled quick and efficient conduct of the action

of providing through the local civil authorities, private vehicles for the

tsarist army. It should be

remembered that not all private carts and wagons could be “used”

farther than the nearest staging area. Another important indication was that

civil transport could not be stopped in its march for more than one hour.

In order to fully control all

these restrictions and regulations, a special ledger (pierced and sewn with

thread and sealed at its end) was ordered to be kept at each staging area,

where the number of civic vehicle lifts provided there was recorded. Such a

book was kept in accordance with a special pattern, attached as an Annex

numbered 4 to the text of the bill.

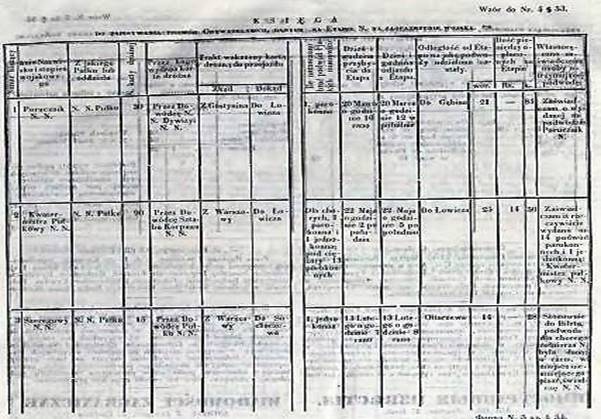

Fig. 4. Page from a

ledger for

writing down civic vehicle lifts, kept at staging areas with information about the

actual process of hiring, according to the Act of May 4, 1858[38]

The last (tenth) part of the

law described here, implemented on the basis of the decision of the

Administrative Council of May 4, 1858, concerned the issue of payment of dues

for providing tsarist armies with private transportation by residents of the

Kingdom. Hence, firstly, it was pointed out that in order to satisfy the citizens

of the Kingdom with a proper (in the original: accurate) collection of fares

for the delivered carts and wagons and perhaps even sledges, local

administrative authorities (that is, presidents, mayors of cities and towns,

and commune administrators) were obliged to maintain a special inspection book

for this purpose. Keeping of this ledger was to be based on the legal basis

created by the decision of the Government Commission for Internal and Spiritual

Affairs of October 3/15, 1845, issued under No. 39 972/20 424 (the sample of

one typical page of this book was attached in this regard to the new law of

1858 as a special Annex, marked with No. 5).

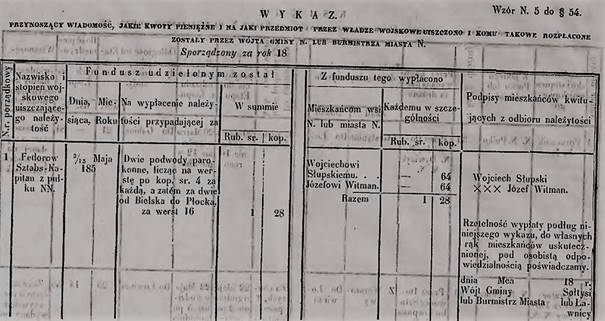

Fig. 5. Page from a

ledger for

writing down civic vehicle lifts, kept at staging areas with information about

expenditures,

according to the Act of May 4, 1858[39]

After the revamping of such a

control ledger by the local chief of the district/poviat, all entries in the

book’s boxes (series of relevant contents) “should have been filled

in with a clear and understandable text”. The relevant writings were to

refer to: a) indication of a military man, paying dues for the use of the civic

transport; b) a detailed description of the funds allocated to the use of such

carts or wagon (including: its formal name; the person for whom it was granted;

the exact amount of money allocated for this specific purpose). The bookkeeper

of the control ledger had to personally ensure that the receipts from the

collection of transport money were signed by the interested persons only. In

case the person driving the private vehicle was illiterate, it was required

that: a) in the cities, the signs (crosses) put up by such an individual were

confirmed by a witness, who could write by himself; b) in the villages,

“in the absence of literate person, the payment had to be executed in the

presence of the village mayors”[40].

When

the tsarist army suddenly and without any previous announcements was about to

pass or was actually passing through towns or villages of the Kingdom of

Poland, of whose march local chiefs of administration did not have any advance

information, interested local presidents and mayors had to immediately notify

the local poviat/district headman about such an event. This information should

be accompanied by a detailed description and calculation of the amount of the

fund left in the area by the various military headquarters to pay for civic

transportation. In reality, the money received was usually “promptly used

to satisfy the residents who delivered the vehicles”[41].

–In

another sense, a form of supervision of the whole process of hiring by the

Russian military Polish civic transport was the introduction of a warrant,

informing that while revising district coffers, poviat chief’s deputies

would also revise ledgers, containing subscriptions for the civic transport. In

addition, they had to obtain the opinions of the local residents, regarding

possible complaints “in the matter of supply of carts and wagons for the

army”. In the case of real problems, the residents’ applications to

investigate complaints were sent back by the deputies of chiefs of district

administration directly to their superiors, for further consideration. In

general (as it was provided in Article 57 of the law act at stake), it was the

duty of the district chiefs of administration to carry out periodic inspections

every six months on the “citizen-transport books”. In the event of

the occurrence of "inaccuracies in control”, or detection of

possible abuse by local authorities, the district chiefs could serve some formal

reminders to persons responsible for any faults and irregularities. The other

option was to initiate criminal proceedings so that persons involved might be

“brought to justice in adequate relation to the level of their

guilt”[42].

3. CONCLUSION

The

maintenance in 1831 in the Kingdom of Poland and subsequent modifications in

the inter-uprising period of provisions concerning civil transport of persons

and goods belonging to the Russian occupation army finally led to the formal

issuance of a new law by the Administrative Council in 1858. The Civil-Military

Transport Act of May 4, 1858, however, contrary to expectations, in principle

(except for a few exceptions) was rather a sort of compilation of already

introduced (sometimes quite long ago) current civil laws and mainly military

regulations. It seems that it could not be otherwise in the conditions of a

quasi-independence. Thus, clarifying and harmonising the existing provisions

and giving them a kind of “Polish administrative dimension”, while

in reality the new law was only a component of a wider process, which become

noticeable after the end of the Crimean War, and was in truth an attempt to

display (ostensibly, and apparently for show mostly) the human face of Moscow's

invading and partitioning power. The most striking manifestation of the dummy

character of changes made would be the steady maintenance of a strange and

unreasonable practice of settling transport quotas, generated from the budget

of the Kingdom of Poland, by a commission, whose headquarters were not located

in the Kingdom itself, but in the "Polish taken away lands",

particularly in the territory directly subdued to Russia, which before the

partition was a part of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

References

1.

Archiwum

Główne Akt Dawnych w Warszawie, Druga

Rada Stanu Królestwa Polskiego: 1834, 1835. Signature: 103, 104, 105. [In

Polish: Central Archives of Historical Record in Warsaw, The Second State Council of Kingdom of

Poland].

2.

Archiwum

Główne Akt Dawnych w Warszawie, Rada

Administracyjna Królestwa Polskiego:1831. Signature: 20. [In Polish:

Central Archives of Historical Record in Warsaw, The Administrative Council of Kingdom of Poland].

3.

”Dziennik Urzędowy

Województwa Mazowieckiego”, January 2, 1832, No 15. Warszawa: Komisja Rządowa

Województwa Mazowieckiego. [In Polish: Official Journal of Mazovian Voivodeship. Warsaw: Commission of

Mazovian Voivodeship].

4.

”Dziennik Urzędowy

Województwa Mazowieckiego”, April 2, 1832, No 29. Appendix Warszawa: Komisja

Rządowa Województwa Mazowieckiego. [In Polish: Official Journal of Mazovian Voivodeship.

Warsaw: Commission of Mazovian Voivodeship].

5.

”Gazeta Rządowa

Królestwa Polskiego”, June 13/25, 1858. No 137. Warszawa: J. Jaworski. [In

Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingom

of Poland, Warsaw: J. Jaworski].

6.

”Gazeta

Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego”, June 14/26, 1858.

No 138. Warszawa: J. Jaworski. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingom of Poland, Warsaw:

J. Jaworski].

7.

”Gazeta

Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego”, June 16/28, 1858.

No 139. Warszawa: J. Jaworski. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingom of Poland, Warsaw:

J. Jaworski].

8.

”Gazeta

Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego”, June 18/30, 1858.

No 140. Warszawa: J. Jaworski. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingom of Poland, Warsaw:

J. Jaworski].

9.

”Gazeta

Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego”, June 19 / July 1,

1858. No 141. Warszawa: J. Jaworski. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingom of Poland, Warsaw:

J. Jaworski].

10. ”Gazeta Rządowa

Królestwa Polskiego”, June 21/ July 3, 1858. No 143. Warszawa: J. Jaworski. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingom of Poland,

Warsaw: J. Jaworski].

11. ”Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta

Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”,

August 16/28, 1835, No. 63. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In

Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of Poland. Saint

Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

12. ”Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta

Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”,

August 20 / September 1, 1835, No. 64. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski.

[In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of Poland. Saint

Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

13. ”Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta

Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”,

August 23 / September 4, 1835, No. 65. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski.

[In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of Poland. Saint

Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

14. ”Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta

Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”,

August 27 / September 8, 1835, No. 66. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski.

[In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of Poland. Saint

Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

15. ”Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta

Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”,

August 30 / September 11, 1835, No. 67. Sankt Petersburg: J.E.

Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of

Poland. Saint Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

16. ”Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta

Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”,

September 3/15, 1835, No. 68. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In

Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of Poland. Saint

Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

17. ”Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta

Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”,

September 6/18, 1835, No. 69. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In

Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of Poland. Saint

Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

18. ”Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta

Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”,

September 10/22, 1835, No. 70. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In

Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of Poland. Saint

Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

19. ”Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta

Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”,

September 13/25, 1835, No. 71. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In

Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of Poland. Saint

Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

20. ”Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta

Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”, September

17/29, 1835, No. 72. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In Polish:

Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of Poland. Saint Petersburg:

J.E. Przecławski].

21. ”Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta

Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”,

September 20 / October 2, 1835, No. 73. Sankt Petersburg: J.E.

Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of

Poland. Saint Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

22. ”Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta

Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”,

September 24 / October 6, 1835, No. 74. Sankt Petersburg: J.E.

Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of

Poland. Saint Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

23.

”Tygodnik

Petersburski. Gazeta Urzędowa Królestwa Polskiego”,

October 1/ 13, 1835, No. 76. Sankt

Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official

Gazette of Kingdom of Poland. Saint Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

Received 11.01.2019; accepted in revised form 30.04.2019

![]()

Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License