Article citation information:

Villarreal Chávez, D.B., Kurek, A., Sierpiński,

G., Jużyniec, J., Kielc, B. Review and comparison of traffic calming solutions:

Mexico City and Katowice. Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2017, 96, 185-195. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2017.96.17.

Delia

Berenice VILLARREAL CHÁVEZ[1], Agata KUREK[2], Grzegorz SIERPIŃSKI[3], Jakub JUŻYNIEC[4], Bartosz KIELC[5]

REVIEW AND COMPARISON OF TRAFFIC CALMING

SOLUTIONS: MEXICO CITY AND KATOWICE

Abstract.

The article addresses solutions implemented in two cities, namely, Mexico City

and Katowice, with the aim of improving road traffic safety. Despite the

distance of more than 10,000 km separating the two cities, a comparison revealed

many similar solutions having been implemented in both of them. This

comparative case study is complemented with a collation of statistics

pertaining to accidents, fatalities and injured persons as reported in the

period 2012-2015.

Keywords:

traffic calming; traffic engineering; road safety

1. INTRODUCTION

Poland is currently still ranked above other

countries in respect of poor road traffic safety. The group of unprotected

traffic participants, namely pedestrians, typically accounts for one third of

all road traffic accident fatalities. In Silesia Province, 257 persons were

killed in road traffic accidents in 2016, including as many as 99 pedestrians.

The World Health Organization positions Mexico in seventh place for fatal

traffic accidents in the world, with Mexico City being the country’s most

significant contributor to the number of incidents in this respect.

In both places (Katowice and Mexico City), one

can observe a significant increase in the number of solutions implemented over

recent years in terms of traffic calming. The primary objectives of these

efforts include reducing vehicle speed and separating transit from commuter

traffic, thus minimizing the negative effects of road traffic, which translate

into specific numbers of fatal accidents and injuries. Speed exerts a major

impact on traffic safety, as it affects both the number of accidents and their

severity [10]. Drivers maintaining a safe running speed in a manner that

matches road conditions (visibility, curves, intersections, pedestrian

crossings and public transport stops, pavement roughness and levelness, road

surroundings, weather conditions), as well as traffic conditions (traffic

intensity, other vehicles’ running speed, overtaking conditions, presence of

pedestrians at road shoulders), is a factor that favours safe traffic. As

running speed rises, the degree of road traffic accident severity increases, as

does the hazard for traffic participants, whereas the possibilities of avoiding

collisions dwindle [1, 2, 13, 14, 19, 20].

In this article, activities aimed at traffic

calming in Mexico City and Katowice are compared. In the next section, a

collation of road traffic safety statistics is presented. Both the aspects

analysed confirm that the situation has been improving.

2. TRAFFIC CALMING: A

COMPARATIVE CASE STUDY ON MEXICO CITY AND KATOWICE

Car traffic in city centres is an

issue that provokes much controversy. All activities aimed at the

reorganization of city centre traffic are usually widely approved by one or

several groups of inhabitants, while raising objections in others. It is for

this very reason that undertaking bold efforts, such as establishing traffic

calming zones or limiting access to selected streets at the heart of the city,

has often been extremely difficult. There are also cases when one can place

such problems as urban traffic flow or safety of pedestrians and cyclists into

one basket, and the private interests of persons commuting into city centres by

car (and using a car to move around within the centre) into another, as the

latter are often unaware of the benefits that urban traffic calming or

switching to alternative means of transport may bring.

One may refer to numerous premises

and conditions behind the implementation of the traffic calming concept, such

as the following (among others [15, 16, 17, 18]):

• Arterial roads being overflown

with cars

• Policies that favour commuting

by car

• Pollution and noise increases

due to car traffic

• Degradation of urban space due

to car traffic and parking

• Declining road traffic safety

and growing threats for pedestrians and cyclists due to excessive running speed

The authors of the article have

decided to address the traffic calming problem using examples from two

significantly different cities, namely, Mexico City and Katowice. The

population of Mexico City exceeds 8.9 million people [12], while Katowice is

inhabited by around 0.3 million people (the total population of Silesia

Province is less than 4.6 million) [7].

Examples of the solutions applied in

Mexico City are illustrated in Fig. 1.

|

a) Speed radars |

b) Video recorders |

|

c) Breathalyser operations |

d) Speed bumps |

|

e) Secure lanes for truck freight |

f) Night operations |

Fig. 1. Comparison of traffic

calming solutions implemented in Mexico City

(source: based on [8])

The most fundamental solutions

include speed radars (58 pieces distributed all over the city) and speed bumps.

Various analyses imply that speed bumps are the most efficient traffic calming

tool. The most commonly used bumps are 3.6 x 6.6 m in length. Under Polish

conditions, speed bumps reduce the traffic stream speed by 25% compared with

the obligatory speed limit [12]. Frequent sobriety checking is also an

efficient means to improve safety (Fig. 1c). Inhabitants may already be familiar

with speed limit regulations, speed radars and speed bumps, but the latest

implementation for road safety in Mexico is the use of video recording devices

(Fig. 1b). These video recorders (currently 40 devices installed all over

the city) feature cameras installed at strategic points of the city, designed

to record the moments when the driver does not respect traffic lights,

forbidden turns, pedestrian crossings or bike tracks. These cameras also record

situations when drivers are not wearing their seatbelts properly or when they

are using mobile phones while driving. Whenever the camera detects one of these

infringements, the system automatically sends a ticket to the car owner.

In order to ensure safety for

people, as well as for truck freight, a plan for night routes has been

established for freight circulation, each of which is monitored. The Mexican

authorities have defined specific routes for cargo vehicles, as well as driving

hours, on access-controlled high-speed roads with a maximum speed of 60 km/h.

The least common traffic calming

solution used in Mexico City is referred to as night operations (Fig.

1f), which have also contributed to a significant reduction in the number of

night incidents. Every night, on average, there are 73 such operations

conducted all over the city, whose main goal is to educate drivers by placing a

line of police patrol vehicles at the front of a vehicle traffic column,

circulated at a regulated speed on controlled access roads. This has led to a

reduction of 13% in the number of car accidents during the night shift (from

22:00 to 06:00).

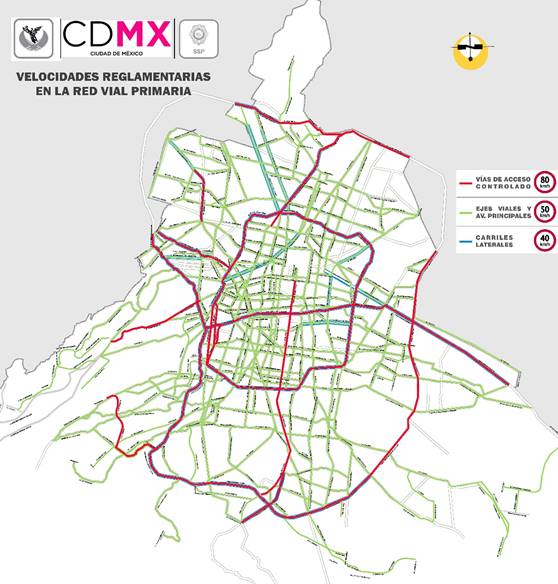

The driving speed limitations

introduced in Mexico City range between 80 and 10 km/h, depending on the

specific location or the speed limit zone. These speed limitations have been

collated in Table 1. In most streets in the city, one can drive a car at 50

km/h, with the exception of several trunk roads (these being subject to intense

speed monitoring), where the permissible speed is 80 km/h (Fig. 2)

Tab.

1

Comparison of speed limit zones introduced in

Mexico City

|

Speed limit |

Sector |

|

10 km/h |

In car parks and on

pedestrian paths in which access to vehicles is allowed |

|

20 km/h |

In scholar zones,

hospitals, nursing homes, shelters and homes |

|

30 km/h |

In quiet transit zones |

|

40 km/h |

On secondary roads

including the sides of controlled access roads |

|

50 km/h |

Circulation on primary

roads |

|

80 km/h |

Central lanes of

controlled access roads |

(source:

based on [8])

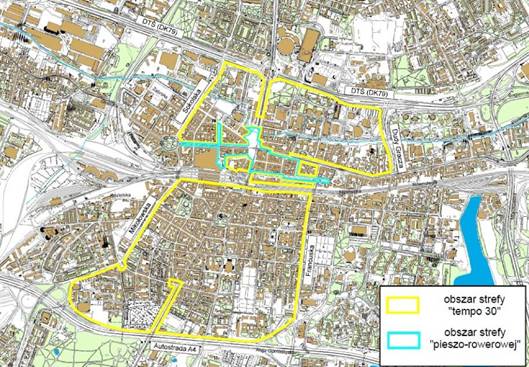

Being the capital city of Silesia

Province, Katowice features a very dense road network. On account of the

necessity to improve pedestrian safety and the need for a modal split

transformation in favour of alternative solutions to the use of passenger cars,

a special traffic calming zone corresponding to the city centre was introduced

in 2015 (Fig. 3). Entrance to the zone, referred to as “Tempo 30”, has been

distinctively marked with vertical and horizontal signs (Fig. 4a-b). The most

popular traffic calming facilities used there are the speed humps (speed

cushions) installed at the zone borders, forcing drivers to reduce their speed

considerably. The chosen locations where these measures have been used are

situated near to centres of culture, public offices or schools (Fig. 5a). Other

characteristic elements of the solutions implemented there are raised

pedestrian crossings, as well as road pavements, which have been redeveloped

using paving stone (Fig. 5b). One can also encounter entire intersections,

which have been raised and stone paved (Fig. 5c). Due to uneven pavement

surface, drivers reduce their driving speed in order to avoid damaging their

car. (Intentional) chicanes represent another traffic calming measure applied

in Katowice. In the case shown in Fig. 4f, the chicanes were developed by

alternating locations of parking spaces (on the left-hand and the right-hand

side, alternately), forcing drivers to dynamically change the driving track and

reduce speed.

Fig. 2. Map of Mexico City streets

subject to speed limitations

(excluding zones with speed limits

below 40 km/h) [8]

Fig. 3. Map of Katowice with the “Tempo 30”

traffic calming zone marked (yellow colour delimits the “Tempo 30” zone, while

blue marks the “walking and biking only” zone)

(source: [6])

|

a) Szkolna

Street, Katowice |

b) Jagiellońska Street, Katowice |

Fig. 4. Marking at the beginning of the “Tempo

30” zone in Katowice (source: own research)

|

a) Traffic calming elements known as speed cushions (Andrzeja Street,

Katowice) |

b) Marking at the beginning of the “Tempo 30” zone (Jagiellońska Street,

Katowice) |

|

c) Raised intersection (Sienkiewicza and

Powstańców Streets, Katowice) |

d) Alternating parking spaces (Plebiscytowa Street, Katowice) |

Fig. 5. Comparison of selected

traffic calming solutions implemented in Katowice

(source: own research)

Within the traffic calming zone of

downtown Katowice, a walking and biking only zone has also been sectioned off

(marked in blue on Fig. 3), which covers streets where automotive vehicles are

forbidden to enter (including Mariacka, Staromiejska, 3-go Maja, Stawowa and

Rynek Streets). That said, this zone has not eliminated another element

threatening pedestrians, namely, trams running on lines that intersect to a

considerable extent in the main square area (Rynek). In order to reduce

accident hazard exposure, an innovative solution has been applied, i.e., long

colour-changing lamps embedded in the pavement. As a default, they emit green

light when there is no tram approaching, but, when one is incoming, their

illumination changes to red. Owing to this solution, even when paying no

special attention to the surrounding, pedestrians will realize the tram’s

proximity. An example illustrating the concept is provided in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Lights warning pedestrians of an

incoming tram (source: own research)

3. REVIEW OF ACCIDENT STATISTICS FOR 2012-2015

A review of the Mexico City accident statistics (Table 2) for the last

five years implies that the situation has improved significantly. The number of

traffic accidents and fatalities has decreased considerably in recent years in

Mexico City. From 2011 to 2015, the number of persons injured dropped by nearly

49%, whereas the number of fatalities dropped by more than 38%. A considerable

quantitative drop, i.e., by 48%, was also observed in traffic accident figures.

The decrease in the number of accidents involving pedestrians is yet another

positive fact worth mentioning. This is due to the safety and public awareness

programmes that have recently been implemented in different parts of the

capital city.

Tab.

2

Mexico City accident statistics

|

Year |

Fatal

traffic accidents (deaths)

|

Non-fatal

traffic accidents (injured) |

Persons killed in traffic accidents |

Persons injured in traffic accidents |

Accidents involving pedestrians |

|

2012 |

315 |

4,221 |

343 |

5,673 |

1,248 |

|

2013 |

342 |

3,548 |

370 |

4,801 |

1,112 |

|

2014 |

291 |

2,822 |

312 |

3,799 |

1,017 |

|

2015 |

200 |

2,147 |

210 |

2,899 |

748 |

(Source: own research based on [3])

With regard to Katowice, the number

of fatalities dropped by 40% in the corresponding period (Table 3). However,

the decrease in the number of traffic accidents (by only as much as 7%) and

persons injured (8%) does not imply any major improvement in this respect.

Therefore, the implementation of the “Tempo 30” zone in 2015 should be regarded

as well grounded, since a more significant improvement was achieved in a

similar period, compared to the entire

province, which translated into nearly 19% fewer accidents and 20% fewer

injured persons (Table 4).

Tab. 3

Katowice accident statistics

|

Year |

Total traffic accidents (deaths and injured) |

Persons killed in traffic accidents |

Persons injured in traffic accidents |

Pedestrians killed in traffic accidents |

Pedestrians injured in traffic accidents |

|

2012 |

301 |

20 |

338 |

10 |

113 |

|

2013 |

303 |

21 |

352 |

14 |

94 |

|

2014 |

276 |

14 |

322 |

9 |

158 |

|

2015 |

280 |

12 |

311 |

7 |

98 |

(Source: own research based on [5, 10])

Tab.

4

Silesia Province accident statistics

|

Year |

Total traffic accidents (deaths and injured) |

Persons killed in traffic accidents |

Persons injured in traffic accidents |

|

2012 |

4,675 |

336 |

5707 |

|

2013 |

4,529 |

267 |

5506 |

|

2014 |

4,360 |

249 |

5324 |

|

2015 |

3,792 |

255 |

4584 |

(Source: own research based on

[4])

The initial period when the “Tempo 30” zone was functioning triggered

an improvement in road traffic safety across the zone area. The total number of

accidents in the zone dropped by 41% in 2016 (compared to 2014, i.e., before

the zone concept implementation), while the number of injured persons declined

by 32%. A similar comparison for accidents involving pedestrians and cyclists

is provided in Fig. 7. One can also notice a clear improvement in safety within

the zone in this respect.

Fig. 7. Comparison of statistics for

accidents involving pedestrians and cyclists that took place in the “Tempo 30”

zone in Katowice in 2014 and 2016

(source: own research based on [4])

4. CONCLUSIONS

The traffic calming

methods discussed in the article are mainly related to infrastructural

solutions. In both cities analysed in the paper, physical obstacles forcing

drivers to reduce driving speed and speed limit zones were deployed. As confirmed

by the analysis, both the number of accidents and the number of persons killed

and injured declined (the analysis covered the period 2012-2015), although the

improvement thus achieved was more evident in Mexico City. The fact that should

be emphasized is that fatality figures increased in 2013 in both cities. Other

speed limiting methods, which also deserve to be highlighted, include the night

operations introduced in Mexico City, since this solution prevents driving

faster than the speed limit set by police vehicles. This method has not been

applied in Poland.

References

1.

Bohatkiewicz

Janusz , ed. 2008. Zasady Spokajania

Ruchu na Drogach za Pomocą Fizycznych Środków Technicznych. [In Polish: Principles of Calming Traffic on Roads Using

Physical Technical Means.] Cracow. e-Book.

2.

Gaca

Stanisław, Wojciech Suchorzewski, Marian Tracz. 2008. Inżynieria Ruchu Drogowego. Teoria i Praktyka. [In Polish: Traffic

Engineering. Theory and Practice.] Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Komunikacji i

Łączności.

3.

INEGI. “Statistics

of traffic accidents in urban and suburban areas.” Available at:

http://www.inegi.org.mx/.

4.

Katowice City

Hall. “Data about ‘Tempo 30’ area” (not published).

5.

Katowice City

Hall, Faculty of Transport. 2015. Bieżąca

Analiza Wypadkowości na Sieci Drogowej Miasta (Porównanie za Lata 2010-2014).

[In English: Current

Accident Analysis on the City Road Network (Comparison for 2010-2014).]

6.

Katowice City

Hall. “Homepage.” Available at: https://www.katowice.eu/.

7.

Katowice

Statistical Office. “Regional statistics.” Available at:

http://katowice.stat.gov.pl/en/.

8.

Secretaría de

Seguridad Pública, CDMX 2017. Available at:

http://www.ssp.df.gob.mx/reglamentodetransito/.

9.

Szczuraszek

Tomasz, ed. 2005. Bezpieczeństwo Ruchu

Miejskiego. [In Polish: Urban Traffic

Safety.] Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Komunikacji i Łączności.

10.

City Committee of

Police in Katowice. “Homepage.” Available at:

http://katowice.slaska.policja.gov.pl/.

11.

World Population

Review. Available at:

http://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/mexico-city-population/.

12.

Zalewski

Andrzej. 2013. “Środki uspokojenia ruchu i ich oddziaływanie na prędkość.” [In Polish: “Traffic

calming measures and their impact on the speed”.] In: Seminarium “Speed Management”.

Generalna Dyrekcja Dróg Krajowych i Autostrad, Warsaw 17-18 October 2013.

Available at:

http://materialy.wb.pb.edu.pl/marekmotylewicz/files/2016/03/Środki-uspokojenia-ruchu-i-ich-oddziaływanie-na-predkość.pdf.

13.

Czech Piotr. 2017. “Physically disabled pedestrians -

road users in terms of road accidents.” In: E. Macioszek, G. Sierpiński, ed.,

Contemporary challenges of transport systems and traffic engineering. Lecture Notes in Network Systems, Vol.

2: 157-165. Springer. ISSN: 2367-3370. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43985-3_14.

14.

Czech Piotr. 2017. “Underage pedestrian road users in

terms of road accidents.” In: G. Sierpiński, ed., Intelligent

Transport Systems and Travel Behaviour.

Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Vol. 505: 75-85. Springer.

ISSN: 2194-5357. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43991-4_4.

15.

Kinderyte-Poškiene

Jurgita, Sokolovskij Edgar. 2008. “Traffic control elements influence on

accidents, mobility and the environment.” Transport

23(1): 55-58. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3846/1648-4142.2008.23.55-58.

ISSN: 1648-4142.

16.

Tajudeen Abiola

Ogunniyi Salau, Adebayo Oludele Adeyefa, Sunday Ayoola Oke. 2004. “Vehicle

speed control using road bumps.” Transport

19(3): 130-136. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/16484142.2004.9637965.

ISSN: 1648-4142.

17.

Donald Deborah,

Aidan McGann. 2013. Reducing Speed: The

Relative Effectiveness of a Variety of Sign Types. Research Report ARR 246

(1995). ISBN: 0 86910 685 6.

18.

Pour Alirez Toran,

Sara Moridpour, Abbas Rajabifard, Richard Tay. 2017. “Spatial and temporal

distribution of pedestrian crashes in Melbourne metropolitan area.” Road &

Transport Research: A Journal of Australian and New Zealand Research and Practice 26(1): 4-20. ISSN: 1037-5783.

19.

Madhumita Paul,

Ghosh Indrajit. 2017. “A novel approach of safety assessment at uncontrolled intersections

using proximal safety indicators.” European

Transport/Transporti Europei 65: 1-14. ISSN 1825-3997.

20.

Schmidt Marie,

Stefan Voß. 2017. “Advanced systems in public transport.” Public Transport 9(1-2): 3-6. DOI:

http://doi.org/10.1007/s12469-017-0165-z. ISSN: 1866-749X.

Received 26.04.2017; accepted in revised form 29.07.2017

![]()

Scientific Journal of

Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License