Article

citation information:

Rutkowski, M. Education

of members of transport services of tsarist Russia in the 1830s. Admission and

examination of students of the Saint Petersburg Institute of Corps of Engineers

of roads of communication. Scientific Journal of Silesian

University of Technology. Series Transport. 2019, 102, 165-183. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2019.102.14.

Marek RUTKOWSKI[1]

EDUCATION OF MEMBERS OF TRANSPORT SERVICES OF TSARIST RUSSIA IN THE 1830S. ADMISSION AND EXAMINATION OF STUDENTS OF THE SAINT PETERSBURG INSTITUTE OF CORPS OF ENGINEERS OF ROADS OF COMMUNICATION

Summary. This paper focuses on the

phenomenon of the strongly complicated process of education of cadets and

officers of tsarist transportation services corps during the 1830s of the 19th

century. While primarily commencing this short study with introduction and

changes in the didactic process occurring in Saint Petersburg Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication at the early

stages of its development, the main scope of the research was to describe: a)

changes and restriction in the accessibility to the very process of education

given in this Institute, b) the alteration in the formal entry and most of all

scientific requirements. c) the outcome and circumstances of final

examinations, all happening during the third decade of 19th century.

Keywords: tsarist transportation, Russian

Empire, administration structures, 19th century

1. A SHORT OUTLINE OF

CHANGES IN DIDACTIC PROCESS CONDUCTED AT THE INSTITUTE OF CORPS OF ENGINEERS OF

ROADS OF COMMUNICATION UNTIL THE BEGINNINGS OF 1830s.

It was on

November 1/13, 1810, when the so-called Institute of Corps of Engineers of

Roads of Communication started its formal activity, as the opening of this

educational institution took place in the presence of tsarist Chief Director of

Roads of Communication, Prince Georg of Oldenburg[2]. At the

same time, 30 students were admitted to this institute in

order to commence pursuing a three-year teaching course.

The

assumption was that after completing the first year of teaching, those of the

students who were considered as "worthy of further promotions"

received the (military) rank of ensign, after

completing the second year of education, they became second lieutenants, in the

third year of their studies, they went on to active duty as engineering

lieutenants. In the initial period of the Institute's activity, the number of

subjects taught there was not very staggering. First of all, they taught at the

St. Petersburg Road and Engineering School: a) the foundations of

“elementary mathematics”, b) rules for drawing of plans, c)

descriptive geometry, d) “shadow theory”, e)

statistics, f) rules for the construction of vaults, g)

basics of drawing, and finally, h) rules

for “breaking of stones”.

After a short period of time, it turned out that the whole lecture

course prepared in this capacity did not meet the specific requirements,

imposed on the then Russian road construction process, their infrastructure,

guidance as well as supervision rules. In this connection, the following

lectures were added to the original basic teaching programme: a)

“integral calculi”, b) differential calculi, c) the practice of

applying of descriptive geometry, d) dynamics, e) construction, f) physics, g)

chemistry, h) mineralogy, and i) science of fortifications. The changes

introduced, of course, resulted in the fact that the current three-year course

of study was transformed into a four-year training system. The students

themselves were divided into four “sections” (in other words:

“brigades”); a) the first “section” included second

lieutenants (French: sou-lieutenents), b) all ensigns (French: enseignes) were enrolled in the second “brigade”, c) the students of

the first year (French:eléves) were included in the third “section”, and finally d) to

the fourth “brigade" the whole of second grade students were

included (French: surnuméraires)[3].

Later on, namely in 1822, the general course of teachings at the

Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication was extended to

include lectures; a) “on carpentry”, b) “on drawing

cards/plans”, c) “gnomony” [gnomoniké

téchne], d) applied mechanics, e) general

construction, f) beginnings of tactics, g) science of artillery, and finally

(h) science of strategy. Starting from 1824, students of the Institute who did

not possess officer degrees (namely: cadets) were living obligatory in the

campus of the university. Initially, the number of such cadets was 72. Out of

the whole number of them, 40 individuals received government scholarships, and

the remaining 32 people paid for themselves the costs of their education,

maintenance, etc. The latter were called so-called “pension

students”.

Then a new category of students soon

appeared in St. Petersburg’s Road Institute. The reason for it was that

within the tsarist Communication Corps was then created a separate section,

which received the name of “a branch of military builders”. For the

creation of a new category of persons who were counted among members of the

Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication, stood a sort of pressing need for

active use in the conduction of actual road construction process even the

“learners”, who were still studying as future-to-be transportation

officers. They were those officers who were “not so much advanced in the

teachings, as persons still studying /…/, [but who] could usefully be

used to carry out works and constructions”.

In view of the above, in the early 1820s, one more transportation school

was established in St. Petersburg, teaching in a way of two-year course study,

the future employees of Russian road engineering services. This institution was

called the School of Builders. Originally, it was agreed to accept into a new

teaching unit a 100 students, who having graduated from this university,

received the (military) rank of an ensign. To the Institute of Corps of

Engineers of Roads of Communication

itself, this was initially important as far as the most talented of those

ensigns were then given permission to continue their education at the

Institute. Of course, having received the ranks of officers, they were

permitted at the Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication to

sit in the class intended for ensigns and after showing proper progress in science,

they were directed to an engineering course, where they could learn together

with the students (the Institute's officers)[4].

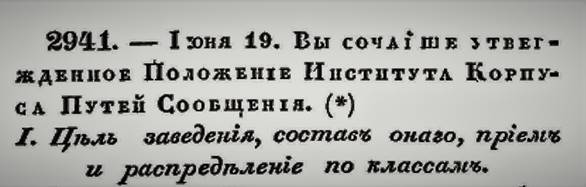

Subsequently, in 1829, Tsar Nicholas I approved a new law on the

Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication[5].

Fig. 1. The introduction of Tsar Nicholas I’s law of 19 June / 1

July 1829 on the Institute of Corps of Engineers of Communication[6]

As a consequence, the Institute of Engineers of Corps of Roads of

Communication received a new organisational form at the turn of the twenties

and thirties of the nineteenth century, although the university was still under

the management of its director, supported by two of its direct assistants. One

of them was solely responsible for scientific issues only, the other took care

for economic issues, as well as for the supervision of any criminal cases at

the Institute.

At the time, the teaching corps employed by the Institute consisted

essentially of 15 professors. Among them were both the land and water

communication officers, and members of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences,

and “other first-class [science] institutions”. The total number of

professors had to be increased at that time by 6 auxiliary professors. The

overall composition of the teaching staff of the Institute also included 24

so-called “correspondents”, officers of the Corps of Engineers of

Roads of Communication. At St. Petersburg Road Academy, the following

additionary members of teaching staff were still employed; a) head of the

workshop, b) people assisting in the construction of models, c) two Russian

language teachers, d) two teachers of French language, e) a teacher of military

code, f) “instructor of horse riding, drawings and gymnastics”[7].

It is extremely important to notice here, that the changes made in the

aftermath of introducing of new legal solutions included the process of

absorbing the Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication,

mentioned above, the St. Petersburg School of Builders. It happened that from

that point in time within the walls of the transportation university, they

automatically became students, who would be encountered as; a) cadets, b)

ensigns, and c) officers. At the same time, the structure of the Institute's

education system was broadened, extending the curriculum by two new classes,

that is, the fifth grade and the sixth grade, which could be considered (for

example, by Alexander de Krusenstern) as sort of preparatory classes for

commencing proper study. As a result of applying these solutions; a) the cadets

were now learning in the fourth, fifth and sixth class of the Institute; b) in

the third class ‘the sciences was taken” by officer cadets, (c)

ensigns learned in the second grade, and d) in the first class “science

was learnt” by second lieutenants[8].

In connection with the introduced organisational changes, and in

particular reference to the re-evaluation of the structure of the teaching

process itself, the scope of the whole educational programme given at the St.

Petersburg Institute of Corps of

Engineers of Roads of Communication was substantially changed. Specifically, in

the fifth and sixth grades of the Institute the cadets had to learn; a) the

basics (grammatical rules) of Russian and French languages, b) universal

history, c) geography, d) the basics of mathematics, that is, arithmetic and

algebra, e) geometry, and f) calligraphy.

In the fourth grade, the curriculum was of course expanded. It was

necessary to learn at this level; a) Russian grammar, b) Russian geography, c)

Russian hydrography, d) a set of “mathematical sciences” (including

the repetition of the material being already processed and the completion of

knowledge in the field of algebra), e) “both sciences of

trigonometry”, f) ability to use geodetic tools, g) drawing up plans, h)

mineralogy, i) analytic geometry, j) descriptive geometry, k) “shadows

theory”, l) linear perspective, m) the basics of different architectural

styles, and finally, n) elementary tactics.

During the teaching course in the third grade of the Institute, the

following subjects were conducted; a) the military code, b) the basics of

French literature, c) “synthetic statistics”, d) differential

calculus and integral calculus, e) “use of descriptive geometry for

hewing stones and carpentry”, f) “the first part of the art of the

building” (where knowledge of building materials should be mastered), g)

“land communications”, h) stonework and mural works, i)

architecture in the field of “building details”, and embellishing

edifices decorations, j) drawing, k) “coloring”, l) an extended

history of Russia, m) statistics of the Russian Empire and n) learning about

artillery and field fortifications.

In turn, in the second class, the curriculum included; a) a lecture on

the development of French literature, b) mechanics ( whose “science”

consisted of analytical lectures in the field of: statistics, hydrostatics,

dynamics and hydrodynamics), c) physics, d) “application of descriptive

geometry to the mapping system, gnomony, and air perspective”, e)

“construction of buildings prepared by means of an academic

competition”, f) the second part of building science (which included:

lectures on bridges, water transport, sailing on lakes, sailing on canals), g)

science of “permanent fortifications”, h) lava drawing, and i)

coloured drawing.

The final, first-class of St. Petersburg Institute of Corps of Engineers

of Roads of Communication had in its curriculum; a) “mastering of the

official style correspondence”, b) lecture on “world system and

higher geodesy”, b) strategy, c) history and literature in the field of

“skills”, d) “collection of art of all kinds of

building”, e) applied mechanics, f) chemistry, g) mineralogy, and

finally, h) creating projects (and their detailed descriptions) in the field

of: civil architecture, road architecture, canal architecture, hydraulic works,

and machine construction.

In addition, during the studies at the Institute it was obligatory to

learn horse riding and gymnastics, as well as perform regular military

exercises. The Institute's teaching programme apparently included some

religious issues. For cadets and officer cadets, “the principles of

religion and Christian morality" were lectured by three different

clergymen, representing "Russian-Greek" (Orthodox), Roman Catholic

and Protestant faiths. Finally, it should be noted here that the general

process of “physical and moral education” of all the students of

the Institute was consistent with the principles in force in all tsarist cadets

corporations[9].

At the turn of the twenties and thirties of the nineteenth

century, approximately 250 pupils studied at the St. Petersburg Institute of

Engineers of Roads of Communication, of course, these data have changed

periodically. And so, in 1829, there was a total number of 240 students of the

Institute, of which 160 were sponsored by the state, and 80 received education

at their own expense[10]. In turn, Krusenstern gave in his publication from the epoch that

(apparently during another university year) 265 of students of road engineering

were studying there. 160 of these people received education at the expense of

the state, while 105 more people studied, covering all their expenses in the

amount of 1,200 rubles a year (including tuition) from their own funds. These

data indicate, however, that at least the number of Institute students

supported wholly by the state, that is, 160 persons, remained unchanged in this

period. It should also be remembered that every year the Russian State Treasury

allocated 192 thousand rubles to the maintenance of the St. Petersburg

Transportation Academy[11].

2. CHANGES IN ACCESS TO EDUCATION AT THE INSTITUTE OF

ENGINEERS OF ROADS OF COMMUNICATION INTRODUCED IN THE EARLY 1830S.

Although in the 1830s, the internal structure of the Institute and its

general way of governance did not change profoundly (perhaps except the shift

in the position of its director, General-Lieutenant Bazen, who resigned from

his position on September 5 /17 September, 1835)[12], this period marked the appearance of a whole range of extremely

important decisions regarding the recruitment of candidates for the tsarist

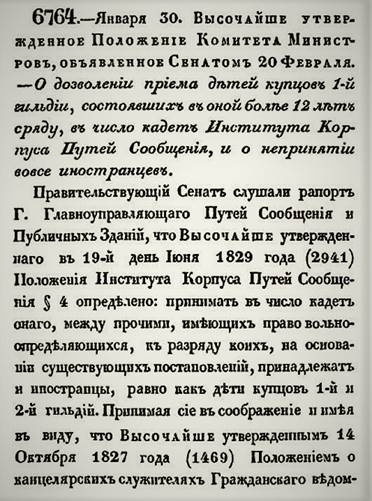

Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communications. The first of these

was the introduction of two significant personal restrictions in the

accessibility to the learning process at this Institute. Thus, at the request

of the managing chief of the Department of Roads of Communication and Public

Edifices, Carl Wilhelm von Toll (who embraced this position on October 1/13,

1833[13]), as well as on the basis of the opinion given by the St. Petersburg

Committee of Ministers, dated as of January 16/28 and January 30 / February 11,

1834, Tsar Nicholas I decided to change some of the solutions in these matters,

basing on the existing laws. In this case, it was about; a) the law on clerks

from October 14/26, 1827, and b) the Act on the Institute of Corps of Engineers

of Roads of Communication itself, approved by Nicholas I on June 19/July 1,

1829, and then published by the decision of the Governing Senate, dated as of September

1/13, 1829[14].

On the basis of the unitary monarch's decision, therefore, only the sons

of Russian merchants belonging to the so-called most important First Merchant

Guild for at least the uninterrupted period of the twelve preceding years were

now entitled to enrol on the list of students of this Institute (in other

words, it meant that sons of other merchants, etc., were automatically deprived

of their right to study there). Furthermore, their education process itself had

to be paid in principle, from private sources only, which of course excluded

any state subsidy in their cases. On the other hand, it was much more important

to introduce, simultaneously, a categorical ban on allowing foreigners to the

St Petersburg Transportation Institute, who “henceforth neither with the

financial support of the state nor at their own expense, had to be admitted [to

the Institute]”. After being accepted by Tsar on January 30/February 11,

1834, the formal law in these matters has been issued by the 1st Department of Governing

Senate on February 20/March 4, 1834[15].

However, not all of the regulations on accessibility to the teaching

process at the St. Petersburg Communication Institute issued at that time were strictly

restrictive in nature. It should be noted, though, that on November 27/December

9, 1836, the Russian Governing Senate issued an ordinance, under which it was

decided to give access to the Corps of Roads of Communication for the sons of

persons possessing the right to hereditary nobility, obtained thanks to their

participation in the tsarist administration structure, while having the high

official ranks. Now they were able to join the Corps of Engineers of Roads of

Communications, holding the rights of “volunteers or freelancers”[16]. Such a possibility, of course, also assumed the right to study at the

St. Petersburg Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication

Fig. 2. The legal proposal of the Russian Committee of Ministers

regarding restriction of admission to the Institute of Corps of Road of

communications, approved by Nicholas I on January 30/February 11, 1834 and then

made available to the public based on the ruling made by the First Department

of the Governing Senate on February 20/March 4, 1834

(the first verses)[17]

3. RULES FOR ADMITTING STUDENTS “AT TREASURY

EXPANSE” TO THE INSTITUTE OF CORPS OF ENGINEERS OF ROADS OF COMMUNICATION

IN SAINT PETERSBURG, ANNOUNCED IN 1834 AND 1835.

The state authorities usually publicly announced the conditions to be

met by candidates in order to be allowed entry into the ranks of students of

the St. Petersburg Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication[18]. In the 1830s, some announcements were still distributed in the Russian

Empire, as well as on the territory of Vienna Congress Kingdom of Poland, later

crushed and conquered by the Tsardom in Russian-Polish war of 1831. And so, in

the middle of April 1834, such issued by the Institute announcements, regarding

the possibility of becoming a student of this academy by acquiring a state

scholarship, appeared in the press (in short form).

The date of the anticipated exam was set for the day of May 15/27, 1834.

At the same time, the announcement issued in the spring of 1834 by the

Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication contained a detailed

description of the conditions for admission into the school. The primary

organisational provisions of this teaching unit, finally approved by virtue of

the decision of Alexander I of June 19/31, 1820, were regarded as the guiding

principle, from which it was clear that in the Institute cadets were accepted

annually. However, in order to gain full admission, one had to first go through

the one-year preparatory course.

The obvious boundary condition for obtaining the right to enter the

Institute as a cadet was to be in the age group of at least 14 and 18 years

old, being at the same time of “healthy complexion [of skin]”. Each

candidate had to pass in the so-called “Institute conference” area,

an appropriate exam, prepared to check his actual “scientific

knowledge”. In addition, it was argued that young boys/men joining the

Institute were expected to have relevant knowledge in the fields of; a)

(Christian) religion, “according to their faith”, b) grammar of the

Russian language, c) grammar of the French language, d) universal history, and

e) general geography. In particular, an emphasis was put on the knowledge of

Russian history and geography as well as of arithmetic and drawing.

In the spring of 1834, it was identified in great detail, the social

categories from which the candidates for the cadets of the transport services

may come. Hence, it turned out that first of all (which was nevertheless quite

obvious) were accepted into the Institute children of nobility, staff officers and

senior officers, and people with the right to free admission to universities.

In the latter case, however, a restriction was introduced relating to the

exclusion from the privilege of children of merchants belonging to the 2nd

Guild as well as of foreigners. It was due to the fact that, under the two

decisions of the St. Petersburg Committee of Ministers, representatives of both

groups could no longer join the Institute ( see text above)[19].

There were differences in the scope of the necessary documentation

required for joining the St. Petersburg Transport Scientific Institution.

Firstly, on the basis of the implementation of the provisions of the

Russian State Council, then confirmed by Nicholas on February 6/18, 1828, the

nobility children had to provide copies of the “Nobility Deduction

Units” protocols, on the basis of which they were recognised as nobles

(“dvorianie”). On the other hand were; a) sons of staff officers

and senior officers coming from the nobility, whose fathers served in the army

and on their own request were dismissed, and b) sons of officials of ranks or

classes appropriate to the officer's ranks in the army, should have to submit

their father's passports. In such a passport, there must have been written a

precise description of their service, of course, signed by the military or

civilian authorities under which their fathers served. In turn, the children of

fathers still performing their duties as staff officers and senior officers and

their respective civil servants were obliged to submit descriptions of the

service of their fathers, signed by their “present” superiors. It

was a permanent rule that it was always necessary to submit together with other

documents, the baptism certificates signed by the right consistory.

Secondly, the Institute's authorities analysed in detail and made public

the arrangements for admission to study at the St. Petersburg School of

Transport for children of persons with the right to free admission to all of

the Russian schools/colleges. First of all, it was about the youth of fathers

who have the only so-called personal (that is, attached to a specific

individual) nobility. Namely, this concerned primarily and mainly, the sons of

senior officers who did not come from the nobility, and who did not acquire

their rank while serving in their own regiments, but who finally received it

while resigning from their post in the Active Army. At the same time, quite

similar or identical situation concerned the children of these senior officers,

who “had got this rank during their activity in civil service /…/

but not from the military service”. According to the sentence expressed

by the Russian Council of State, then further confirmed by Nicholas I on

February 6/18, 1828, these categories of candidates should have submitted

identical evidence similar to those provided for the children of the

“standard” senior officers. Also in these cases, of course, there

was the pressing need to provide baptism records.

Thirdly, the announcement of the conditions for joining the Institute

Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication examined in detail, the rights of

children of the clergy of different rites. It was indicated then that - in

accordance with the laws of May 3/15, 1818; June 25 / July 7, 1827, as well as

of January 26/February 8 and December 14/26, 1829; a) sons of the Orthodox (in

the original "Greek-Russian faith") priests and deacons, b) children

of Protestant pastors, c) the sons of priests and deacons of the Uniate Church

(that is, of the Eastern Catholic Church on the territory of the former

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, accepting the supremacy of Sedes Apostolica

Romana), and finally d) male children of clergy of Armenian Church were all

obliged to submit certificates issued by local clergy authorities, allowing

them to enter the public service. In addition, these clergy sons were forced to

submit graduation certificates from at least the “middle section”

of the seminar.Additionally, it was necessary to prove that these prospective

transportation students were not released from further seminary education

because of any kind of “flaws”. Finally, it was fitting to deliver

their birth certificates, confirming that they were born at a time when their

fathers had already been ordained. In turn, the children of male Protestant

pastors had to submit, issued by the Council of Livonian and Estonian Affairs,

confirmation of lack of obstacles in accepting them to the transport services

of the Russian state.

The legislation, moreover, introduced partly similar restrictions of a

general nature. Thus, candidates to the Institute were reminded of the principle

that was previously introduced by the Act of December 5/17, 1802, on the basis

on which there were entitled to free admission to study; a) university students

(so-called “academics”), b) graduates of the Imperial Academy of

Fine Arts in St. Petersburg, as well as c) alumni of all scientific

institutions of the Empire with a special privilege status, but only if they

were able to submit certificates of completion of acquired so far sciences and

all the rights acquired for this reason.

Because, finally, according to the new regulations, only those children

of merchants whose fathers had been in the 1st Guild for at least 12 years were

allowed to enter the Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication,

moreover, they had to submit the relevant certificates from the city councils

and magistrates. These certificates were not only meant to concern their

fathers but should also include the consent of the local merchant trade union

to exempt those candidates to study at the Institute from the obligation to

perform military service, the usual duration at the time was 25 years. Such

credentials were also to confirm the payment of tax for them. Another

requirement imposed on the children of merchants was the necessity to present

written by their consistory their “full-fledged” (that is, given in

a legitimate way) births[20].

Here it is worth noting that candidates wishing to join the Institute by

paying their tuition themselves, were obliged to pay for half-yearly education

fee in advance (600 rubles). In addition, a kind of warranty, signed by several

"trustworthy" citizens permanently residing in St. Petersburg, must

have been provided in such cases. Such an attestation had to include an

annotation about ensuring a successive payment of tuition fees, which would be

the responsibility of the guarantors themselves.

It was a general rule that each candidate, joining the Institute of

Engineers of Corps of Roads of Communication under the age of 17, should have

attached to his application a sort of confirmation (the so-called

“attestat”) issued by a scholarly institution, school or private

tutor, informing where and what he has taught accurately so far. Such

attestation was accompanied by a certificate of “good condition of his

manners and behaviour”. In the case of people who were 18 years old, the

candidates in question were obliged to deliver an issued certificate by the

local civil governor of their “conduct” for the duration of their stay

in the place where they had previously lived. The way they behaved had to be

“advantageous” (worthy of recommendation or praise), and any of the

future students of the communication routes could not be “censored”

(suspect) for any wrongdoing. In addition, candidates were required to provide

a certificate of vaccination against smallpox. What was also needed was a

certificate of civil authority about having or not, by the candidate himself or

his parents of any immovable property, that is, “estates or

houses”. It was evident that the records, prepared in foreign languages,

as well as the official documents of “diligence”, had to be sent

along with the appropriate translation into Russian. Such a translation had to

be certified in an official form[21].

Parents, relatives or guardians directly send their

applications for admission of young prospective students to the Corps of

Engineers of Roads of Communications to the director of the Institute, even if

these letters were formally addressed to the Tsar, himself (sic). Parents who

applied for admission of their sons to the Institute at the whole expense of

the state, nonetheless should have brought them (in the original “get

them transported”) to St. Petersburg headquarters of the Institute, in

order to allow them to participate in conducting the entrance examination within

the university buildings. Among the different lines of the announcement at

stake, one could find a very specific statement, as there was placed in the

following part of a script, information referring to rather an imprecise

limitation of the number of people accepted at the time to the Institute. In

fact, from among the young people coming for such an examination, only as many

students could enter the St. Petersburg Transportation School walls as there

were vacancies available at the given time. Of course, this unsteady number of

vacancies could depend on many changing and in principle, arbitrary conditions.

Actually, the decisive factor (at least formally) of

admission to the ranks of the Institute's students was the very result of a

comprehensive examination carried out on all of the required subjects, which

meant that there were accepted “not differently than on the basis of

obtaining the majority of points in the exam”.

Some

exceptional situations were anticipated here. And so, prospective candidate receiving

good results on the exam, and fulfilling any other additional requirements of a

prospective student who, however, due to the lack of adequate vacancies did not

enter the group of students of the Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of

Communication in the given year, at the same time acquired automatically the

right to free access to this university before all other persons trying to

enter the following year. However, this could only happen “after being

proved on the second exam that the [given candidate] would have potentially

made [in the meantime] bigger progress, and therefore can enter the higher

class than he could have possibly entered the previous year”.

Finally, the ordinance of mid-April 1834 indicated

that a student upon completing the whole of his “scientific

courses”, which at the time meant the awarding of the rank of lieutenant

in the Corps of the Engineers of Roads of Transportation, could be transferred

to the civil service, holding rights to the rank available in state civil administration,

granted normally and usually to students ending typical university education.

Another indication of a legal caveat (written in the article no 12. of the

regulation described here) was the statement about the inalienable need for

extending by graduates, completing educational courses at the Institute of

Corps of Roads of Communication on the principle of obtaining of a government

scholarship, at least ten years of work done “under the knowledge of the

Corps". The only acceptable derogation was the discovery of the graduate

with a non-cured disease[22].

Also in the following year of 1835, specific

regulations were announced, defining the rules for joining the initial

verification for membership itself at the St. Petersburg Institute of Engineers

of Corps of Roads of Communication[23]. So similarly as in the previous year, - in

accordance with the announcements published in the official press, the

authorities of Institute gave the general public the possibility of getting

knowledge on the conditions of entering into this scientific institution for a

number of new cadets.

The deadline for sending applications along with the

necessary documents was fixed for May 15/27 1835, and the date of the

examination was set at June 1/13 of the same year. Of course, those candidates,

who possibly would send their applications after the deadline, could not take

the verification exam in the given year[24].

As these announcements were also published in the

subjugated Kingdom of Poland, hence, apart from the appearance of a number of

supplements in the description of the required knowledge and some formal and

administrative changes, one could trace, however, a significant difference in

both notices. Well, the announcement published in the Kingdom of Poland in 1835

contained at the same time a list of textbooks, which were normally used at the

level of education taught in individual classes of the Institute of Corps of

Engineers of Roads of Communication. The purpose of adding to this list of

books was to bring about such a situation “when these [individuals] wishing

to enter one of this (that is, Institute] classes could use them to preserve

monotony in the scientific system” [25].

A comparison of the two lists of admission requirements to the St.

Petersburg Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication in 1834

and 1835 (when a number of requirements have been clarified, especially of a

formal nature) indicates according to the author of this text, the persistence

of relatively unchanged tendencies in respect of the "scientific"

issues, that is, the then relative stabilization as to the initial educational

expectations of prospective students. The other tendency observed would be the

progressive stiffening or formalisation, and, above all, the specification of

administrative requirements.

In addition to this, there was a significant factor in the unification

nature of the tsarist transportation educational system of the time. At that

time, these authorities officially recognised the need to clearly indicate

which textbooks the prospective candidates were to study and prepare for exams

from, while coming from outside the strictly Russian educational circle, but

still being subjugated to Russian power[26].

4. FINAL EXAMS AT THE INSTITUTE OF CORPS OF ENGINEERS

OF ROADS OF COMMUNICATION IN 1834, 1836 AND 1837

An important supplement to the image of educational practice carried out

at the St. Petersburg Institute of Engineers of Corps of Roads Engineers in the

1830s is the analysis, available in relation to the source information given in

the form of published press reports of final exam sessions, conducted in this

transport school in the period of our interest. The data available for the

years 1834, 1836 and 1837 in the form of formally published reports are

presented below.

Beginning the description of this process, one should

focus on the events that took place at the Institute on May 3/15, 1834, when a

proper examination was carried out in the presence and with the personal

participation of general-adjutant count Carl Wilhelm von Toll, Chief of the Department of Roads of Communication

and Public Edifices of the Russian Empire. In addition, during the exam itself,

there were present in the congress hall “a large audience of

science-bound scholars”. The rule was that not only members of the Institute

questioned the examined students, but the so-called audience was inspired to do

the same, and this was because asking of various questions was supposedly

encouraged. Of course, the content of these questions must match the criteria

of “course subjects”.

It can also be argued from the description that the

overall exam result was more than successful, because "it was not possible

to disagree about the accuracy and an exactness that the responses [of the

students] were characterised with”.

It should also be added that one of the important and

formal parts of the whole “examination ceremony” was the reading of

a special speech on the progress of road construction in tsarist Russia,

prepared especially for this occasion by the then director of the Institute: General-lieutenant

Bazaine[27].

However, the whole ceremony did not end there. At a

later stage, the gathered guests (in the original: “the gathering of

audience”) were guided by Count Toll through selected rooms of the

Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication. Particularly

interesting were the lecture rooms, where a large number of drawings of the

cadets were displayed for inspection, etc. In addition, the visitors had the

opportunity to see selected scientific (storage) cabinets located in the

Academy such as; a) the physician's cabinet, and b) the cabinet in which a set

of various models have been placed. As this was underlined in the formal

description of the whole event, the visitors additionally saw “all the

belongings of the teaching institution, so beautifully maintained and

abundantly supplied” in general[28].

Another public exam of transportation students about which we possess

published data took place at the Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of

Transportation on May 5/17, 1836. Similarly, as in 1834, this event took place

in the presence of Count Toll, and “a large group of high officials,

distinguished individuals and members of the Academy of Sciences”. The

questions asked by these people concerned various issues related to the entire

curriculum in force. The result of the exam exceeded as usual “expectations”.

An enthusiastic opinion found in the press article from 1836 indicates that the

exam “was a new proof of the usual progress of the Institute, rightly for

the greater part attributed to the care of the enlightened superiors who have

so far led it”. While describing the level of answers given by students

which were assessed as clear, accurate, and being of logical integrity. This,

in turn, was supposed to be an exact proof of the “usefulness of the

methods that were kept” by the lecturers and teachers working at the

Institute. Needless to say, not all of these teachers were employed at the

Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication as their primary

place of work. Namely, some of them worked full-time at the tsar’s

Academy of Sciences and as well as at the University of St. Petersburg.

During part of the exam, but before the final examination of the

officers’ class students, the director of this “teaching and

research institute”, General Potier, gave a laudatory speech. In proper

reference to the situation, words of Potier; a) described the methodology of

the curriculum, b) presented “an image of the student's behaviour”,

c) outlined the teaching duties of the Institute's teachers.

Subsequently, Count Toll found himself again as a guide to the

Institute, leading, as he did two years ago, gathered publicity members through

the individual halls, where various drawings, plans and projects were

displayed. Then, the Institute's physical cabinet and the model gallery were

visited. The latter has in the meantime been supplemented with “models of

iron roads” and the dome of the Saint Petersburg church of the Holy

Trinity. To further raise both the level of interest of those present in the

whole event, as well as in the Institute's activity itself, Count Toll also

decided to give his own personal lecture, describing this time various

“hydrographic” systems.

Even if at first glance everything was almost quite the same as before, nevertheless

in 1836 a significant change occurred in the description of the whole ceremony.

It was then that it was noted that “the congregation was pleased to see

that there were added quite many new subjects [of teaching], closely linked

with the main skills, especially the moral history of the same teachings, that

were so great grown in this Institute”.

It was also noted with an obvious recognition that “hence the care

and foresight of some expert persons who are entrusted with [guidance of] the

direction and maintenance of the Institute, do not neglect anything that may

make it worthy of their purpose, the purpose of education for the service /..

/of capable engineers and faithful [tsarist] subjects”[29].

Finally, in the next year of 1837, the public exam of the students of

the Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication took place on May

3/15. As before, it was held in the presence of general-adjutant Count Toll and

the so-called “gathering, as numerous as great”, which composed at the

time of; a) the president of the St. Petersburg State Council, b) the

ambassador of the French king, and c) other “persons belonging to the

diplomatic body”. Surprisingly, this time the answers given by the cadets

and selected student-officers were merely regarded as

“satisfactory”. However, this educational collapse was to some

extent alleviated by the assessment of the answers given by some

student-officers, who passed their exam with answers that “proved their

great progress in the sciences”. This year (as it was, by the way, the

twenty-fifth “release” of adepts in the history of the described

St. Petersburg Academy), as many as 33 ensigns and 36 second-lieutenants (69

people in total) were deemed worthy of increasing in their ranks and referring

to work directly in active service.

After completing the examination part of the event, General Gottmann

(formerly a student, became director of the Academy from October 1836)

presented a short speech, in which he outlined “the reasons of the

progress that this [Institute] may rightly boast of”. In addition,

Gottmann also directed his words to the students who were about to leave the

university walls, making observations about their obligations to the Tsar and

the fatherland.

Next, in the company of Count Toll, a traditional visit was made by the

guests to selected rooms and cabinets of the Institute of Corps of Engineers of

Roads of Communication, where they had put on public display; a) the best

drawings and plans made by students, and b) some scientific archives. As usual,

special attention was paid to the cabinets: physical, mineralogical and of

models, where it was not without pride, that the occurrence of “variety

of objects, their great number, [and] their wealth and perfection [of their]

craftsmanship” was noticed[30].

So as one can see, a typical description of the examination of adepts of

St. Petersburg Transport Academy during the 1830s in a way consisted of three

quasi-independent parts. Above all, the examination of the cadet or officers

itself was described generally and briefly, as were the results obtained in

this respect. In addition, there was a customary description of the speech

given by the current director of the Institute. Typically, it was also

emphasised in these reports the custom of “touring” the guests

around the Institute's rooms and cabinets by the Russian “minister of

transport” - Count Carl Wilhelm von Toll.

Fig. 3. Bolesław Skirmunt, Polish nationality cadet of tsarist Corps

of Engineers of Roads of Communication as depicted in 1833[31]

Finally, it is worth noting that, although foreigners had finally been

banned from joining the St. Petersburg Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads

of Communication, this did not apply to Poles, living after partitions of the

Republic within the boundaries of the extended Muscovite Imperium. Plus it

should also be recalled that after the November Uprising of 1831, they no

longer had the opportunity to study in the colleges of the Congress of Vienna,

Kingdom of Poland. For these two reasons, we are provided with some partial

evidence (given for one year really) of recorded promotions of Pole students of

the St. Petersburg Transport Academy.

Hence the year of 1836 turned out to be particularly important in this

aspect, because at that time significantly, a lot of Poles received promotions

(after completing the public exam), as considerable data on this subject

appeared in official reports, available in form of press reports distributed in

the Kingdom. As a result, it can be noted that the following people of Polish

nationality and descent, students of the tsarist Corps of Engineers of Roads of

Communication, obtained by order of Nicholas I of May 27/June 8, 1836

“elevation in ranks”. Among them, there were, first of all, the

second lieutenants: Krassowski, Strokowskski and Brzeziński, who were

nominated as lieutenants. Further appropriate nominations for the rank of

second lieutenants were obtained by the ensigns: Kieberdź and Smolikowski

(in the future both of them became chiefs of the Departments of Roads of

Communication/Land and Water Communications of the Russian Empire and the

Kingdom of Poland), Suchodolski, Szymański, Zbrożek, Jowiec,

Jerzemski, Hryniewicz, Sakowski and Horodecki. In turn, the following Polish

non-commissioned officers were appointed to the rank of ensigns: Karol

Napierski, Bronisław Slizień, Michał Bohomolec, Alexander

Hłasko, Edward Brzezinski, Augustyn Zaleski, Aleksander Matusiewicz and

Prince Józef Drucki-Lubecki (apparently coming from famous Polish

aristocratic family, whose representatives played important roles in the

Russian-Polish relation of that time)[32].

As can be seen from the obtained selective data, Poles constituted a

decidedly over representative percentage figure of the students of the

Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication, raised in ranks in

the mid of 1830s, especially in relation to second lieutenants and ensigns. For

example, the number can be estimated as 18 to69, (for 1836), which in practice

accounted for approximately 26% of all promotions. It is difficult, however, to

assess whether this relationship persisted throughout the whole of the 1830s,

especially when one considers the political turmoil of that period and the

general attitude of the invading Muscovite State to the Polish in question. On

the other hand, however, it should be recollected that huge personnel shortages

existed in the transport services of the Russian Empire at that time, which

could have made possible blocking measures as counterproductive ones. This

thesis is supported by Tsar Nicholas’s decision of June of 1832,

incorporating the Kingdom of Poland’s transportation engineering services

staff into the official administrative structures of the Russian Empire[33]. Even so, it would be an extremely rare case where the official tsarist

policy in some sense co-operated with the bottom-up attitude of the Polish

society.

5. Conclusion

When referring to the Saint Petersburg Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication, the main organisational and didactic scheme and framework of the

institution’ activity (and their subsequent adjustment to the

requirements of contemporary reality) and their adjustment to the requirements

of the changing reality, were well undoubtedly already set in the 1820s, this

is the next decade that brings a number of solutions which has significantly

changed the scope and character of the teaching process of future tsarist transport

services members at a higher level.

In the main part, of course, it could have been combined with the

particular change in the administrative position of the head of Board of Roads

of Communication and Public Buildings, which this new position found Count

Toll, who, undoubtedly showed a deep interest in the research and teaching

activities of Saint Petersburg Institute. This was essentially important in the

event of relatively abrupt and multiple changes in the position of the director

of the Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication, which process

was undoubtedly observed in that period.

With a chronic shortage of full-time, adequately educated employees of

the transport administration in Nicholas I’s Russia, the Estonian German

at the Russian service, Count Toll[34] hardly tried to bring (with the positive effect of this idea) the

strictest restrictions on access to the teachings of the Saint Petersburg

Transport Academy, especially for people in the view of tsarist authorities

considered as unauthorised, unnecessary, or even undesirable individuals. In

order to achieve such a goal, such solutions were introduced; a) intra-Russian

legal acts, explicitly excluding certain categories of the population from this

already limited “privilege”, b) introducing of extremely strict

defined requirements regarding the obligation to provide all documentation seen

as a condition sine qua non just to get access to the qualification exam

itself, c) exclusion of foreigners/aliens from any possibility to enter the

Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication, located in Saint

Petersburg.

The positivity that can be observed in the didactic activity of the

Institute of the 1830s is the maintenance or even expansion, of the already broadly

defined curriculum, which as it is, should be presumed full, and therefore,

implemented at a high substantive level. This high level of overall education

seems to be also confirmed by most of the results of the final exams, which to

much surprise, saw the Polish group of students as obviously over-represented

(as can be clearly deduced from the available detailed data for 1836) among all

adepts, standing for ¼ of them.

Thus, we have several paradoxes described in this article in the

didactic activity of the Institute of Corps of Engineers of Roads of

Communication. These are; a) limiting general access to the learning process

taking place simultaneously with an increasing need to have appropriate staff

country-wide,b) as a result of the previous, maintaining or further developing

in practice of the system which may be seen as an all too elitist education

(which, of course, came together with keeping of an unusually high threshold of

knowledge at the entrance to the Academy, also while going through the final

exams at the end of the educational process), presently when the need for the

moment would rather indicate introducing of “more mass” transport

education, c) narrowing participation in the teaching at the Institute to the

“non-alien” group of students, while at the same time appearing

among the adepts of definite national overrepresentation of Polish element.

References

1.

Genealogisches

Handbuch der baltischen Ritterschaften. Tail Estland,

Band 1. 1930. Görlitz: Verlag fur Sippenforschung und Mappenfunde, G.U. Starte.

[In German: Genealogical Handbook of Baltic Knighthoods. Tail Estonia, Department of Genealogical Research and Portfolio

Findings, Görlitz: G.U.

Starte].

2.

Krusenstern

[de], Aleksandr Ivanovic. 1838. Rys

systemu, postępów i stanu oświecenia publicznego w Rossyi.

Ułożony z dokumentów urzędowych. Przełożony na

język polski przez Karola Jerzmanowskiego. Warszawa: S.

Olgerbrand. [In Polish: An outline of the system, progress and state of public enlightenment in

Russia. Composed from official documents. Translated into Polish by Karol

Jerzmanowski. Warsaw: S. Olgerbrand].

3.

Larionov

Aleksiej Mihailovic. 1910. Istoria

Instituta Inzenierov Putej Soobscenja Imperatora Aleksandra I-go za pervoje

stoletje jego sucestvovanja 1810-1910. Sankt Petersburg.

Tipografia Ju. N. Erlich. [In Russian: History

of the Institute of Engineers of Roads of Communication of Imperator Alexander

I for first one hundred years of its existence. Saint Petersburg: Printing

House of Ju. N. Erlich]

4.

Neoficjalnyj sajt Lokomotivnogo Depo Voronez - Kursk

bostocno-juznoj zeloezndodorogi. Available at:

http://vrn-6.ucoz.ru/index/istorija_formennoj_odezhdy_

zheleznodorozhnikov/0-68. [In Russian: Unofficial Site of the Depot of

South-East Voronez –Kursk Raiload].

5.

Okolski

Antoni. 1880. Wykład prawa administracyjnego oraz prawa administracyjnego

obowiązującego w Królestwie Polskiem. Warszawa: Redakcya

Biblioteki Umiejętności Prawnych. [In Polish: The Lecture of

Administrative Law and Polish Administrative Law in Force in the Kingdom of

Poland. Warsaw: Editorial Office of Library of Legal Utilities].

6.

Polnoje

Sobranje Zakonov Rossijskoj Imperii, Sobranje Vtoroje. 1830. Vol. 4, 1829, Tipografia Vtorogo

Otdelenja Sobstvennoj Jego Imperatorskogo Velicestva, Sankt Petersburg, 1830. [In

Russian: Full Digest of Laws of the

Russian Empire. Second Edition. Saint Petersburg: Printing House of Second

Division of His Imperial Majesty’s Chancery].

7.

Polnoje Sobranje Zakonov Rossijskoj

Imperii, Sobranje Vtoroje, Vol. 1834, Tipografja Vtorogo Otdelenja Sobstvennoj

Jego Imperatorskogo Velicestva, Sankt Petersburg, 1835. [In Russian: [In

Russian: Full Digest of Laws of the Russian Empire. Second Edition. Saint

Petersburg: Printing House of Second Division of His Imperial Majesty’s

Chancery].

8.

Programma

dlja ekzamena vospitannikov Instituta Korpusa Inzenierov Putej Soobscernja,

1824/ Programme pour l'examen des elèves de L'Institut du corps des

ingénieurs des voies de communication. Tipografia

Imperatorskoj Akademii Nauk, Sankt Peterburg 1824. [In Russian and French: Exam program for cadets of the Institute of

Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communications 1824. Saint Petersburg:

Printing House of the Imperial Academy of Sciences].

9.

Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta Urzędowa

Królestwa Polskiego, March 9/21,

1834, No. 18. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of

Kingdom of Poland. Saint Petersburg: J.E.

Przecławski].

10.

Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta Urzędowa

Królestwa Polskiego, April 6/18,

1834, No. 26. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of

Kingdom of Poland. Saint Petersburg: J.E.

Przecławski].

11.

Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta Urzędowa

Królestwa Polskiego, April 10/22,

1834, No. 27. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly.

Official Gazette of Kingdom of Poland. Saint

Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

12.

Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta Urzędowa

Królestwa Polskiego, May 11/25,

1834, No. 35. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of

Kingdom of Poland. Saint Petersburg: J.E.

Przecławski].

13.

Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta Urzędowa

Królestwa Polskiego, March 8/20,

1835, No. 19. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of

Kingdom of Poland. Saint Petersburg: J.E.

Przecławski].

14.

Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta Urzędowa

Królestwa Polskiego, March 15/27,

1835, No. 21. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of

Kingdom of Poland. Saint Petersburg: J.E.

Przecławski].

15.

Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta Urzędowa

Królestwa Polskiego, June 16/28,

1836, No. 45. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of

Kingdom of Poland. Saint Petersburg: J.E.

Przecławski].

16.

Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta Urzędowa

Królestwa Polskiego, December

15/27, 1836, No. 97. Sankt Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of

Kingdom of Poland. Saint Petersburg: J.E.

Przecławski].

17.

Tygodnik Petersburski. Gazeta Urzędowa

Królestwa Polskiego, May 14/26,

1837, No 37. Sankt

Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski. [In Polish: Petersburg Weekly. Official Gazette of Kingdom of Poland. Saint Petersburg: J.E. Przecławski].

18.

Zitkov

Sergej Mihailovic. 1899. Institut Inzenierov

Putej Soobscenia Imperatora Aleksandra I, Istoriceskij ocerk. Sankt

Petersburg: Tipografia Ministerstva Putej Soobscenia. [In Russian: Institute of Engineers of Roads of

Communication of Imperator Alexander I. A Historical sketch. Saint

Petersburg: Printing House of Ministry of Roads of Communication].

19.

Sokolovskij Evgenii Matveevic. 1859. Piatidiesatiletje Instituta i Korpusa

Inzenierov Putej Soobscenja, Istoriceskij ocerk. Sankt Petersburg:

Tipografja Torgovago Doma S. Strugovscikova, G. Pohitonova, N. Vodova i Ko. [In

Russian: Fifty years of the Institute of

Corps of Engineers of Roads of Communication. A historical sketch. Saint

Petersburg: Printing House of Commercial House S. Strugovscikov, G. Pohitonov,

N. Vodov and Co.].

20. Żywicki Jerzy. 2010. Kształcenie kadr dla

potrzeb Królestwa Polskiego w zakresie architektury, budownictwa oraz

inżynierii cywilnej. Lublin:

Annales Universitates Mariae Curie Skłodowska, Vol VIII, 1. [In Polish: Education of Personnel for the Needs of the

Kingdom of Poland in Architecture, Construction, and Civil Engineering].

Received 12.10.2018; accepted in revised form 15.01.2019

![]()

Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License