Article citation information:

Mindur, M. Methodology for examining the links

between transport and the economy. Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2017, 96, 129-137. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2017.96.12.

Maciej MINDUR[1]

METHODOLOGY FOR EXAMINING THE

LINKS BETWEEN TRANSPORT AND THE ECONOMY

Summary.

This paper discusses the findings of studies on the relationship between the

world economy and transport, based on the polynomial curve in 1995-2015. The

socio-economic measures were reviewed, recognizing that GDP, although not

reflecting what is happening in the social sphere, is the best indicator of

economic growth, especially its dynamics. The results of the review show a high

convergence in the shaping of the polynomial curves representing GDP and total

transport, which is confirmed by the closeness of this relationship, as well

the relationship between economic development and transport. The coefficients

R2 of the variables studied are fully reliable, ranging from 0.9725 to 0.9954.

Keywords:

economy; transportation; socio-economic measures

1. INTRODUCTION

This paper analyses the development

of the world economy and its relationship to transport, which has secured its

needs in the period 1995-2015. The needs of the economy resulting from its

functioning and development determine the size and form of transport. The

importance of transport (its functions and links with other sectors of the

economy) to the development of the economy, as well as the interrelationships

and interdependencies between the economy and transport, is also examined.

The study considers the economies of

the most developed countries, which have been the largest economies for

decades, the world’s largest GDP, and the trends in the contemporary world,

namely, the US, Japan and the EU-28. There are also two countries with enormous

potential, the largest area, significant natural and military resources, which

have been rapidly developing in recent years, namely, Russia and China (the

world’s most populous country, developing continuously for more than 30 years,

according to some reports, contributing more to global GDP than Japan).

The paper also considers Poland,

whose economy (in terms of size) cannot be compared with any of the economies

of the countries in question. Therefore, the analysis of the economic situation

was not compared in terms of macroeconomic size, but to the development of

economic processes. The study uses polynomial curves.

2. GDP: THE PRIMARY MEASURE OF ECONOMIC

RESEARCH

Analysts comparing the

socio-economic situation have, at their disposal, many measures of economic

development. The most prevalent of these is GDP, a measure of production

generated by manufacturing factors located in the territory of a country,

regardless of who owns it [1.]

The GDP of a given country

determines its share in global GDP. This measure does not take into account the

potential of individual countries; it would be difficult to assume that the

share of the US, a resource-rich country with 300 million inhabitants, would be

the same as the 500,000 inhabitants of Luxembourg (which equates to the area of

a Polish voivodeship).

Against this background, GDP per

capita is used more frequently, whereby

the GDP of the country is divided by the number of inhabitants (in the

example of GDP per capita in Luxembourg, it is USD 70,000, while, in the US, it

is USD 45,000).

The GDP measure, although commonly

used, is often criticized. First of all, it emphasizes that it is a determinant

of economic growth (especially its dynamics, i.e., the percentage growth of GDP

against the previous year), but it does not reflect what is happening in the

social sphere (mainly regarding the issue of GDP redistribution). Nevertheless,

it is often a component of other aggregates, as is the case with the Human

Development Index (HDI).

3. OTHER MEASURES FOR TESTING SOCIAL AND

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

In 1990, while looking for a measure

that would be more reliable than GDP in reflecting the social situation, the

Pakistani economist Mahbud ub Haqa created a new (previously mentioned)

aggregate, the HDI. This unit of measurement consists of three elements (two of

which are related to the social sphere, with the third intended to reflect the

socio-economic situation):

-

Education,

i.e., the ratio of enrolment

-

Health,

which is measured by life expectancy

-

Development,

which is expressed in GDP per capita according to purchasing power parity

The state of health measured by the

average citizen’s lifespan is, however, a measure to be discussed. Life

expectancy depends not only on the availability and quality of medical services

in a given country, but also on cultural values and climatic conditions; e.g.,

a long-term lack of sunshine behind the polar circle increases levels of

depression (especially among Europeans), which frequently (e.g., in Sweden)

lead to an increase in the number of suicides.

Another factor that affects health

and longevity is diet. It is well known that, for example, rich in meat and

fats, the Inuit diet is unhealthy and does not contribute to prolonging one’s

life, as opposed to the Mediterranean diet, which is considered to be much

healthier, reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Cultural habits, such as the

tendency of Nordic nations to participate in active forms of spending time

together and participating in sport, are also influenced by life expectancy, in

contrast to, for example, the US (especially Texas), whose citizens are fond of

‘gluttony’ and are known for disliking physical activities. It is difficult to

assume that US medicine is at a lower level than in Sweden (although, in the

latter country, it is more accessible to the majority of the population). This

does not change the fact that life expectancy is the result of cultural habits,

systems of values and climate, as well as the level of medical support in a

given country.

For the past few years, Norway has

been leading the HDI rankings, followed by Iceland, Switzerland, Canada,

Australia, Sweden, the Netherlands, Japan, France and, increasingly, Ireland.

Poor countries, such as Mali, Sierra Leone, Afghanistan and Niger, are in the

lowest positions.

The HDI is a measure used by

analysts working for the UN, along with the Human Poverty Index (HPI). The HPI

is divided into two types of measurement: HPI I and HPI II.

HPI I consists of the following:

-

Probability

of death before the age of 40

-

Degree

of illiteracy

-

No

access to running water

-

Children

being underweight

HPI II takes into account the

following:

-

Probability

of death before the age of 60

-

Long-term

unemployment

-

Degree

of illiteracy

-

Percentage

of the population with an income below 50% of the average income

Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands,

Finland, Denmark, Germany, Switzerland, Canada, Luxembourg and Austria are

among the countries with the lowest poverty levels.

Economic politicians, while

analysing social issues, focus primarily on income ranges. Their analysis

methods include a decile method, i.e., comparing 10% of the worst- and

best-located societies, or the quintal method, which compares the 25% best and

worst earners. Another way to investigate income scales is to use the so-called

Gini factor.

In recent times, various measures

have been popularized, which were not previously known in the theory of

economics, and are now more and more common in academic discussion forums.

These include the Index of Economic Freedom, where countries are classified

into one of four groups, on a scale of 1 to 5:

-

In

the first, from 1 to 1.9, there are those whose economies are considered free

(it is interesting to note that this group includes both countries whose

economies have long been considered liberal, e.g., the US, the UK or Hong Kong

, countries such as Denmark and Sweden, which have, for decades, been promoting

a model of a caring state with a large share of the public sector).

-

In

the second group, from 2 to 2.9, there are countries with “rather free”

economies (Poland is included in this group).

-

The

third group comprises countries between 3 and 3.9, whose economies are viewed

as “less liberal” rather than “free” (China and Russia are included here, among

others).

-

The

fourth group, from 4 to 5, comprises countries whose economies are considered

repressed [2].

This indicator is calculated as an

arithmetic mean after analysing several test areas. These are:

-

Trade

-

Tax

arrangements

-

The

extent of government intervention in the economy

-

The

monetary system

-

The

capital flow and foreign investments

-

Finance

and banking

-

Entrepreneurship

-

Property

rights

-

Honesty,

transparency and corruption

-

Labour

market

All the above-mentioned areas of

activity are analysed and evaluated. However, this factor raises much emotion.

First of all, great controversy is prompted when making comparisons between

countries that fall into each of the groups. For example, how it is possible to

explain the location of Italy in 67th place, between Uganda and Nicaragua, and

behind Oman, Belize and Kuwait, while the classification of France’s economic

freedoms are on a par with Jamaica? Meanwhile, why is Poland in 94th place,

between Senegal and Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan and the Cape Verde Islands? What

reasonable rationale is behind the placement of China and Russia in places 126

and 127, respectively, after Lesotho and Yemen, and Ukraine after Niger? Or the

classification of Vietnam, which has enjoyed rapid economic development in the

last 30 years, being on a par with the Central African Republic, which is

characterized by the stagnation? What about Iran, which is eighth from the end

[3]?

Secondly, this situation is also

questionable given that these analyses and evaluations are carried out by the

Heritage Foundation, an organization that declares independence, despite being

sponsored by the US government [3].

Thirdly, this factor assumes that

“economic freedom” is an optimal economic model, which is not shared by all

economists. This system is also denied by some governments, especially by those

from Asian countries, who rely on planned development. While comparing the

dynamics of GDP in countries with different models of economic development, one

can observe that liberalization does not always lead to rapid economic growth.

There is another measure, which,

although not “researching” the economy in the strict sense of the word, is of

the utmost importance: the indicator of corruption perception. Corruption,

leading to the misallocation of funds or inappropriate planning of investments,

can impede economic growth or limit the inflow of foreign investment.

The definition of the above

indicator consists of examining, on a scale from 1 to 10, the extent to which

states are corrupt. The results are analysed by Transparency International,

which publishes annual reports systematizing states from the least to the most

corrupt. Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Iceland, New Zealand, the Netherlands

and Luxembourg have led on the list for several years now, but the Democratic

Republic of the Congo, Pakistan, Bolivia and Nigeria close the list. Poland’s

lowering position in this ranking may cause some anxiety, as well as the fact

that, year per year, the distance between Poland and not only the leading

countries but also others from the region is widening.

The perception of consumption

factor, in the same way as the previously described measures, also provokes a

great deal of emotion and is often questioned. The most problematic is the way

of measuring corruption, which is not a phenomenon that can be parameterized.

So, to a large extent, the ranking created by Transparency International is

subjective.

As mentioned earlier, GDP, albeit a

commonly used measure, is also often criticized because it does not reflect

what is happening in the social sphere. Despite this criticism, it is

undoubtedly the best indicator of economic growth (and especially its

dynamics), which is why this indicator is used in this paper.

4. SHAPING OF GDP IN SELECTED COUNTRIES IN

1995-2015

GDP is a measure of production

generated by manufacturing factors located on the territory of a country,

regardless of who owns its.

-

The

GDP of a given country determines its share in global GDP (it does not take

into account the country’s potential)

-

GDP

per capita is more commonly used, i.e., GDP per one person

-

The

GDP measure is a determinant of economic growth (especially its dynamics), but

it does not show what is happening in the social sphere

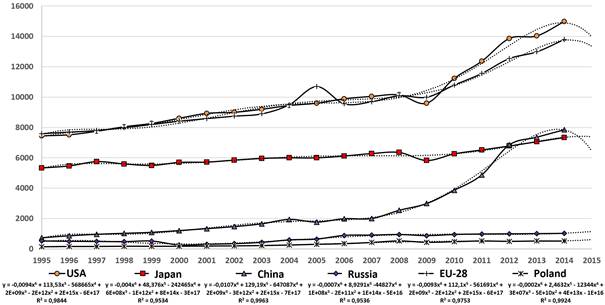

The analysis of GDP polynomial

curves in the studied countries and the EU-28 (Fig. 1) allows the following

conclusions to be drawn:

-

GDP

has not systematically increased in every country surveyed between 1995 and

2015

-

The

US has the highest GDP throughout the period under consideration.

-

Despite

the fact that GDP growth in the US in the early years has been at an average

level of around 3%, its growth has been much higher in recent years. Despite

its high (at that time) value at the beginning of the analysed period (1995),

the overall size of the increase was very large, which explains why the US

economy was (and is) the largest in the world.

-

The

second largest economy in the world is the EU-28 economy, mainly due to the

strong economies of Germany, France, the UK and Italy (these countries are

among the largest exporters).

-

The

third place in terms of GDP until 2011 was occupied by Japan, whose growth was

(and continues to be) systematic, stable and at a high level.

-

China,

whose rapid GDP growth since 2007 has resulted in its move into third position

in 2012 (ahead of Japan); the country is one of the world’s largest exporters.

-

Russia

and Poland are at the lowest level.

-

Although

the value of GDP for Poland was the lowest, we can observe constant growth until

2015.

The analysed countries produce more

than 70% of global GDP in the world, meaning that their economies have a

decisive influence on directions and trends in world production.

5. THE CARRIAGE OF GOODS IN SELECTED

COUNTRIES

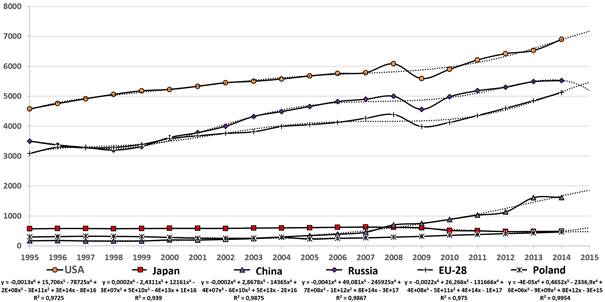

The shape of the polynomial curve

representing the volume of transport work performed in the most developed

countries of the world and in the EU (Fig. 2) shows a relatively close

relationship with their economic development (measured by GDP). The diversified

economic development and the nature of production is reflected in the volume of

freight movements (in ton/km):

-

The

US, as with the size of GDP, is at the highest level in the world. It should be

emphasized that, in general terms, the dominant role played in the period 1995-2015

was by the US railway.

-

Transport

activity in Russia has been very high, due to the high volume of extraction and

export of raw materials (fuel, gas).

-

Between

1995 and 2007, the EU-28 was characterized by steady growth; since 2009,

however, there has been considerable dynamics (it is important to mention here

that road transport is essential).

-

In

Japan, the carriage of goods was stable, but there has been a decline in recent

years.

-

The

polynomial curve showing the traffic in China points to a large increase, as

evidenced by the dynamic development of the Chinese economy.

-

In

Poland, the trend of the polynomial curve is at the same level, which could

mean that the development of modern technologies in production has resulted in

less commitment towards transport.

Fig. 1. Shaping of GDP in the selected world

economies (in constant prices in USD)

Fig. 2. Shaping of the total

carriages of selected countries (in billion tons/km)

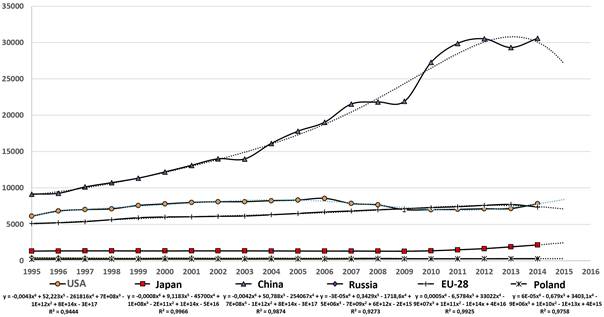

Fig. 3. Shaping of passenger

carriages in total for selected countries (in billion passengers/km)

6. SHAPING OF PASSENGER CARRIAGES (IN BILLION

PASSENGERS/KM) IN SELECTED COUNTRIES BETWEEN 1995 AND 2015

On the basis of studies on the

development of passenger transport, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

The

most dynamic, and at the highest level, are general passenger services in

China, which indicates a very high growth of the mobility of its society.

-

In

second place in the period being studied, with a slight upward trend, albeit

decreasing in the last few years, was the US (it can be emphasized that

individual transport in the US is the most developed in the world).

-

In

next place, with a stable and steady upward trend, are general passenger

services in the EU (here we also note a high growth of individual transport).

-

In

Japan, passenger services have remained at a constant and very even level,

which may prove that public transport vehicles in this country have the

capacity to satisfy needs in this area.

-

The

development of passenger services in Russia and Poland remains at a steady low

level.

The growth of passenger transport

(Fig. 3) in China and the EU-28 indicates an increase in the mobility of their

societies. The growth of passenger transport makes it possible to move freely,

which offers the possibility of the following [4]:

-

Wide

choice of workplaces

-

Continuing

and completing education at various levels

-

Greater

choice of consumer goods

-

Freedom

of choice regarding place of residence

Mobility, ensuring the free movement

of people and goods, also makes it possible to use them optimally, which is one

of the conditions for economic growth.

In the case of China, such a dynamic

growth of passenger transport was also undoubtedly influenced by the population

level of this country.

The shape of the polynomial curve

representing passenger carriage in Japan in 1995-2015 shows that public

transport in this country has already reached a level corresponding to its

population.

The steady level of passenger

traffic in Russia and Poland shows that both countries provide a stable level

of public transport, while doing little to develop it.

7. SUMMARY

Between 1995 and 2015, dynamic GDP

growth has been observable (from a high baseline) in the US and the EU-28.

Equally dynamic (from a much lower base level) has been the GDP growth in

China. The levelled upward trend (from a fairly high level) over the period

considered can be observed for GDP in Japan. Moderate growth trends (from very

low baseline levels) have been observed for GDP in Russia and Poland (Fig. 1).

The analysis of total cargo

movements for the stated time horizon of selected countries based on the

polynomial curve (Fig. 2) shows significant convergence in their formation in

the US, Russia and the EU-28. In all three cases, with a fairly similar

(average) starting level in 1995-2008, transport shows a clear upward trend.

2009 experienced a decline, but, by 2015, there was dynamic growth. In China,

from a much lower starting level between 1995 and 2005, they are now on a level

playing field, with a clear upward trend

visible from 2005 to 2015. In Poland, transport throughout the analysed period

is running at a low level. In Japan, although at a slightly higher level than

in China and Poland, in a way equalized in terms of transport from 1995 to

2007, before seeing a fall from 2007 to 2015. The high convergence in the

shaping of the polynomial curves representing GDP and total transport merits

attention, given the close connection and dependence between economic

development and transport. The coefficients of compatibility of R2 of the

tested variables are reliable, ranging from 0.9725 to 0.9954.

References

1.

Nasiłowski

Mieczysław. 1996. System Rynkowy,

Podstawy Mikro- i Makroekonomii. [In Polish: Market System,

Fundamentals of Micro- and Macroeconomics.] Warsaw: Key Text.

2.

Kędzior

Zofia, Grażyna Musiał, Henryk Brandenburg, eds. 2006. Ekonomia. Kierunki Badań. [In Polish: Economy. Research Directions.] Katowice: Akademia Ekonomiczna w

Katowicach.

3.

Kołodko Grzegorz.

2008. Wędrujący Świat. [In Polish: Wandering World.] Warsaw: Pruszyński i

S-ka.

4.

Liberadzki

Bogusław, Leszek Mindur. 2007. Uwarunkowania

Rozwoju Systemu Transportowego Polski. [In Polish: Conditions of Development of the Polish Transport System.]

Warszawa-Radom: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Technologii Eksploatacji, Państwowy

Instytut Badawczy.

Received 22.04.2017; accepted in revised form 18.08.2017

![]()

Scientific Journal of Silesian

University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution 4.0 International License