Article citation information:

Żukiewicz, P., Domagała, K. Problems with transport policy in Kosovo

after 2008. Scientific Journal of

Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2017, 94,

249-256. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2017.94.22.

Przemysław ŻUKIEWICZ[1],

Katarzyna DOMAGAŁA[2]

PROBLEMS WITH TRANSPORT POLICY IN KOSOVO AFTER 2008

Summary. The

aim of this article is to present the main problems of public transportation in

Kosovo after 2008 when the province’s parliament announced the declaration of

independence. We focus on the plans and documents that were signed between 2008

and 2010 in an attempt to compare them with the real impact of investments made

in the last five years. We show how the conflict between Belgrade and Prishtina

has influenced public transportation and examine the prospects for

problem-solving in this sector. To do this, we employ a neo-institutional

approach to the document analysis as the main research method.

Keywords: transport policy, Kosovo, Serbia,

Western Balkans

1. INTRODUCTION

Kosovo is a disputed territory in South-eastern

Europe. The Kosovo Conflict is based on the fact that this area is inhabited by

Albanians and Serbs. Despite the fact that Kosovo Albanians (Kosovars) declared

it an independent state in February 2008, according to the Serbian Constitution

of 2006, this territory is still within the Republic of Serbia.

To analyse the consequences of this conflict,

one needs to appreciate Kosovo’s troubled history [1]. Currently, its population

amounts to 1,739,825[3]. The

largest ethnic group comprises Albanians (92.9% of the total population), while

7% of the population consists of ethnic and national minorities, 1.5% of which

are Serb [2]. Historically, it has been a part of the Serbian Kingdom. For

several centuries it was under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, after which it

belonged to the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Following World War

II, communist rule in Yugoslavia inaugurated 34 years of modus vivendi among Serbs and Albanians in Kosovo under the central

government [3]. Kosovo has a land area of 10,908 km2, which equates

to only 4.3% of the territory of former Yugoslavia; indeed, it was the poorest

area within communist Yugoslavia.

The described territory has been an

administrative region since 1946, known as the Autonomous Province of Kosovo

and Metohija. In 1989, in a referendum held throughout Serbia, the authorities

largely reduced the autonomy of Kosovo. At the end of 1990s, the conflict

between Kosovo Albanians and Serbs became a humanitarian problem and drew the

attention of the international community, such that, in March 1999, NATO

launched a range of air bombardments against Serbia [4]. Despite numerous

attempts to resolve the Serb-Albanian conflict, the situation in Kosovo

remained very tense. Prepared in 2007 by Martti Ahtisaari, the Comprehensive

Proposal for the Kosovo Status Settlement [5] was negatively received by the

Serbs, who were afraid of losing part of their territory. As such, in February

2008, Kosovo unilaterally proclaimed its independence from the Republic of

Serbia [6].

2. PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION IN KOSOVO

The transport sector in Kosovo

offers reasonable potential, but the region still suffers from the effects of

the last financial crisis. Furthermore, the state budget is based on external

measures, especially loans and EU funds, while the unemployment rate in Kosovo

is over 30% [7]. Kosovo is a member of the South East Europe Transport Observatory (SEETO), which is a

regional transport organization established by the Memorandum of Understanding

for the Development of the Core Regional Transport Network, which was signed in

2004 by representatives from the governments of Albania, Bosnia and

Herzegovina, Croatia, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro and

Serbia, as well as representatives of the UN Mission in Kosovo and the European

Commission. The aim of the SEETO is “to promote cooperation on the development

of the main and ancillary infrastructure on the multimodal Indicative Extension

of TEN-T Comprehensive Network to the Western Balkans and to enhance local

capacity for the implementation of investment programmes” [8].

Shortly after the announcement of Kosovo’s declaration of independence,

the European Commission and the Ministry of Transport and Communications of

Kosovo commissioned an action plan, whose main points were concerned with the

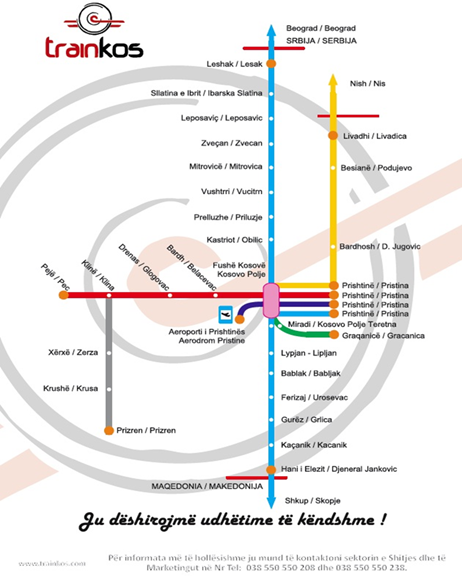

development of the railway network in Kosovo. In Table 1 and Figure 1, we

present all the new investments that were planned by the then government,

which were to lead to increasing numbers

of trains operating in the region.

Table 1. Overview of Kosovo’s railway projects in 2009 [9]

|

Project |

Type |

Value in EUR |

|

Fushë Kosovë- Hani i Elezit |

Double-track electrification 160

km/h |

145,089,000 |

|

Fushë Kosovë-Prishtinë |

Double-track electrification 160

km/h |

29,042,800 |

|

Fushë Kosovë-Leshak |

Single-track electrification 160

km/h |

105,233,900 |

|

Fushë Kosovë-Airport |

Single-track electrification 160

km/h |

16,209,600 |

|

Bardh-Pejë |

Single-track 160 km/h |

77,889,000 |

|

Klinë-Prizren |

Single-track 160 km/h |

58,121,400 |

|

Prishtinë-Podujevë |

Single-track 160 km/h |

39,710,200 |

|

Prizren-Vrbnica |

New line single-track 160 km/h |

13,391,100 |

|

Prishtinë Railway Station |

New intermodal station: rail

section |

10,000,000 |

|

Total cost |

|

494,687,000 |

Fig. 1. Overview of

Kosovo’s railway project in 2009 [10]

The plan

stipulated that transport should be organized in respect of the following

relationships:

·

Hani i Elezit-Fushë Kosovë - one train in both

directions every two hours (in total: 16 trains)

·

Hani i Elezit-Leshak - one train in both directions

every two hours (in total: 16 trains)

·

Prishtinë-Leshak - one train in both directions

every two hours (in total: 16 trains)

·

Hani i Elezit-Prishtinë - one train in both

directions every 1.3 hours (in total: 24 trains)

·

Prishtinë-Pejë - one train in both directions every

1.3 hours (in total: 24 trains)

·

Prishtinë-Prizren - one train in both directions

every 2.5 hours (in total: 12 trains)

·

Airport-Prishtinë - one train in both directions

every 1.5 hours (in total: 24 trains)

·

Prishtinë-Podujevë - one train in both directions

every 2.5 hours (in total: 12 trains)

·

Prishtinë-Vermice - one train in both directions

every 2.5 hours (in total: 12 trains)

Eight years

after the plan was established, there has been no progress regarding its

implementation. In 2016, passenger rail traffic was organized only for the

following domestic routes: Prishtinë-Pejë (two trains in both directions per

day) and Hani i Elezit-Fushë Kosovë (two trains in both directions per day).

There is also one international railway connection between the capital of

Kosovo and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (Prishtinë-Skopje). It

operates once every 24 hours [11]. The number of passengers in the period

2008-2016 declined steadily, which is not surprising in the context of a poor

offer.

The main

airport of Kosovo is now Pristina International Airport, which currently serves

19 destinations. This number is much lower if we only include state

destinations; currently, these are: Albania, Turkey, Croatia, Slovenia,

Hungary, Italy, France, Austria, Germany, Belgium, Sweden and Norway (in total:

12 countries). An important problem to be solved by the Kosovan Ministry of

Transportation and Communication is the lack of public transportation (any

buses and trains) between the airport and city centre. This explains why

passengers have to take a taxi or rent a car. Hence, there is still an obvious

need to establish a new train connection on the Airport-Prishtina route.

In recent

years, little has changed regarding road traffic in Kosovo as well [12, 26].

Table 2 shows the level of development on the road network in the region

between 2008 and 2015. For the last seven years, the number of routes has

increased by only 4.5%. This was mainly due to the construction of a strategic

section of the Ibrahim Rugova Motorway, which connects the capital of Kosovo

and the Kosovo-Albania border. While there are plans to extend this motorway to

the Serbian border in Merdare, at this moment, works are not continuing due to

political reasons.

Table 2. Roads in Kosovo between 2008 and

2015 [12]

|

|

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

Motorway |

0 |

0 |

0 |

38.0 |

60.4 |

78.0 |

78.0 |

78.0 |

|

National |

629.0 |

629.0 |

629.0 |

629.0 |

629.0 |

629.0 |

629.0 |

629.0 |

|

Regional |

1,294.7 |

1,294.7 |

1,294.7 |

1,294.7 |

1,294.7 |

1,294.7 |

1,294.7 |

1,305.0 |

|

TOTAL |

1,923.7 |

1,923.7 |

1,923.7 |

1,961.7 |

1,984.1 |

2,001.7 |

2,001.7 |

2,012.0 |

3. CONSEQUENCES OF THE CONFLICT FOR THE

EVERYDAY TRANSPORTATION

The number

of negative consequences of the conflict over Kosovo is significant. First of

all, the Republic of Kosovo has still not been recognized by all UN member

states (109 out of a total of 193 UN member states have recognized Kosovo’s

independence). While Kosovo I regarded as an institution of a “de facto state”

in international law [13], one can observe a huge divide between the de jure

status of land and the de facto reality on the ground [14]: in short, the

situation in Kosovo is still unstable. The widely understood “human damage of

the conflict” primarily relates to the young generation because of high

unemployment rates and the lack of proper access to education. Secondly,

systematic corruption in public procurement procedures and high rates of

poverty in society [15] result in frequent protests by both the Albanian and Serbian

communities.

Moreover,

Kosovo remains a lower-middle-income country. The unresolved status issue is a

main obstacle to attaining the country’s objectives of political integration

and socio-economic development [15]. Another important consequence caused by

the conflict and separation from Serbia is underdeveloped infrastructure and

the transport problem between two territories. It is worth mentioning that

infrastructure networks suffered from a decade of without maintenance, with 40%

out of almost 1,700 km of road found to be in “poor condition”. Railway lines

and many bridges are in a disrepair as the state budget is not able to afford

the necessary reconstruction and repair work.

There

is also political gridlock between Kosovo and Serbia, which affects the daily

life of citizens. Freedom of movement between these countries has been limited

since the war, as well as after Kosovo’s independence. It is thought that this

freedom is particularly restricted at the Kosovo-Serbia border because Kosovo’s

travel documents are not recognized by Serbian services [16]. One can

distinguish two approaches to this problem, along with two different

perspectives. On the one side, citizens of Kosovo are not able to travel to

Serbia, which means they are concerned not only about the obstacles to the free

movement of people, but also the free movement of goods, the difficulty in

accessing their private property and the lack of convenient border crossings.

Kosovars blame their authorities for failing to take into account their needs

[16]. Serbs also consider themselves as victims. Most of all, their family

relations have been hampered as Serbian authorities refuse to accept documents

issued by authorities in Pristina.

Although

Prishtina officials argue that Belgrade should be obliged to grant entry to

vehicles from Kosovo with licence plates labelled with RKS (Republic of

Kosovo), Serbian politician condemn the use of RKS licence plates, regarding

them as illegal and against the “status-neutral” policy [17]. A makeshift solution

of the problem is the possibility to drive in Serbia with temporary plates.

Unfortunately, it is not the only dispute concerning the recognition of travel

documents, as disagreement between vehicle insurance companies have occurred.

Owners of vehicles registered in Kosovo were obliged to pay around 120 euros to

enter Serbia and a daily fee of five euros for a 15-day stay. The

aforementioned fees included the use of temporary licence plates for Kosovo

drivers [17]. Drivers of cars registered in Serbia were compelled to pay about

20 euros to be able to drive in Kosovo for a week [18]. Moreover, mutual

non-recognition of vehicle insurance has been a key obstacle to cost-efficient

travel between the two countries.

Another

hotspot in the cross-border relations between Kosovo and Serbia is the

Mitrovica Bridge, which divides the city into a Serbian part and an Albanian

part. Members of both national groups do not go beyond their part of the city,

nor exceed the frontier, which has been informally established on the bridge

[19]. The main formal obstacle concerning the Mitrovica Bridge is the status of

former Yugoslav licence plates, given that they carry Kosovo City’s initials

“KM” (Kosovo Mitrovica); not surprisingly, the Serbian authorities do not

recognize these plates.

After

Kosovo declared independence in February 2008, it started issuing passport and

identification documents for the citizens of the Republic of Kosovo. Continuing

the Serbian policy of treating Kosovo as a part of its own territory, the Serbian

Government has not stopped issuing documents to residents in Kosovo. These

documents are available for Kosovo

inhabitants as proof of Serbian citizenship [20].

Another noteworthy issue is free movement in the case

of air travel, which also seems to be left up to chance. Formal requirements

for travel documents recognized at airports remain similar to those for road

traffic. Travellers with documents issued by the Government of Kosovo ought to

show their ID card and passport during check-in at the airport[4].

Likewise, travellers with document issued by the Government of Serbia are

obliged to have their ID card and passport [20]. Despite this, a study

conducted by the Big Deal Agency shows that the system is not foolproof. Kosovo

respondents reported that “they have been able to depart from and land in

Belgrade airport, though the process takes approximately an extra half an hour

because of paperwork” [21]. Moreover, uncomfortable situations occur from time

to time when Kosovo citizens are not allowed to board a plane to Belgrade. It

seems that airlines operating flights between the two countries are not

informed about the latest agreements [22].

4. CONCLUSION – PERSPECTIVES ON THE NORMALIZATION OF THE BELGRADE-PRISHTINA

RELATIONSHIP

Normalization

of the relations between Kosovo and Serbia became possible thanks to EU

commitment. One should know that Serbia already has candidate status to join

the EU, while Kosovo is seeking closer integration with Brussels. The

EU-facilitated dialogue began in March 2011 [20]. Within five years, under the

auspices of the EU institutions, parties were able to negotiate a number of

agreements that led to political and technical cooperation [23].

On 2

July 2011, Kosovo and Serbia agreed upon rules and standards concerning the

ability to travel. The Freedom of Movement Agreement [24] regulates issues

relating to personal documents, license plates and car insurance. Pursuant to

the terms of the agreement, residents of each country are able to travel freely

within the other’s territory. The requirement to purchase boundary insurance

should only be seen as an interim solution. Furthermore, parties agreed that

all car owners residing in Kosovo could use either RKS or KS vehicle license

plates, provided that the issue of KS plates would be reviewed by the parties

in the near future.

On 22 June 2013, the authorized entities responsible

for the vehicle insurance of each party, that is, the Association of Serbian

Insurers and the Kosovo Insurance Bureau, signed the Agreement on Insurance

[25]. The document states that “users of motor vehicles registered in one Party

who are in possession of a valid insurance for the territory of the other Party

may freely travel in that jurisdiction... In case the users do not present a

valid insurance, they will be obliged to contract mandatory border insurance”

[25]. Although the discussed agreements were warmly welcomed by the EU, the

dialogue needs to expand upon the issues of railway transport and air traffic

(while Serbia and Kosovo have agreed to establish flights between their capital

cities, due to political difficulties, the plan will be launched in 2017 at the

earliest).

References

1.

Malcolm Noel. 1999. Kosovo: A

Short History. New York, NY: Harper Perennial. ISBN: 978-0060977757. Judah

Tim. 2008. Kosovo. What Everyone Needs to

Know. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195373455.

2.

European Centre for Minority Issues Kosovo. Minority Communities in the 2011 Kosovo Census Results: Analysis and

Recommendations. Policy Brief from 18th December 2012. 2016.

Available at:

http://www.ecmikosovo.org/wp-content/Publications/Policy_briefs/2012-12_ECMI_Kosovo_Policy_Brief_-_Minority_Communities_in_the_2011_Kosovo_Census_Results_Analysis_and_Recommendations/eng.pdf.

3.

Wolff Stefan. “The Kosovo conflict”. 2016. Available at:

http://www.stefanwolff.com/files/kosovo.pdf.

4.

Jura Cristian. 2013. “Kosovo - history and actuality.” AGORA International Journal of Juridical

Sciences, Vol. 3: 78-84. ISSN 1843-570X.

5.

U.S. Department of State. “Summary of the Comprehensive Proposal for the

Kosovo Status Settlement”. 2016. Available at:

http://www.state.gov/p/eur/rls/fs/101244.htm.

6.

Assembly of the Republic of Kosovo. “Kosovo Declaration of Independence”.

2016. Available at: http://www.assembly-kosova.org/?cid=2,128,1635.

7.

Żukiewicz Przemysław. 2013. Deficyt

polityki społecznej w warunkach kryzysu gospodarczego. Zarys problematyki na

przykładzie państw Bałkanów Zachodnich [In Polish: Social Policy Gap

in Economic Crisis Circumstances. Cases from the Western Balkan Region]. Poznań:

Prodruk. ISBN: 978-83-64246-16-6.

8.

SEETO. “Welcome to SEETO”. 2016. Available at: http://www.seetoint.org/.

9.

SEETO. “Railway Transport in Republic of Kosovo. Action Plan and

Investment Plan. March 2009”. 2016. Available at:

http://www.seetoint.org/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2014/01/Kosovo_Railway-Action-Plan.pdf.

10.

Trainkos. “Harta

e rrjetit hekurudhor në të cilën operon Trainkos Sh.A.” 2016. Available at:

http://www.trainkos.com/sherbimet/transporti-i-udhetareve/harta/.

11.

Trainkos. “Orari i trenave”. 2016. Available at: http://www.trainkos.com/sherbimet/transporti-i-udhetareve/orari-i-trenave/.

12.

Kosovo Agency of Statistics. “Transport and Telecommunications

Statistics Q1 - 2016”. 2016. Available at:

https://ask.rks-gov.net/en/transport?download=1508:transport-and-telecommunications-statistics-q1-2016.

13.

Pegg Scott. “De facto states in the international system”. 2016.

Available at:

http://www.liu.xplorex.com/sites/liu/files/Publications/webwp21.pdf.

14.

Garrigues Juan. “De jure vs. de facto: a pyrrhic victory in Kosovo”. 2016. Available at:

http://fride.org/download/kosovo2.pdf.

15.

World Bank. “Kosovo”. 2016.

Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.NAHC/countries/XK?display=graph.

16.

Safeworld. “Drawing

boundaries in the Western Balkans: a people’s perspective report”. 2016. Available at: http://www.saferworld.org.uk/downloads/pubdocs/Drawing%20boundaries%20in%20the%20Western%20Balkans.pdf.

17.

Balkan Insight. “Kosovo, Serbia suspend cross-border car agreement”.

2016. Available at:

http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/kosovo-serbia-suspend-vehicle-agreement.

18.

Balkan Insight.

“Kosovo-Serbia car insurance deal starts”. 2016. Available at: http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/kosovo-serbia-cross-border-car-agreement-starts-today-08-11-2015.

19.

Balkan Insight.

“Serbia, Kosovo far apart on Mitrovica Bridge deal”. 2016. Available at: http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/serbia-kosovo-intepret-deal-on-mitrovica-bridge-differently.

20.

Hamilton Aubrey,

Jelena Šapić. “Dialogue-induced developments on the ground: analysis on

implementation of the EU-facilitated agreements on freedom of movement and

trade between Kosovo and Serbia”. 2016. Available at: https://dgap.org/sites/default/files/article_downloads/glps_kosovo_inter_serbia_dialogue-induced_developments.pdf.

21.

Big Deal Agency. Civic Oversight of the Kosovo-Serbia

Agreement Implementation Report. 2016. Available at: http://birn.eu.com/en/file/show/ENG-publikim-BIGDEAL-3-FINAL.pdf.

22.

Prishtina Insight.

“Up in the air: the patchy implementation of Kosovo-Serbia air travel deal”. 2016. Available at: http://prishtinainsight.com/air-patchy-implementation-kosovo-serbia-air-travel-deal/.

23.

Office for Kosovo and Metohija, Government of the Republic of Serbia. “Negotiation process with Pristina”. 2016.

Available at: http://kim.gov.rs/eng/pregovaracki-proces.php.

24.

Office for Kosovo

and Metohija, Government of the Republic of Serbia. “Freedom of Movement

Agreement”. 2016. Available at: http://kim.gov.rs/eng/p11.php.

25.

Office for Kosovo

and Metohija, Government of the Republic of Serbia. “Agreement on Insurance”. 2016. Available at: http://kim.gov.rs/eng/p14.php.

26.

Paddeu Daniela. 2016.

“How do you evaluate logistics and supply chain performance? A review of the

main methods and indicators”. European

Transport \ Trasporti Europei, Issue 61, Paper n 4: 1-16. ISSN: 1825-3997.

Received 03.11.2016;

accepted in revised form 29.12.2016

![]()

Scientific Journal of Silesian University of

Technology. Series Transport is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License