Article citation information:

Konieczka, R. How to secure basic evidence after an aviation accident. Scientific Journal of Silesian University of

Technology. Series Transport. 2017,

94, 65-74. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2017.94.7.

Robert KONIECZKA[1]

HOW TO SECURE BASIC

EVIDENCE AFTER AN AVIATION ACCIDENT

Summary. This article attempts to provide a synthesis of

basic directions indispensable to accurately collecting evidence after an

aviation accident. The proper collection procedure ensures the avoidance of the

loss of evidence critical for an investigation carried out by law

enforcement agencies and/or the criminal justice system, which includes the

participation of aviation expert investigators. Proper and complete evidence is

also used to define the cause of the accident in the proceedings conducted by

Państwowa Komisja Badania Wypadków Lotniczych (State Committee for Aviation

Incidents Investigation, The State Committee for Aviation Incidents Investigation, hereafter

referred to as the PKBWL). The methodology of securing evidence refers to

the evidence collected at the scene of an accident right after its occurrence,

and also to the evidence collected at other sites. It also includes, within its

scope, additional materials that are essential to furthering the investigation

process, although their collection does not require any urgent action.

Furthermore, the article explains the meaning of particular pieces of evidence

and their possible relevance to the investigation process.

Keywords: aviation accident, evidence, inspection of the

accident scene, personal data records, equipment maintenance and operation

records, flight data recorder

1. INTRODUCTION

The collection of basic evidence is

the key procedural element related to the occurrence of an aviation accident.

Most often, it is performed by representatives of the police or the

prosecutor’s office arriving at the accident scene immediately after the rescue

teams. The collected evidence material, which is used to carry out the

proceedings related to the event, will also be made available to the experts of

the PKBWL in order to determine the turn of events

and the cause of the accident. Hence, the collection of appropriate

basic evidence, both in terms of quantity and quality, seems to be the key

element influencing the quality of proceedings and their effects.

The first and most important task of

all investigation authorities is to properly assess safety. The following

activities should be considered as the most important:

• priority activities related to saving people’s lives

and property in such a manner as to limit the destruction and loss of basic

evidence

• protecting outsiders against the influence of aviation

accident effects

• preventing tampering with basic evidence (wreckage or

its fragments and items that were previously on board the aircraft), including

the protection of somebody else’s property

• limiting access to the accident scene to persons who

are taking part in appropriate activities at the scene

2. ACCIDENT SCENE

INSPECTION

The topic of accident scene

inspection is complex and could alone be the subject of a separate publication.

The issue of inspection must be considered with regard to four areas:

•

inside

the aircraft

•

external

inspection of the aircraft

•

location

of individual elements of the aircraft

•

inspection

of the accident area, locating any trace evidence

Fig. 1. Overview of

an accident scene recorded by aircraft

Accident scene

inspection should include not only the description, but also photos and videos.

Taking photos and videos can be initiated as early as during the rescue action

phase. Later, this could allow for the determination of the scope of rescuers’

intervention after the event. Recording unstable evidence, such as tracks on a

sandy or snowy ground and leakage of working fluids, is of special

significance. It is also important to realize weather conditions (snow, rain,

wind) may result in degradation of basic evidence. Moreover, it is necessary to

prepare a site plan with the location of all identified elements and traces. If

possible, during the inspection, videos from available aircraft or drones may

be used.

During the inspection

of the aircraft interior, all internal spaces should be examined, including

cockpit, passenger

cabin(s), halls, toilets, equipment cabins, hatches, compartments and boots. Of

course, the cockpit is the most important space, whose inspection should

include all its elements, with special consideration paid to:

• indicator visualization

• positions of all control elements

• positions of all switches, valves etc.

• position of the seats, hatches, door, safety belts,

all items regardless of their purpose etc.

In the other cabins, important

elements include:

•

condition

of the cabins and the damages that occurred

•

position

of all indicators, switches, devices and equipment etc.

•

location

and condition of all items present inside

Fig. 2. View of a helicopter

instrument board with recorded positions of indicators and switches

As for the elements of the aircraft, both the

appearance of the elements and their spatial location in the area should be

examined. When there are doubts about the name of a given element, its function

and completeness, members of the PKBWL (if present at the aviation accident

scene) may be asked for help, or the identified element may remain without a

name, but with its appearance recorded.

The final important element of inspection covers all

traces left at the accident scene, which relate to the accident, such as:

• evidence of the aircraft (or its elements) hitting the

ground

• damage to infrastructure (buildings, trees, etc.) in

the area

• evidence of fuel, oil or any other working fluid

leakage

• injuries to non-passengers.

Another important element of the inspection includes

penetration of the area neighbouring the accident scene in order to look for

possible evidence of the aircraft’s interaction or aircraft elements that were

left at a site before the aircraft hit the ground or terrain obstacles. In

particular, this refers to the area located at the flight direction, as

identified in witness statements. As such, the view at the flight direction and

from the flight direction should be recorded.

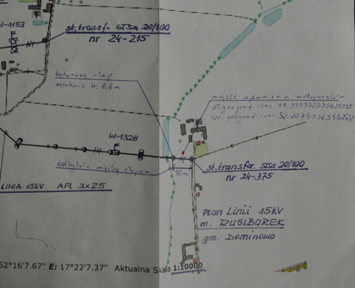

Fig.

3. A fragment of a site plan marking the

place where the aircraft fell down

and the air energy lines (the fall site is described accurately using GPS

position)

3. PROTECTION OF THE

ACCIDENT SCENE

The aircraft wreck should be left untouched until the

inspection. This refers to the aircraft and the detached elements.

Different destructive factors may

occur, depending on the course of the event, its scope and its size. These

factors influence people and are the main cause of different injuries. In

particular, they include the activity of:

•

thermal

factors

•

mechanical

factors

•

pressure

factors

•

chemical

factors

•

electric

current or discharge of electric charge (electrostatic discharge)

•

electromagnetic

radiation

•

radioactive

factors

Upon securing the accident scene, one must take the

following main hazards into consideration:

•

dislocation

of aircraft elements and autonomic activity of mechanic elements

•

occurrence

of fire

•

activity

of fuel and working fluids

•

electric

shock

•

activity

of electromagnetic radiation sources

•

unsealing

of the pressure containers

•

release

of radioactive material

•

explosion

of pyrotechnic agents and armaments

•

activity

of dangerous materials transported on board the aircraft

•

activity

of the infrastructure damaged during the accident

It must be emphasized that only the

appropriate identification of hazards and the expertise of the inspectors allow

for the safe performance of all necessary activities in a manner that is not

dangerous to the health and life of those who perform them.

4. RECORDING

EQUIPMENT

The majority of aircrafts are equipped with a flight

data recorder and/or a voice/radio correspondence recorder in the cockpit. This

especially applies to major communication aircraft (airplanes) and military

aircraft. Recorders, which are usually located in the posterior part of the

aircraft, are mostly rectangular in shape, orange and with an unequivocal

description in English (Flight Data Recorder or Cockpit Voice Recorder).

Further actions taken with respect to the recorders should be carried out by

experts. Until submitted to the experts, the recorders cannot be opened and

dried or removed from the environment in which they were found (e.g., marine

water). Examples of recorders are presented in Figure 4.

Other devices that are

not typical recorders, such as GPS devices, handheld video cameras, mobile

phones, laptops, industrial video cameras and photo cameras, can also provide

information about the flight course.

Fig.

4. Overview of different flight data recorders

5. DOCUMENTATION OF

THE AIRCRAFT AND THE CREW

For a complete evaluation of all the circumstances

related to the aviation event, it is necessary to secure documentation relating

to the crew and the aircraft, as well as documents located on board the

aircraft.

Depending on the aircraft type, the pilot should have

a valid pilot’s licence. With respect to some aircraft, legal provisions

exclude the necessity to have a licence, as they require an appropriate

certificate confirming a pilot’s qualifications instead. This is true for hang

gliders, ultralight trikes, paragliders, parachutes, unmanned aerial vehicles

and ultralight airplanes. In the case of flights performed in an airport area,

a member of the flight crew is not obliged to have the documents with them.

Such a requirement exists, however, when the flight covers landing outside the

airport. In the majority of cases, it is necessary that the pilot (or another

member of flight crew) has confirmation of their pilot medical examinations in

the form of appropriate documentation. This also concerns pilots who are

flying, based on qualification certificates, in the case of training flights or

flights involving passengers. Otherwise, there is no obligation to have a

certificate of pilot medical examinations. A radio operator’s licence is an

additional form of authorization for pilots related to radio communication. In

the case when these documents are not available from the pilot or their flight

organization, the information about current authorizations of flight crew

members and the validity of pilot medical examinations can be obtained from the

respective civil aviation regulatory authority. In the case of foreign

authorizations, their validity in Poland must be verified.

The size of aircraft documentation depends on the

aircraft’s complexity. It always covers two types of documentation:

instructions for use of the given aircraft type and the documentation of the

particular aircraft, confirming its functionality and airworthiness. As for the

first group, such documents include:

•

aircraft flight

manual

•

aircraft technical

manual

•

engine technical

manual

•

rotor technical

manual (if the aircraft has a rotor)

•

aircraft repair

manual

•

any other detailed

manuals of the aircraft or its aggregates

Despite a certain degree of

universality, the documentation should be strictly related to the particular

aircraft, especially with respect to its completeness. Apart from the first

mentioned manual, which should be on board the aircraft, the other manuals should

be stored at the registered office of the aircraft user.

The second group of documents is

documentation directly related to the exploitation of the particular aircraft,

which should contain:

•

aircraft logbook

•

engine log book

•

rotor logbook (if

appropriate)

•

transmission gear

logbook (for helicopters)

•

technical service

programme

•

certificate of

airworthiness (valid on the day of the event)

•

civil liability

insurance policy

•

aggregate

specification

•

bulletins

•

other valid

complementary documentation depending on the aircraft type

As for the already mentioned

aircraft that are partially excluded from the Act of Aviation Law, they do not

require such detailed documentation. Only training aircraft and aircraft used

for passenger flights must have inspection cards (e.g., hang glider or

paraglide) that valid on the day of the event.

Another group of evidence that should be secured at

the accident scene includes all documents located on board the aircraft, such

as maps, airport schemes (instrument approach procedure charts), and any notes

and pieces of handwriting.

6. APPLICABLE

AVIATION ORGANIZATION REGULATIONS

To assess the correct functioning of an aviation

organization, it is necessary to secure all documentation concerning the

organization and the flight training performed. These particularly include:

• operational instructions of an aviation organization

• airport use instructions

• training instructions

• training programmes

With respect to aviation

organizations that need certification from the state aviation authority, it is

legitimate to obtain a certificate. Such certificates define the scope

certified by the supervision authority.

7. WITNESS INTERVIEW

All direct and indirect witnesses to the event must be

immediately identified. This also concerns all persons who could have any

knowledge about the aircraft’s departure site and its service, air traffic,

etc. During these activities, the following witness data must be determined:

full name, address and telephone number, education and profession, and where

the person was located at the time of the accident.

A witness interview should feature the following characteristics:

• it should allow for the free statement of the witness

• the witness’s observation site and locations of the

observed phenomena should be indicated on a map (diagram)

• the witness should be asked for information related to

the position of the aircraft, such as flight track, descending/dropping,

velocity, height, bank, pitch and deviation

• the witness should be asked for information about the

engine function (sounds, fire, smoke, leakage etc.)

• the witness should be asked for information about the

condition of the aircraft, such as angle of control surfaces, landing gear

condition, open hatches, doors, fairings, and detachment of aircraft elements

• the witness should be asked about actions and

behaviour of event participants or other witnesses

• it should refer to other unusual phenomena

• it should determine the applicable weather conditions

in terms of temperature, clouds, visibility, wind direction and velocity, falls

8.

ACTIVITIES RELATED TO AIRCRAFT CREW AND PASSENGERS

All persons who could be responsible for performing

flight-related activities should be immediately identified. At the same time,

the persons should be tested for consumption of alcohol or other agents that

could influence their mode of action. As in the case of the witnesses, basic

information should be collected, as indicated above. Moreover, for members of

the aircraft crew, their function should be determined and documents confirming

they have the qualifications necessary to perform their functions should be

requested, if possible.

In the case of fatalities, among both the crew and the

passengers, it is necessary to perform necropsies in order to determine the

cause of death and any possible influence on their state of health at the time

of the event. The determination of the location and positions of the bodies is

the key element here.

9.

OTHER BASIC EVIDENCE

At the accident site, samples of fuel should be

immediately collected (at least a few litres). The samples should be poured

into at least two completely clean and dry containers. Fuel samples located in

the storage of fuel tanked before the last flight must also be collected. A

laboratory certificate confirming the applicable fuel and any other working

fluids (e.g., oils, hydraulic fluids) should also be secured.

In cases when aviation communication with the aircraft

took place, such communication records should be also secured. These can be

obtained from on-board or ground recorders located in the offices of air

traffic control authorities or airport control centres (e.g., aero club

office). Moreover, recordings from radar devices should be secured if the

flight took place in the area supervised by the radar station. Such recordings

may be obtained at the Polska Agencja Żeglugi Powietrznej (Polish Air

Navigation Service Agency).

Obtaining information about the weather at the date

and location of the accident is also important. Such data can be obtained from

the Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej (Institute of Meteorology and

Water Management), after submitting an official request. The following basic

information must be provided: date, time and place of the accident, including

the height of flight at the moment of the accident. The weather parameters of

interest must also be defined: temperature pressure, strength and direction of

wind, cloudiness type and amount, height of the cloud base, visibility, type

and intensity of precipitation, presence of storms and other phenomena. Data obtained

directly from airports, aero clubs, road regions etc. can also be helpful, as

they are useful when determining any local phenomena, especially in locations

where Instytut Meteorologii i Gospodarki Wodnej (Institute of Meteorology

and Water Management) observation points are not too densely located.

Another significant basic piece of evidence to be

obtained during the later stages of proceedings is an expert opinion, which can

cover various topics, including legal, psychological, psychiatric, medical,

pilot, technical, metallographic, meteorological, fuel, phonetic and other

issues. For simple cases where such narrow specialized expert opinions are not

necessary, the opinion of an aviation expert may be sufficient.

10. SUMMARY

The main areas, as stated above, in

respect of securing evidence after an aviation accident are not exhaustive for

this broad issue. However, they indicate the main directions of activity, as

well as highlight their nature and complexity. In short, this review points to

the sources and methods of basic evidence collection. The activities of the

investigation authorities should also involve initiative and thoroughness,

which require at least a basic knowledge

about the subject matter in order to minimize of evidence loss. Collected and

properly secured evidence is an important basis for starting an investigation.

One must remember, however, that, in many cases, further assessment should be

performed by specialists or experts, since the obtained evidence is often

highly specialized, while incorrect interpretation may result in erroneous

conclusions.

References

1.

Ewertowski

Tomasz. 2015. “Expert investigations at

the aviation accident scene”. Conference

Materials: Catastrophes and Their Explanation in

Process and Criminalistic Terms. Warsaw, Poland, March 2015.

2.

Karsznicki Krzysztof. 2012. “Legal aspects of

aviation accident investigations in the context of a criminal procedure”. Prokuratura i Prawo, Vol. 10.

3.

Klich

Edmund. 1998. Flight Safety. Accidents,

Causes, Prevention. Puławy: Zakład Poligraficzny “Wisła”.

4.

Konieczka Robert. 2015. “Specificity of assessments made by a

court-appointed aviation expert”. Dwunasta

Krajowa Konferencja Biegłych Sądowych. Częstochowa: Stowarzyszenie

Rzeczoznawców Ekonomicznych, April 2015.

5.

Konieczka Robert. 2015. “Possible hazards during investigations at an

aviation accident site”. Problemy

Kryminalistyki, Vol. 289.

6.

Konieczka Robert 2015. “Aviation as a specific field of assessments

made by a court-appointed expert”. Problemy

Kryminalistyki, Vol. 290.

7.

Konert

Anna (ed.). 2013. Legal Aspects of

Aviation Event Investigation in the Light of Regulation T996/2010. Warsaw:

Oficyna Wydawnicza Uczelni Łazarskiego.

8.

Milkiewicz

Antoni (Ed.). 2001. Basis of Organization

and Methods of Investigating Aviation Accidents in Civil Aviation in the

Republic of Poland. Warsaw.

9.

“Act

of 3 July 2002: Aviation Law.” Polish

Journal of Law, 2002, No. 130, Pos. 1112. “Unified text - notice of the

Marshall of the Polish Parliament of 13 September 2013 on publication of a

unified text of the Aviation Law act”. Polish Journal of Law, 28

November 2013, Pos. 1393.

10.

“Regulation

of the Minister of Infrastructure of 18 January 2007 on aviation accidents and

incidents”. Polish Journal of Law,

2003, No. 35, Pos. 225.

11.

Regulation of the European Parliament and EU Council

No. 996/2010 on the Investigation and Prevention of Accidents and Incidents in

Civil Aviation and Waiving Directive No. 94/56/EC.

12.

Investigation

of Aircraft Accidents and Incidents. Attachment 13 to the Convention on

International Civil Aviation (10th Edition). ICAO, 2010.

13. Dąbrowski Tadeusz, Wiktor Olchowik,

Sławomir Augustyn. 2015. “The pilot-helicopter-environment properties in safety

terms”. Diagnostyka, Vol. 16, No. 4:

43-48. ISSN: 1641-6414.

Received 17.11.2016;

accepted in revised form 12.01.2017

![]()

Scientific Journal of Silesian University of

Technology. Series Transport is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License