Article citation information:

Rutkowski, M. Water canal system in projects, activities and reports of

Polish authorities in the 1830s-1860s. Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2017, 94,

211-228. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2017.94.19.

Marek RUTKOWSKI[1]

WATER CANAL SYSTEM IN

PROJECTS, ACTIVITIES AND REPORTS OF POLISH AUTHORITIES IN THE 1830S-1860S

Summary. The

aim of this article is to present the endeavours undertaken in the 19th century

by diverse governing bodies to build or (rebuild) and eventually improve the

Polish water canal system. These activities concerned commissions from the

Second Council of State, the Administrative Council, the Third Council of State

and, inevitably, the Board of Land and Water Communications/Board of the 13th

District of Communications, among others. In addition, some of the general

state reports, especially those focusing on water transport issues, are

analysed in this article. All of the researched matters deal with the following

canals: Augustów, Windawa, Brudnów and Wisła-Narew.

Keywords:

water canal system, Kingdom of Poland, 19th century

1.

INTRODUCTION

The fall of the November Uprising of 1831

represented an obvious and direct threat to the very existence of the

relatively large number of Polish transport projects of the period, especially

the costly and politically sensitive water transport network. In the end, the

future of the Augustów Canal was, at least, secured. Meanwhile, only the reactivation

of the Third Council of State in the early 1860s resulted in the proper

reopening of the issue concerning the water transport network in the country

and its adjacent territories. This article will therefore examine the fate of

the Augustów Canal after 1831, with particular emphasis on the struggle for its

preservation shortly after the November Uprising, as well as works concerning

its preservation during the time of transport authorities’ control and official

requests from the Third Council of State for a possible new use for it.

Attention will be also focused on further possibilities of rebuilding the

Windawa Canal and digging the Wisła-Narew Canal and the so-called Brudnów Ditch

(Canal).

2. STRUGGLE FOR THE PRESERVATION OF THE AUGUSTÓW CANAL AFTER THE FALL OF

THE NOVEMBER UPRISING OF 1831

According to the estimated budgets

(“anschags”) for the original construction of the Augustów Canal, the overall

cost of completing this technical project was expected to be 1,152,238 roubles

and five kopecks. As early as the end of 1830, however, when it was obvious

that far more work was needed to complete the entire canal, the sum required for

its construction increased to at least 1,595,598 roubles and 57.5 kopecks[2].

After losing the November Uprising

at the end of December 1831, the Director of the Directorate of Roads and

Bridges of the subdued Kingdom of Poland, Franciszek Christiani, received a

command from the Chief of the Muscovite First Active Army, Field Marshal Ivan

Paskievich, ordering him to make an itinerary for constructing and preserving

works on the Augustów Canal. A further task for Christiani was to establish new

job positions for canal services. Accordingly, on 29 December 1831, Warsaw’s

Government Commission of Internal Affairs and Police stated a report on this

matter, which was then presented on 30 December the same year to the Interim

Government of the Kingdom of Poland. This authority, taking into account that

previously the Augustów Canal had been under the direct supervision of the

(now-defunct) Polish Government Commission of War, decided that, in the

immediate post-uprising period, its management was to be come under the civil

administration of the state (namely, the Government Commission of Internal

Affairs and Police), while reaching the conclusion that the Augustów Canal

itself could no longer be maintained, as originally envisaged, out of the

so-called “separate road funds”.

Against this backdrop, the Polish

Interim Government decided to turn, via its President, Theodor Engel, to Field

Marshal Ivan Paskievich, with questions that concerned the very provisions made

by the Governor as to the further “fate” of this canal. As it was assumed that

Paskevich would decide that management of the Augustów Canal would eventually

pass to Warsaw’s Directorate of Roads and Bridges (the government institution

that would have been responsible in any case for completing the overall construction

of the canal, or at least for providing the financial tools of its

subsistence), members of the Interim Government were especially interested in

what Paskievich had to say about the exact sources of adequate funding for this

canal. At the same time, it was understood that the general oversight of these

funds would be left in the hands of the official financial ministerial

controller of the Government Commission of Internal Affairs and Police, as the

parent body to the Directorate of Roads and Bridges. After the answers were not

provided in full in a timely manner, Governor Paskievich formally decided to

temporarily transfer the management of the Augustów Canal to the

above-mentioned Director of Directorate of Roads and Bridges, Franciszek Christiani[3].

Despite Paskievich’s preliminary

decisions on the Augustów Canal issue, on 27 January 1832, Count Aleksander

Strogonov, Director General of the Government Commission of Internal Affairs

and the Police repeated the overarching question about the financing of works

carried out in relation to this canal. Strogonov further mentioned that, “based

on the explanations given to him privately by Major General Maltzki, under

whose guidance… the Augustów Canal was carried out”, the total amount of costs

for the maintenance and repair of the canal were officially assessed, at this

time, as being 404,000 Polish zlotys, when in fact the actual expenditure would

have been much larger. Hence, the Director of the Commission of Internal

Affairs stated that, in his opinion, there was “even more need to draw the

government’s attention to the utmost necessity to determine the appropriate

funds for the Augustów Canal” in the overall budget for the Kingdom of Poland.

Strogonov noted that, otherwise, one would have to immediately stop any works

on the development and maintenance of this canal, which would entail the utter

destruction of “so costly an enterprise”, or would increase the need to

continue any works related to the canal at some point in the future, which

would occur even more costs than previously expected. In response, the

President of Interim Government, Theodor Engel pointed out that Governor

Paskievich had decided that “the sum needed for this purpose would be placed in

the budget… for the Kingdom”. As such, on 27 January 1832, the Interim

Government ordered the sum of 400,000 zlotys to be included in the 1832 Polish

state budget for further works to be carried out within the next 12 months in

relation to the Augustów Canal[4].

Thus, as we can see, Field Marshal Paskievich took an extremely long time in

deciding to continue such works.

Despite this already considerable

delay, the Polish authorities still had to wait for a final decision from

Paskievich on the most important issue on the possible further financing of the

canal. In this state of relative uncertainty, on 28 February 1832, the Interim

Government, acceding to the request from the Director of the Government

Commission of Internal Affairs and Police, decided to transfer the sum of 5,000

Polish zlotys, from its financial reserve for the general budget of 1832, for

the purpose of “most urgent works around… the channel, to start from the onset

of spring“[5].

On the other hand, on 2 March 1832, Alexander Strogonov (showing once again in

this case his unique determination and stubbornness) requested that Warsaw’s

Interim Government allocate additional funds for the Augustów Canal. As a

result, following a decision by this government, Warsaw’s Commission of Revenue

and Treasury received strict orders to transfer an additional sum of 1,428

Polish zlotys and one grosh for this purpose. Besides, the Interim Government

authorized the Ministry of Revenue and Treasury to create, from within the main

coffers of Augustów Province, the special loan worth 22,546 Polish zlotys and

20 groshes, which were intended for payment during the first four months of

1832 of officials and other workers employed at any of the workplaces along the

Augustów Canal.

Further decisions with regard to

this canal were taken at the end of March 1832 by the revived Administrative

Council of the Kingdom of Poland. Taking into account the inclusion of 400,000

Polish zlotys in the state budget of 1832 to be used on ongoing works related

to the canal, the Council (in addition to a previous decision of the Interim

Government, made on 28 February 1832, and in accordance with the rate

determined by the Government Commission of Revenue and Treasury, dated as of 24

March of the same year) decided that the sum of 5,000 Polish zlotys, which was

intended for temporary canal-related jobs, was to be definitively collected,

not from the so-called state budget reserve fund (as was originally agreed),

but from the fund “of appropriate character”. In this way, the Administrative

Council was able to reduce the fund, which had been originally agreed in the

winter of 1831/1832 for any activity on the Augustów Canal. What was much more

important was the simple fact that this formal decision by the new government

of the Kingdom finally confirmed its will in supporting the final resumption of

the Augustów Canal works, which had been “previously carried out with the

contribution of huge effort and spending a lot of money”[6].

Finally, again under the authority

of the Administrative Council, in 1834, the Bank of Poland took over the entire

process of supervising the implementation of further works on the Augustów

Canal[7].

Fig. 1. Aleksandr Grigorievic

Stroganov[8]

As for important proceedings

regarding the development of the canal during the 1830s, one should admit that

the Government Commission of Internal Affairs, Public Enlightenment Affairs and

Spiritual Matters indicated in its report for 1838 that, after the completion

of the last lock built on the Hańcza River “called Hardwood”, the Augustów

Canal was firstly expected to be completely open as an inland waterway the

following year. Again in 1839, the Ministry of Internal Affairs intended to

submit the so-called channel tariffs for approval by the Administrative

Council. Such fees, levied on ships passing through the canal, were to be used

to repay in the future the sums “borrowed” by the Bank of Poland for the

“completion of that channel”. Additionally, in 1838, Polish administrative

authorities completed the processing of claims submitted by local individuals,

demanding the payment of compensation for their lands occupied by the state for

the construction of the Augustów Canal[9].

In this way, in the period

stretching from December 1831 until the end of 1838, it was possible not only

to save the Augustów Canal from complete closure or partial degradation, for

its construction to almost reach the final stage. It is hard to overestimate

the role of Count Aleksander Strogonov, who was both a Russian General and a

Minister of the Kingdom of Poland at the same time, for his stubborn endeavours

in providing the funds needed for the canal’s further maintenance, especially

in early 1832.

3.

OFFICIAL REPORTS ON AUGUSTÓW CANAL AFTER THE TRANSFER OF THE POLISH WATER

NETWORK TO THE MANAGEMENT OF THE BOARD OF LAND AND WATER COMMUNICATIONS/BOARD

OF

THE 13TH DISTRICT OF COMMUNICATIONS

Despite bold announcements, the

practical process of rafting goods (mostly timber) and floating ships on the

Augustów Canal began not in 1839 but 1840. The final construction costs for

this enterprise, which formally finished in 1844, amounted at the time to a sum

exceeding two million roubles. To this large sum, one obviously needed to add

interest rates, which the State Treasury was obliged to pay back to the Bank of

Poland for the loan granted previously for the purpose of building the canal[10].

In 1844, the management of the

Augustów Canal (with a length of 98 versts) was transferred to the then Board

of Land and Water Communications of the Kingdom of Poland, which was

subsequently known as the Board of the 13th District of Communications from

December 1846. The most important actions undertaken by transport services

dealing with this canal were highlighted as part of periodic reports on the

national administration system, as well as presented in brief on pages of the

officially printed state press. As we discovered from the first report of this

era, issued in 1844, the year the functioning of the Augustów Canal came under

the supervision of the Polish transport authorities was far from successful,

mostly due to floods that took place in August and September of that year,

which generally prevented any repair works from being carried out on the canal

in the expected time frame. Thus, these management activities were postponed to

a later date in 1844, which resulted in the limited capacity of the channel, as

the movement and drifting of items could not be conducted throughout the entire

“navigable period”. Nevertheless, despite these obstacles, all the requiring

repairing works were completed in 1844, which, according to the official

estimated budgets (“anschlags”), amounted to the sum of 5,999 silver roubles

and 13 kopecks[11].

Table 1. Funds allocated for

conservation works on the Augustów Canal, 1845-1852[12]

|

Year |

Allocated funds |

|

1845

1846

1847

1848

1849

1850

1851

1852 |

8,805 silver roubles

13,066 silver roubles

6,130 silver roubles

7,537 silver roubles

8,628 silver roubles 10,815

silver roubles

16,831 silver roubles

4,515 silver roubles |

In 1855, the full cost of ensuring

the proper functioning of the Augustów Canal was estimated at 12,474 silver

roubles. When repairing and proper maintenance of the canal was required in

1856, the Polish transport authorities decided to commission a programme of

repair works totalling 10,325 roubles and 63.5 kopeck. Salaries paid the same

year to canal servicemen were at the level of 4,515 roubles. In 1857, a

programme of works for the proper functioning and maintenance of the canal was

allocated 7,234 roubles and 1.5 kopeck; in following year, this sum needed was

4,568 roubles and 82.5 kopecks. The costs of paying wages to canal workers and

administration staff were at the level of 4,515 roubles in 1857 and the same in

1858.

Supervision over Augustów Canal

inevitably included the proper maintenance of the navigation along parts of the

Biebrza River. The sums spent on maintenance work in this respect were 252 roubles in 1857 and 2,902 roubles in

1858.

It is worth mentioning that, in

1859, the Augustów Canal was fully navigable over a distance of 98,179/500

verstes. To be more precise, the ability to navigate the canal in full lasted

from 3 or 15 April until 1 November, or five- to six-month period. During this

period, maintenance works on the canal were allocated 7,998 roubles and 57

kopecks, while the salary budget for employees of all kinds relating to the

administration of the canal stood at 4,515 roubles. The regulatory Biebrza

River proceedings, considered as part of the canal system, and their control

also entailed expenses of 349 roubles and 11 kopecks[13].

Taking into account the data from

official state reports, generally speaking, funds spent on the functioning of

the Augustów Canal in the period 1855-1859 have been calculated in the amounts

presented in the following table.

Table 2.

Overall funds allocated to the functioning of Augustów Canal transport network

(including maintenance and salary budgets), 1855-1859[14]

|

Year |

Cost of

maintenance, salaries and regulations |

|

1855

1856

1857

1858

1859 |

12,474 silver roubles 14,840 silver roubles & 63.5 kopecks 12,001 silver roubles (including regulatory

works on part of the Biebrza River) 11,985 silver roubles & 82.5 kopecks

(including regulatory works on part of the Biebrza River) 12,862 silver roubles & 57 kopecks

(including regulatory works on part of the Biebrza River) |

Here are two phenomena that are

conspicuous. First, it can be easily observed that, in of 1845, 1848, 1849 and

especially 1852, expenditure on the maintenance of the Augustów Canal was

greatly lowered. Second, one needs to admit that, despite control on the part

of the canal transport network consisting of the Biebrza River being maintained

by St. Petersburg’s Board of Management for Road Communications and Public

Edifices, Warsaw’s transport authorities made (at least in the period

1857-1859) some efforts to regulate

parts of this water flow. These actions, however, were generally limited and

carried out at low cost.

4.

REQUESTS TO INITIATE PROCEEDINGS ON MAKING AUGUSTÓW CANAL MORE ECONOMICALLY

EFFICIENT/(RE)CONSTRUCT AND IMPROVE OTHER CHANNELS

Following the reopening of the

Council of State of the Kingdom of Poland in 1861, requests for improvements to

the technical and administrative functioning of Augustów Canal, as well as

calls to improve the economic benefits of the canal, were received in autumn of

the following year. These proposals were accompanied by an increasing number of

suggestions concerning the construction or reconstruction of other canals, both

within the borders of Kingdom of Poland and located in territories adjacent to

it.

Commencing its research on these matters, the

Department of Tax Administration of the Third Council of State presented a

comprehensive set of accurate data. Moreover, members of the Department

presented in their report a shortened version of the genesis of the Augustów

Canal, writing that the very idea of building a canal was taken

as early as 1824, mostly in order to facilitate trading activities between

Warsaw and the tsarist ports on the Baltic Sea. As was emphasized, the main

goal was, of course, to bypass Prussian customs and undermine the dominant

position of Gdańsk (Danzig) traders, who were seen as incumbents to be held

accountable for restricting local Polish trade. It was then noted that,

originally, the canal was scheduled to join the Narew and Niemen Rivers (this

connection was to have started in the Niemnowo locality near the city of

Grodno, leading to Dembie Village, via the Augustów Canal, where the Biebrza

River would start to flow into Narew watercourse). Out of the Niemen River,

tsarist transport authorities intended to build the so-called Windawa Canal,

leading up to the Latvian Baltic coast, in the Port of Windawa (Ventpils).

Furthermore, referring to the idea of constructing other partially artificial

water transport networks, the Department of Tax Administration also stated that

another water channel was intended to connect Warsaw with the Narew River,

which was planned in the Upper Serock.

Members of the Department of Tax

Administration reminded readers in their short report that, while construction

works on a prospective canal linking the Vistula and Narew Rivers were never

undertaken at any stage, the Windawa Canal was at least partially built.

Nevertheless, this artificial watercourse appeared to be unsuitable for vessels

that typically sailed on the Augustów Canal “because of the smaller size of the

locks [there]”[15].

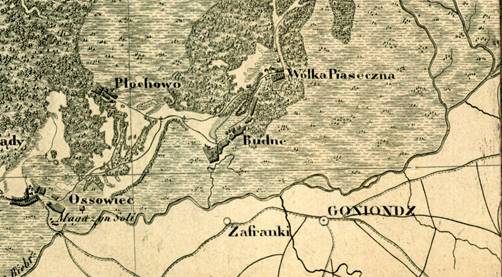

Fig 2. Windawa Canal at its critical

point between the Dubissa

and Wenta Rivers[16]

It was recalled that, under these

circumstances, the Presiding Director of Warsaw’s Government Commission of

Revenue and Treasury, Roman Furhmann, sent an official note to the Chief

Executive of Communications of the Russian Empire (who was, at the same time,

formally in charge of the construction of the Windawa Canal), Adjutant General

Count Karol Fedorowic Toll, asking him “whether the [Windawa] Canal would be

finished, and local of what size/capacity could go on there”. General Toll sent

his response to Furhmann on 4/16 September 1837 in a letter (no. 1,366), in

which he strictly stated that “the width of the channel is applied to the

abundance of water, which had to feed it, and [because of that] it would be

inappropriate to make it wider”. The Chief Executive of Communications of the

Russian Empire also described the then poor conditions of existing parts of the

Windawa Canal, which was ultimately never completed.

Having been reminded about this

short, but decisive, piece of information, members of the Department of Tax

Administration of the Third Council of State emphasized that the Augustów

Canal, originally designed as part of an inner water route linking the Vistula

River to the Baltic Sea, had finally become only an “insignificant internal

communication [tool]”, especially when part of the Biebrza River urgently

needed to be significantly deepened by the start of the 1860s.

The perceived negative impact of the

Augustów Canal on the economy of the Kingdom was strengthened by data

concerning possible profits generated by this canal. These financial results

(showing the true level of the Augustów Canal’s usefulness) were, according to

authors of the Third Council of State proposals of 1862, relatively modest.

Prior to the early 1860s, these profits had reached their highest level,

surprisingly, in 1841, when they amounted to the sum of 2,505 roubles and 31

kopecks[17].

Table 3. Profits generated from the

Augustów Canal

in 1841 and 1859-1861[18]

|

Year |

Sum in roubles & kopecks |

|

1841

1859

1860

1861 |

2,505 roubles & 31 kopecks 283 roubles & 70 kopecks 736 roubles & 75 kopecks 286 roubles & 75 kopecks |

Meanwhile, the maintenance costs of

the Augustów Canal in the draft version of the budget for 1863 included the

following sums – Table 4.

Table 4. Costs of maintenance of

Augustów Canal in 1863[19]

|

Purpose of funds |

Sum in roubles |

|

Canal servicemen/administration |

5,051

4,500 |

|

Total |

9,551 |

Given the existing facts, the

Department of Tax Administration of the Third Council of State acknowledged in

1862 the limited usage and contribution of the Augustów Canal to the national

economy of the Kingdom of Poland, as well as the “adverse results for the

Treasury” resulting from the prevailing need to constantly provide financial

support for its maintenance. It is not surprising, then, that the main cause of

this unfortunate state of affairs occurred in autumn 1862, when attention was

drawn to the incomplete construction of an artificial connection linking the

Vistula and Narew Rivers, via the Windawa Canal, with the Baltic Sea (as well

as the unfortunate construction of this canal’s sluices to standards that did

not completely comply with the demands for vessels floating on the waters of

the Kingdom of Poland).

Accordingly, in 1862, the Department of

Warsaw’s Council of State, in a formal Polish Government statement to Tsar

Alexander II, requested the issuance of an order calling for the Board of Road

Communications and Public Edifices of Russian Empire, together with the Board

of Land and Water Communications of the Kingdom of Poland, to “recognize [and

analyse] the object of the Windawa Canal”. Another Council of State’s

suggestion was to order the Polish Board of Land and Water Communications to

identify any possibilities of building a new canal between the Narew and Vistula

Rivers, as well as deepen the Biebrza River[20].

In their response, members of the Department of Tax Administration expressed,

seemingly, a common belief concerning the improper use of the main water

channel of the Kingdom, as well as demanding the (re)building of the missing

parts of the entire network of canals leading in a north-easterly direction,

including this channel located beyond the borders of the then Polish state.

In his (undated) response, as the

Head of Transport Authorities of the Kingdom, Major General Stanisław Kierbedź,

evaluated in detail all the requests from the Department of Tax Administration

of the Third Council of State dealing with improving the usefulness of the

Augustów Canal and calls for the further construction of other water channels[21].

First of all, Kierbedź referred to the idea of completing the

construction of the Windawa Canal, while reiterating that the failure to do so

had been already repeatedly indicated as the main reasons why only a small

income had been generated by the Augustów Canal itself. He even confirmed that

these financial benefits, in the early 1860s, had reduced even further, mostly

because of salt deliveries destined for state salt warehouses of the Kingdom

being supplied via local watercourses.

Ostensibly, at least, Kierbedź

supported this widespread view held by Polish Government officials, according

to whom it seemed likely that the possible (re)opening of the Windawa Canal

would provide “the opportunity for [Polish] sailing ships to proceed directly to

the Baltic Sea within the boundaries of the Empire”, thereby directly leading

to an expected increase in the number of cargo ships heading in this direction.

Such an idea, of course, suggested that ships sailing on the Augustów Canal

would travel via the Windawa Canal, before flowing directly into Baltic Sea

port at Windawa/Ventspils. The exact water route between the two channels would

lead out of the Niemnowo locality near Grodno, then onto Kowno (Kaunas) and the

Windawa Canal[22].

However, in Kierbedź’s mind, the

Windawa Canal, at the time of writing of his report, “was showing in its image

only a mere shadow of the former works, endeavours and achievements”. To

completely restore, or even to begin any water communication channel via this

route, one would need to start work virtually from scratch. The costs of such

an undertaking would, in the opinion of Stanisław Kierbedź, be extremely high.

The Chief Executive of Land and Water Communications of the Kingdom of Poland

also doubted the usefulness of navigating via this route, pointing to local

navigational difficulties, as the Windawa Canal, at the point in its main water

basin division, had an inadequate number of watercourses to power the (entire)

running of the channel.

In addition to the negative arguments

given above, Kierbedź stressed that ships coming from the Augustów Canal to the

Windawa Canal would have to flow along the Niemen River on its section from

Grodno to Kowno, where some reefs and water thresholds were visible. This had

to be regarded as another major obstacle in the course of canal communication,

whose removal would definitely require further significant financial outlay.

The Major General also acknowledged

that the situation put the emergence of new railways in the region at stake,

such that their construction could be hindered by any further digging of the

Windawa Canal, especially given that any navigation in this direction was far

less necessary than before. Quoting Stanisław Kierbedź, the St. Petersburg

Railway (with its branch line to Konigsberg/Królewiec), which crossed the

Niemen River close to the towns of Grodno and Kowno, would be, in a way,

“replacing water communication on the Niemen River”, while the newly designed

railway to Lipawa/Liepaja “is replacing the Windawa Canal”.

Summing up his arguments in this regard, Major

General Stanisław Kierbedź bluntly stressed that any restoration of the already

built parts of the Windawa Canal to improve operational conditions, as well as

the construction of new sections, would require significant spending by the

Treasury of the Russian Empire “without corresponding and adequate benefits”.

According to the Head of the Government Transport Authority of the Kingdom, any

possible contacts concerning the matter of (re)building the Windawa Canal with

the Board of Road Communications and Public Edifices of the Russian Empire were

completely useless and would not bring about any solutions “which would be

probably expected” by the Department of Tax Administration of the Third Council

of State.

From this perspective and with such

a presumption on the part of Kierbedź, the Augustów Canal was to remain only as

a useful local water-based thoroughfare. Its sound management could bring about

benefits of a new kind, provided there was “proper maintenance and usage of

every drop of water flowing in the canal”, which openly alluded to prior

initiatives of Warsaw’s Board of Land and Water Communications that had also

been supported and confirmed by the Administrative Council. Finally, as the

ultimate counterargument for the resumption of further construction of the

Windawa Canal, the Chief Executive of Transport Services in the Kingdom cited

the previous circumstances in which it was decided to build the Augustów Canal,

which were now fully outdated in a political and economic sense; in other

words, the construction was as a kind of economic response to the raising of

Prussian cereal and transportation fees in early 1820s. Nevertheless, General

Kierbedź did not fail to note the positive impact of the construction of the

Augustów Canal on subsequent lowering of Prussian duties and other charges, as

well as the general failure of the trade war waged by Berlin against the

Kingdom of Poland[23].

The Head of Warsaw’s Transport

Authorities referred, in turn, to the order from the Department of Tax

Administration of the Third Council of State to the Board of Land and Water

Communications to present proposals for deepening the Biebrza River, which was

necessary to the providing a water transport route leading to a basic part of

the Augustów Canal. Acknowledging the comments, Kierbedź described the Biebrza

River as being “a sort of extension of the Augustów Canal, which, up to its

estuary and the Narew River, was managed by two different state organisms”. On

the route stretching from the basic Augustów Canal to Goniądz, the Biebrza

waterway remained under the supervision of the authorities and budget resources

of the Kingdom; from Goniądz to the point where the Biebrza River flowed into

the Narew River near the locality of Wizna, this stretch of water was kept “for

the proper functioning of the watercourse” by the Treasury and officials of the

Russian Empire.

In opinion of the Major General,

appropriate and “easy” rafting on the first of these sections of the Biebrza

River was introduced between 1848 and 1852, after several fascine works had

been completed at a cost of 28,751 roubles. For the sake of proper maintenance

of existing fascine improvements, in 1852, Warsaw’s Board of 13th District of

Communications of the Russian Empire wrote to the Tsarist Governor of the

Kingdom, Field Marshal Ivan Paskievich, a proposal to include (from this moment

forth) in the annual budget of the transport authorities the sum of 1,515

silver roubles and 15 kopecks to be used for this very purpose. In response,

while Paskievich expressed his negative view on the matter, the Field Marshal

allowed the Administrative Council to allocate, by itself, suitable funds for

this sole purpose on an annual basis.

As such, in the period between 1853

and 1861, it was possible to obtain from the Polish Government at least

partially adequate funds for the basic maintenance of fascine works on the

Biebrza River, albeit only on the section from the Augustów Canal to the town

of Goniądz. In reality, during these nine years, the authorities succeeded in

formally allocating the sum of 7,241 silver roubles, which meant that they

acquired significantly less funds than originally expected. Finally, it

transpired that, between 1853 and 1861, even less was spent on repairs to this

section of the Biebrza River, that is, 6,394 silver roubles (statistically

counting 710 roubles and 44 kopecks per year), which was about half of what had

been originally expected. This money had been used entirely for the specified

purpose.

In the opinion given by General Kierbedź in

1862, during the 1860s, rafting continuously took place on the section of the

Biebrza River between the Augustów Canal and Goniądz, especially where there

was at least a depth of 6 ft in the Biebrza watercourse, which was accepted as

suitable for this type of shipping. The temporary lack of any repairs to the

“Polish” section of the Biebrza in 1862 was due to the fact that allocated

funds were needed to cover the salaries of local transport enforcement

officers, at a cost of as much as 216 silver roubles. On the other hand, many

of the other fascine works on the banks of the Biebrza River needed to be

repaired in 1863, mostly because there had been no proper protection for many

years, as costs to address this steadily increased on an annual basis by at

least 5,000 silver roubles.

Much to our surprise, Stanisław

Kierbedź pointed out the evident lack of any precise knowledge on the Board of

Land and Water Communications of the Kingdom of Poland on the matter of the

actual state of the Biebrza River’s current from the town of Goniądz to its

confluence with the Narew River, namely, in its “Russian” section. Such a

ridiculous situation was overtly dealt with by the Head of the Polish Transport

Authorities, who withdrew this section of the Biebrza River from the scope of

Polish responsibility, instead putting it under the strict supervision of the

Board of Road Communications and Public Edifices of the Russian Empire. General

Kierbedź could only note here that “in this section [of the Biebrza], raftsmen

do not complain about any difficulties with their rafting”. This statement was,

however, considered as an obvious admission of the absence of any real

knowledge of any fascine or deepening works possibly undertaken by the Russians

(or rather the Russian invading army) on the stretch of “their” part of the

Biebrza River.

Therefore, based on only partially

accurate data, the Head of the Polish Transport Authorities defended his views,

acknowledging that the Biebrza River did not requiring any serious deepening.

Eventually, Kierbedź chose to focus on maintenance works on the Biebrza

exclusively in relation to the previous repairs along various stretches of the

river, the cost of which would be permanently included in the budget of

Warsaw’s Communication Administration (this was an amount identical to that

proposed back in 1852, i.e., 1,515 silver roubles and 15 kopecks per year [24]).

In his response to several demands

made by the Department of Tax Administration of the Third Council of State, the

Chief Executive of Land and Water Communications of the Kingdom finally

acknowledged the Polish authorities’ proposal to return to the idea of

constructing a completely new canal between the Narew River (starting in the

Zegrze locality) and the capital, Warsaw. Recalling that this project was

originally suggested as far back as 1828, he mentioned that the reason why the

idea had resurfaced all of a sudden in 1857 was due to a new canal initiative

from Adolf Kurtz. This occurred at the same time as when government administrative

authorities became interested in a project to drain a vast expanse of mud lying

near Praga, which was planned to take place in the form of the deepening of the

so-called Brudnów Ditch (in the vicinity of Praga). After several substantive

conferences with transport officials, Kurtz promised to build, within the span

of three years and at his own expense, a wholly “equipped” and fully

functioning sluice channel, located between Praga and Zegrze. In return, Kurtz

formally obtained a government concession to using the watercourse for up to 40

years, along with the permission to have full use of the adjacent waters and

collect fees from people rafting or drifting their products through this

watercourse. General Kierbedź acknowledged that the future opportunities

offered by “this channel, which would link the Vistula River, could be at the

expense of the government”.

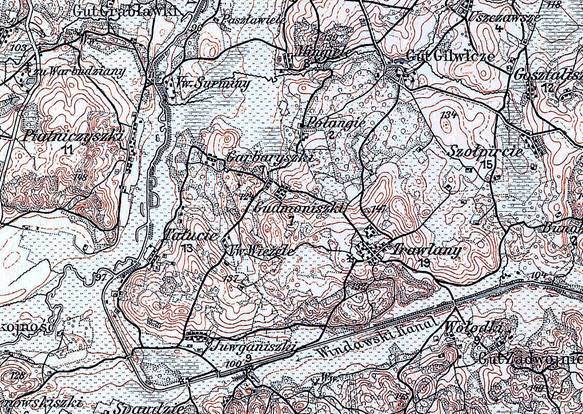

Fig 3. Biebrza River in the vicinity

of Goniądz/division line between Polish and Russian responsibility for this

river[25]

To sum up his position on the idea

of building the Brudnów Canal (Ditch), the Head of Polish Communications

emphasized the synchronicity of Kurtz’s and the Polish Government’s proposals,

as these directly alluded to, or even coincided with, the concept of draining

Praga’s mud fields, which was the project that mostly interested Warsaw’s

Government Commission of Revenue and Treasury. After checking the conditions

and possibilities of local ground levelling, the Commission of Revenue

expressed no objections to the concept presented by Kurtz. Consequently, when

Kierbedź submitted his response to the request from the Department of Tax

Administration of the Third Council of State for the construction of the

Zgierz-Warsaw Canal, Kurtz’s was still being deliberated on and examined in the

offices of the Board of Land and Water Communications, where it was the subject

of a detailed analysis. As such, Stanisław Kierbedź declined to take a literal

position in response to the issues described here[26].

Such a position, moreover, was in harmony with his previous conclusions, in

which Kierbedź not only found a lack of necessity to (re)build the Windawa

Canal, but also saw no need to extensively deepen the Biebrza River.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Derived from the material presented

in this article, it is possible to draw a few interesting conclusions. Firstly,

it seems obvious that, after the initial difficulties in obtaining proper

funding for the ongoing building of the Augustów Canal, which might have

threatened to end, or at least of partially degrade, the project, we can state

that Count Strogonov was someone who, among others, after the fall of the 1831

November Uprising, was strongly supportive of the further existence of this

canal. Secondly, as for the general view concerning the Augustów Canal in the

period of its maintenance by the Polish transport authorities, i.e., since

1844, we can observe that there were extremely low levels of expenditure

allocated for its repairs (especially in 1845, 1848, 1849 and 1852), as well as

the disturbing fact that they always greatly exceeded any profits coming from

its supervision. Thirdly, the activity of the Third Council of State of the

Kingdom of Poland, prior to the January Uprising period (i.e., before 1863),

was characterized by its lively reformist tendency, which could not fail to

grasp the issue of water canal transport management. These problems, indicated

by the Department of Tax Administration of the Council itself, has always been

analysed in respect of the participation of the Kingdom’s transport

authorities, whose postulates referred to further work on a) making the

Augustów Canal more economically efficient, and b) constructing and improving

other channels, including the Windawa Canal and the Wisła-Narew Canal. Finally,

we acknowledge the critical role played by Stanisław Kierbedź, especially in

declining the application for the (re)construction of this watercourse.

References

1.

Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw. The Administrative

Council of the Kingdom of Poland. 1831, 1832. Signature: 20, 21, 22.

2.

Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw. The Administrative

Council of the Kingdom of Poland. 1834, 1838. Signature: 60.

3.

Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw. The Administrative

Council of the Kingdom of Poland. 1862, 1863. Signature: 256.

4.

Fetting Piotr Ivanovic. 2017. Available at: http://dic.academic.ru/dic.nsf/ruwiki/1849081.

5.

Gazeta Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingdom

of Poland]. 1/13 June 1849. No. 128. Warsaw: J. Jaworski.

6.

Gazeta Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingdom

of Poland]. 1/13 June 1850. No. 130. Warsaw: J. Jaworski.

7.

Gazeta Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingdom

of Poland]. 20 September/2 October 1850. No. 220. Warsaw: J. Jaworski.

8.

Gazeta Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingdom

of Poland.] 28 March/9 April 1851. No. 80. Warsaw: J. Jaworski.

9.

Gazeta Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingdom

of Poland]. 16/28 May 1851. No. 118. Warsaw: J. Jaworski.

10.

Gazeta Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingdom

of Poland]. 6th/18th of February 1852. No. 37. Warsaw: J. Jaworski.

11.

Gazeta Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingdom

of Poland]. 4/16 February 1853. No. 35. Warsaw: J. Jaworski.

12.

Gazeta Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingdom

of Poland]. 25 September/7 October 1853. No. 223. Warsaw: J. Jaworski.

13.

Gazeta Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingdom

of Poland]. 7/19 September 1854. No. 205. Warsaw: J. Jaworski.

14.

Gazeta Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego. [In Polish:

Government Gazette of the Kingdom of Poland]. 13/25 January 1856. No. 9.

Warsaw: J. Jaworski.

15.

Gazeta Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego. [In Polish:

Government Gazette of the Kingdom of Poland]. 23 September/5 October 1860. No.

217. Warsaw: J. Jaworski.

16.

Gazeta Rządowa Królestwa Polskiego. [In Polish: Government Gazette of the Kingdom

of Poland]. 7/19 September 1861. No. 208. Warsaw: J. Jaworski.

17.

Karte des Westchlisen Ruslands. M 18. Szawle. [In German: Map of Western Russia].

1892-1921. 2017. Available at: http://www.mapywig.org/m/German_maps/series/100K

_KdWR/ 400dpi/ KdwR_M18_ Szawle_400dpi.jpg.

18.

Mapa Kwatermistrzostwa. CP-43. Augustów. [In Polish: Quarterage Map]. 1850. 2017. Available

at:

http://www.mapywig.org/m/Polish_maps/series/126K_Mapa_KwatermistrzostwaCP-43_Kol_VI_Sek_IV_August%C3%B3w.jpg.

19.

Rutkowski

Marek. 2003. Zmiany Strukturalne w Królestwie Polskim Wczesnej Epoki

Paskiewiczowskiej. Studium Efektywności Administracyjnej, Społecznej i

Gospodarczej Zniewolonego Państwa.

Tom 1. [In Polish: Structural

Changes in the Kingdom of Poland of the Early Paskievic Era. Study of

Administrative, Economic and Sociological Effectiveness of a Subdued Country.

Vol. 1]. Białystok: Publishing House of University of Finances and Management

in Białystok. ISBN: 1732-6613.

20.

Russkaia Imperatorskaia Armia. 92-i Piechotnyj Piecerskij polk. [In Russian: Russian Imperial Army. 92nd Pechersk Infantry Regiment]. 2017.

Available at: http://regiment.ru/reg/II/B/92/1.htm.

21.

Sokolov

Piotr Fedorovic. 1826. Aleksandr Grigorievic Stroganov. 2017. Available

at: https:// pl.pinterest.com/pin/524950900292275893/.

Received 07.01.2017;

accepted in revised form 24.02.2017

![]()

Scientific Journal of Silesian University of

Technology. Series Transport is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License