Article

citation information:

Mindur, M. Economic and transport

aspects of the African Union. Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport. 2018, 100, 143-156. ISSN: 0209-3324. DOI: https://doi.org/10.20858/sjsutst.2018.100.12.

Maciej MINDUR[1]

ECONOMIC

AND TRANSPORT ASPECTS OF THE AFRICAN UNION

Summary. The paper addresses the

changes on one of the largest continents, Africa, in aspect of transport

systems and the economy. The African Union is a chance to integrate this area

from many points of view. Infrastructure, the economic grow rate and transport

development were also analysed.

Keywords: African Union;

transport.

1. INTRODUCTION

Africa is the second-largest

continent in the world, yet the economy of most African countries should be

characterized as underdeveloped. In 2016, the overall GDP of Africa was as low

as 1.5% [24], while the GDP per capita was the lowest among all continents (USD

1,809). Some exceptions to the above rule are the cases of the North and South African

regions, where one can observe diversified production. Despite numerous

challenges, such as terrorism, drought and pandemics, many African countries,

especially those located in the sub-Saharan region, focus on upgrading their

economies by implementing adequate policies intended to stimulate retail trade,

transport, telecommunications and production. Owing to such efforts, the

average GDP growth in the decade 2004-2015 equated to about 5% [7], although

2016 saw an economic slump in Africa, mainly in countries strongly dependent on

the export of minerals and energy-producing raw materials, where the value of

this kind of export was conditioned by prices in global markets. In this day

and age, nearly half of all African countries have already oriented themselves

towards the diversification of national economies [26].

One should also bear in mind that,

even though the African continent is particularly abundant in natural

resources, more than 60% of its population is involved in agriculture (the

share of agriculture in Africa’s GDP is about 32% [10]).

Table 1

Breakdown

of continents according to GDP per capita in 2016 [18]

|

Continent |

GDP

per capita (USD) |

|

North America |

37,477 |

|

Oceania |

35,087 |

|

Europe |

25,851 |

|

South America |

8,520 |

|

Asia |

5,635 |

|

Africa |

1,809 |

|

Global average |

10,300 |

Direct trade between African

countries accounts for as little as 14% of the total trade in goods. It is a

relatively low percentage value compared to the Association of South East Asian

Nations (ASEAN) or the EU, whose intra-regional trade comes to 25% and 60%,

respectively.

In terms of population, Africa is

only outranked by Asia: in 2016, inhabitants of Africa accounted for 16.4% of

the global population (59.8% attributed to Asia) [12].

2. AFRICAN UNION

Despite the economic and

political instability of African countries, most of their leaders strive for

improved dynamism in integration for the sake of a more profound pursuit of the

idea of pan-Africanism. There are numerous

regional organizations currently operating in Africa, also referred to as

regional economic communities, incorporating different countries, with a single

country able to participate in several such organizations. Their collaboration

pertains to the unconstrained transport of goods and people or free trade

zones.

One of the most

important among such international organizations in the past, with nearly all

African countries except for Morocco as members, was the Organization of

African Unity (OAU) established in 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, which ceased

to exist in 2002. It was replaced by the

African Union (AU), which was founded for numerous purposes including

acceleration of the process of economic and political integration of the whole

continent. Its main challenge is to maintain unity and peace in

African countries, and further its principal tasks include fighting poverty and

pursuing major economic improvements on the continent [8]. The AU’s

vision is an “integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven by its

own citizens and representing a dynamic force in the global arena”, while

its main objectives are the following:

· promoting the idea of

democracy and democratic institutions (contrary to the above, believed to be a

club of dictators)

·

intensified protection of human rights on the

African continent

·

implementation of mechanisms of mutual

influence, aimed to put an end to military conflicts and prevent them in the future

·

building and sustaining an all-African outlet

market (by following the global trend of large trade blocs being established)

·

reducing trade with former colonial powers in

favour of intra-continent trade (fighting dependence)

·

increasing the inflow of foreign capital

The AU is composed of

all African countries. It was decided at the AU summit held in 2017 in Addis

Ababa to readmit Morocco to the organization. It used to be the only African country that neither participated in the

OAU, nor in the AU, after it withdrew from the latter in 1984 as a consequence

of the dispute over Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony. Morocco considers

Western Sahara to be its province, while the OAU recognized its independence.

The most important AU

body is the Assembly of the AU, comprising heads of individual governments,

heads of states as well as their representatives. The assembly is convened at

least once a year to decide on the organization’s future endeavours.

Other bodies functioning under the AU are:

· Executive Council -

composed of ministers or authorities appointed by governments of member states

and reporting to the assembly

· Pan-African Parliament

and supporting bodies - intended to ensure empowerment of African peoples as

well as their participation in economic development and integration of the

African continent (a detailed protocol concerning the composition,

prerogatives, functions and organization of the Pan-African Parliament has been

signed by the member states and is currently ratified)

· Economic, Social and

Cultural Council - an advisory body composed of representatives of diverse

social and professional groups from the AU member states

· Court of Justice

· Specialized Technical

Committees (STCs) - operates at the interface with different ministries: i.e.,

STC on Agriculture, Rural Development, Water and Environment; STC on Finance,

Monetary Affairs, Economic Planning and Integration; STC on Trade, Customs and

Immigration; STC on Industry, Science and Technology, Energy, Natural Resources

and Natural Environment; STC on Transport, Communication and Tourism; STC on

Health, Labour and Social Affairs; and STC on Education, Culture and Human

Resources.

The constitution of the

AU stipulates that three financial bodies should be established: the African

Central Bank (commissioned to build a single monetary policy and a single

African currency as the means to accelerate economic integration), the African

Monetary Fund (intended to facilitate economic integration of African economies

by eliminating restrictions in trade and ensuring more improved monetary

integration) and the African Investment Bank (assumed to support economic

growth and accelerate economic integration in Africa).

Systematic and efficient

implementation of the AU’s programmes requires adequate, foreseeable and

regular financing. Each year, the AU member states deposit about 67% of the

estimated contribution. However, there is still a discrepancy between the

budget and the actual financing needs resulting from either incomplete or

non-existent contribution payments by about 30 member states, which makes the

AU’s operations all the more difficult. In 2016, it was decided that all

member states were obliged to contribute 0.2% of their respective import value,

and that the funds thus obtained were to be transferred to the AU budget.

3. CONDITION OF

INFRASTRUCTURE VS. ECONOMIC GROWTH RATE

The transport and power

industries are sectors of key importance to the development of infrastructure

in Africa. In order for them to grow in a relevant manner, they require far

more extensive investments than are observed nowadays. According to the 2016

Africa Infrastructure Development Index (AIDI), a ranking prepared by the

African Development Bank [25], despite the progress observed all over the

continent, the growth rate reported by individual countries was inconsiderable.

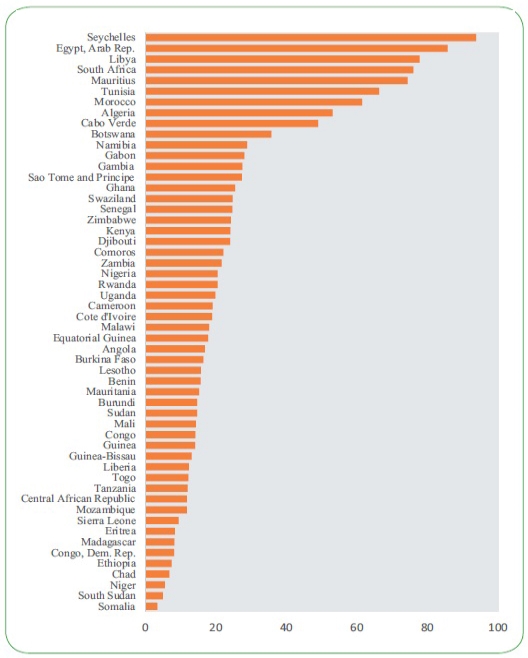

Compared to the 2013

AIDI index, the top 10 ranking highlighting the countries with the most highly

developed infrastructure had not changed. These are the Seychelles, Egypt,

Libya, the Republic of South Africa (RSA), Mauritius, Tunisia, Morocco,

Algeria, the Republic of Cabo Verde and Botswana, although their individual

indicators have changed from time to time. The 10 countries ranked last are:

Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Madagascar, Eritrea, the Democratic Republic of

Congo, Ethiopia, Chad, Niger, South Sudan and Somalia (Figure 1). The most

considerable acceleration was observed in the area of ICT (e.g., owing to the

development of telephony, Mali went up nine places in the ranking, i.e., from

44th in 2013 to 35th in 2016, while Tanzania advanced by two places - from 45th

to 43rd place).

4. DEVELOPMENT OF

TRANSPORT

AU member states are

characterized by relatively low-level transport development; however, the

transport infrastructure has suffered heavy stagnation over recent decades in

Africa. The deficiencies in transport infrastructure hamper the growth and

decentralization of dynamically developing industries, increase transport costs

and reduce the capacity to build a sustainable chain of food supply, thus

generating waste in sellable goods and causing delays in delivery.

The African network of

roads is very poorly developed. The road accessibility index of this continent

is as low as 34% (in other developing regions of the world, it is 50%) [22]. In

many countries, concentration of roads is only typical of urban areas or direct

vicinities of seaports whose trade were routes created in colonial times for

the purposes of goods shipment overseas. Far fewer roads connect adjacent

countries to form regional networks [5]. In this respect, the current status of

the RSA, North Africa, Nigeria and Zimbabwe seems most positive. However, there

are many parts of Africa where 85% of roads are unfit for use during the rainy

season.

Over recent years, road

conditions have improved in most African countries as an outcome of various

policies implemented by governments aimed at increasing the density of roads

and performing institutional reforms. Extraordinary effort has been invested in

the development of institutions dedicated to the management and maintenance of

African roads, yet they are still largely insufficient in many countries [1].

Fig. 1. Status of

infrastructure development in African countries (transport, electricity, ICT,

water supply and sewage disposal systems) [16]

In 1971, the initiative

of the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), supported by the African

Development Bank and the OAU (as the African Union equivalent up to 2002),

launched a project of construction for a network of transcontinental roads

(trans-African highways), also known as trans-African corridors, comprising

nine routes designed to link capital cities and other large urban and

industrial centres (Figure 2).

According to original

assumptions, the network of transcontinental roads was to be 59,100 km long

[27]. However, in 2011, 21% remained undeveloped, while, in midland countries,

this ratio came to 65%. Since 2014, none of the existing transport routes has

had a link through Central Africa. Among the main obstacles to the

construction of the roads were the rain forests and equatorial climate, where

air humidity tends to exceed 90%.

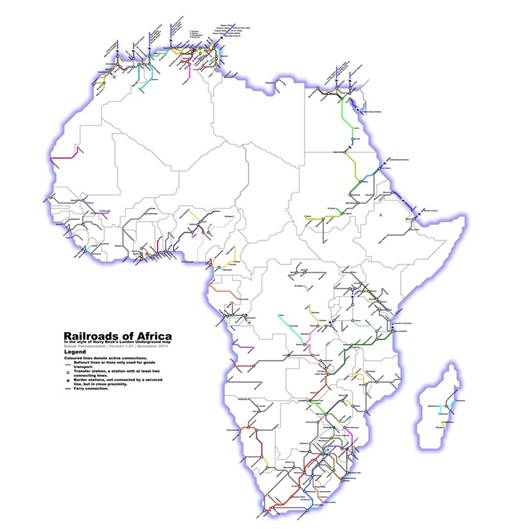

The importance of the

African railway network has dwindled over the last 30 years due to the

liberalization of rail transport in individual countries and the improvement to

road infrastructure. One can actually speak of a properly operating railway

network only with regard to certain contemporary countries of South Africa (RSA

and Zimbabwe), North Africa (Egypt and Morocco) and West Africa (Kenya and

Tanzania). In individual cases, the small traffic volume results from low

demand, while, in others, it is due to rolling stock deficiency, particularly

in terms of locomotives. The predominant type of railway is the narrow-gauge

system (1,067 mm) with low permissible axle loads.

As railway traffic has

dropped in volume, very few carriers can generate revenues high enough to cover

the necessary investments. Revamping the ageing railway networks and adequately

restoring their technical condition would require a one-time injection of funds

equal to USD 3 billion. In 1993, several governments started granting

concessions for the use of railway lines, which was directly linked with a

revitalization programme financed by international institutions. However,

insofar as the concessions have led to significant improvements in the quality

of services and helped to reverse the trend of traffic volume decline, they

have not generated high enough revenues to cover the railway network upgrading,

that is so desperately needed. The only railway lines truly meaningful to the

African economy are those used to transport minerals from mines to seaports

[2].

More than 90% of imports

to and exports from the AU is handled by sea. In terms of sea transport, the

RSA plays the most crucial part. Since the mid-1990s, both bulk and container

cargo transferred through African ports have grown threefold in terms of

volume. However, further growth will require additional investments, since the

capacity of these ports still remains considerably below international

standards. Although a decisive majority of ports have been deregulated, many AU

countries have maintained high tariffs for harbour charges [3].

The busiest and largest

African ports are: Durban in the RSA (the largest container terminal receiving

about 4,500 vessels a year with total turnover exceeding USD 45 billion),

Mombasa in Kenya (providing connections with about 80 ports all over the world,

where about 500,000 TEU are handled per annum), Djibouti (connecting East Africa

with Europe and Asia), Lagos in Nigeria, Abidjan in the Republic of Côte

d’Ivoire (with an annual throughput of 610,000 TEU), the 163-m long Suez

Canal in Egypt (total tonnage in 2014 came to 962.7 million tonnes, with

revenues of USD 5.45 billion) and Tangier, Morocco [20]. The largest container

terminals handling general cargo shipments are compared in Table 2.

The multitude of

projects aimed at facilitating the development of African ports may imply some

positive prospects concerning the region’s increasing production

capacity, but the hampering factor is the considerable uncertainty of economic

growth.

Air transport has

significantly developed over recent years in the AU, yet, even in this sector,

one may observe large disproportions between individual regions. Availability

of air transport services has particularly contributed to the growth of

exports. However, air transport is expensive and connections are irregular in

Africa, while safety is an additional issue due to such problems as low

standards of pilot training and air traffic control and supervision. In many

countries, air connections have been significantly limited in numbers on

account of the abruptly growing operating costs related to increasing prices of

fuels. The political efforts undertaken by national governments include the

tightening of regulatory oversight and pursuing full liberalization of the air

transport sector [4].

Fig. 2. Trans-African

road transport corridors [17]

The largest African airports are: Oliver Tambo in Johannesburg (RSA),

Cairo International Airport (Egypt), Cape Town International Airport (RSA),

King Shaka International Airport near Durban (RSA), Sharm El Sheikh

International Airport (Egypt), Hurghada International Airport (Egypt),

Casablanca Mohammed V International Airport (Morocco), Murtala Muhammed in

Lagos (Nigeria), Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi (Kenya) and

Port Elizabeth International Airport (RSA).

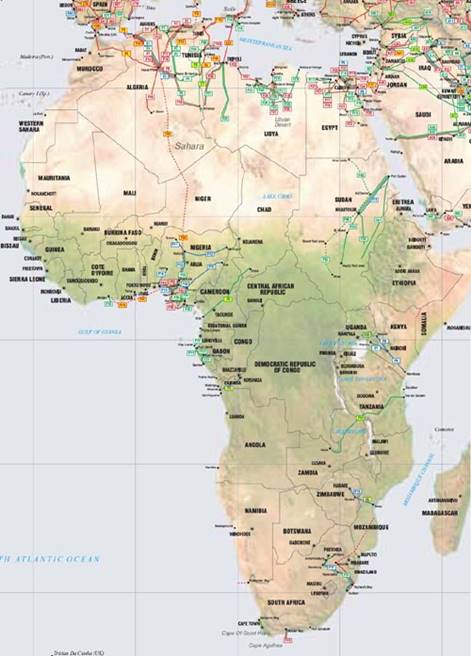

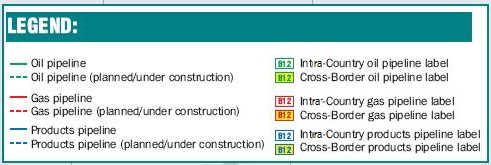

Africa holds its largest

petroleum deposits in the northern and south-western part of the continent,

while it is most abundant in natural gas in North Africa. Both kinds of fuel

are transported to maritime trans-shipment hubs by pipelines (Figure 4).

Most pipelines cut

through Algeria (27,042 km), Egypt (15,088 km), Nigeria (12,590 km) and Libya

(10,748 km) [13].

Fig. 3. Railway system

in Africa [23]

Algeria is the largest

natural gas producer in Africa. The mid-1980s saw the commissioning of an

important partially undersea gas pipeline leading from the Algerian deposits in

Sahara, through Tunisia, the Strait of Sicily and the Strait of Messina to

Italy. Another connection between Africa and Italy is the Greenstream pipeline

supplying gas from Libya. This fuel is also transferred by two pipelines to

Spain, one which cuts through Moroccan territory and the other laid on the

bottom of the Mediterranean Sea

The extraction and sale

of power-producing raw materials contribute to the good economic results

attained by the AU countries. The development of East Africa has been boosted

over recent years by the discovery of rich deposits of petroleum in Uganda and

Kenya as well as equally extensive deposits of natural gas in Tanzania. Ghana

has also already attempted the construction of infrastructure required to

utilize the natural gas deposits at hand, while it plans to increase the rate

of its economic growth by consistent implementation of fully integrated and

cost-effective operations of the gas industry [14].

Table 2

Largest

container terminals handling general cargo shipments in the AU

|

Port name |

Country |

Location |

Annual

transfer capacity |

Characteristics |

|

Durban Container Terminal |

RSA |

Durban Port |

3.6

million TEU (target capacity: 4 million TEU) |

- Currently under

expansion works aimed at dredging to 16 m -

Only African terminal with container cranes capable of lifting 80-tonne

loads, which enable servicing of ships with 24 containers on board |

|

Suez Canal Container Terminal |

Egypt |

Port Said - northern entrance to the Suez Canal |

About 2.8 million TEU (target capacity: 5 million

TEU) |

-

Currently under expansion to enable handling of the largest container ships:

dredging to 16.5 m, installation of 23 Post-Panamax container cranes |

|

Tangier Med |

Morocco |

Tangier Port |

2.5 million TEU |

-

State-of-the-art container cranes -

Dredged fairway |

|

Alexandria International Container Terminals |

Egypt |

Alexandria Port |

1.5 million TEU |

-

Facility comprising two terminals: in Alexandria and in El-Dekheila |

|

Cape Town Terminal |

RSA |

Cape Town |

900,000 TEU (target

capacity: 1.6 million TEU) |

Equipped

with special cooling containers for transportation of frozen fruit and other

products |

Fig. 4. Pipelines in Africa [19]

Table 3

Length of

pipelines in African countries in 2013 in km

|

Country |

Gas pipelines |

LPG

pipelines |

Petroleum pipelines |

Pipelines

for transport of petroleum refining products |

Total |

|

North Africa |

|||||

|

Algeria |

16,415 |

3,447 |

7,036 |

144 |

27,042 |

|

Egypt |

7,986 |

957 |

5,250 |

895 |

15,088 |

|

Libya |

3,743 |

|

7,005 |

|

10,748 |

|

Sudan |

156 |

|

4,070 |

1,613 |

5,893 |

|

Tunisia |

3111 |

|

1,381 |

453 |

4,945 |

|

Cross-border pipelines: Algeria-Italy

(2,592 km), Algeria-Morocco, Algeria-Spain (200 km), Algeria-Tunisia (775

km), Egypt-Jordan (260 km), Libya-Italy (516 km), Libya-Tunisia (260 km),

Morocco-Spain (257 km), Nigeria-Algeria (4,400 km) |

|||||

|

West Africa |

|||||

|

Côte

d’Ivoire |

256 |

|

118 |

|

374 |

|

Gabon |

807 |

|

1,639 |

|

2,446 |

|

Angola |

352 |

85 |

1,065 |

|

1,502 |

|

Democratic Republic of

Congo |

62 |

|

77 |

756 |

895 |

|

Chad |

|

|

582 |

|

582 |

|

Cameroon |

53 |

5 |

1,107 |

|

1,160 |

|

Ghana |

394 |

|

20 |

361 |

775 |

|

Nigeria |

4,045 |

164 |

4,441 |

3,940 |

12,590 |

|

Cross-border

pipelines: Angola-Democratic

Republic of Congo, Chad-Cameroon (1,045 km), Ghana-Côte d’Ivoire,

Nigeria-Ghana (1,033 km) |

|||||

|

East Africa |

|||||

|

Kenya |

|

|

4 |

928 |

932 |

|

Uganda |

|

|

|

No data |

No data |

|

Tanzania |

311 |

|

891 |

8 |

1,210 |

|

Zambia |

|

|

771 |

|

771 |

|

Cross-border

pipelines: Kenya-Uganda (320 km), Tanzania-Zambia |

|||||

|

South Africa |

|||||

|

RSA |

1,293 |

|

992 |

1,460 |

3,745 |

|

Mozambique |

972 |

|

|

278 |

1,250 |

|

Zimbabwe |

|

|

|

270 |

270 |

|

Cross-border

pipelines: Mozambique-Zimbabwe |

|||||

5. DEVELOPMENT

PERSPECTIVES

All AU member countries

have fully recognized the importance of sustainable infrastructure for economic

and social growth; therefore, individual national governments actively strive

for the appropriate coordination of state interventionism, which contributes to

the improvement of internal trade and boosts economic results in trade

worldwide.

In 2010, the AU launched

a common initiative referred to as the Programme for Infrastructure Development

in Africa (PIDA), intended to support the development and implementation of

investment schemes in the areas of regional and continental infrastructure

(energy, transport, ICT as well as cross-border water resources) from a short-,

medium- and long-term perspective until 2020 [6]. The programme was approved in

2012, while the institution appointed to implement it is the African

Development Bank Group.

Numerous road and

railway construction projects are currently being delivered across the AU under

the PIDA scheme. An example of such endeavours is the construction of more than

9,400 km of motorway connecting Algiers and Lagos (Nigeria), also known as the

Trans-Sahara Motorway. The transport corridor cutting through the desert, the

completion of which is scheduled for 2018, will facilitate trade between North

Africa and sub-Saharan Africa by linking Algeria, Tunisia, Mali, Niger, Chad

and Nigeria [9].

Another transport

project planned for implementation in East Africa is the Lamu Port-South

Sudan-Ethiopia (LAPSSET) corridor, including standard railway and road

connections between the largest Kenyan port of Lamu and Ethiopia and South

Sudan. It also covers construction of a pipeline for the transport of petroleum

and petroleum derivatives, the construction of a refining plant and the

expansion of the Kenyan airports of Lamu, Isiolo and Lokichogio [21]. The RSA

has also joined the project and, by building a road from Johannesburg, strives

for a prospective connection with Cairo.

Assuming that all the

projects planned will be successfully completed, it is highly probable that the

AU’s economic growth will rocket upwards. For instance, one can observe

a sudden growth in the number of projects implemented in West Africa,

these being mainly driven by Chinese investments in infrastructure. Expansion

of the second-largest port in Ghana, Tema, is scheduled for completion by the

end of 2019, with the project comprising the construction of a new deep-water port

capable of servicing ships of the latest generations (up to 18,000 TEU). The

investment to be completed under the public-private partnership format, with

the participation of Meridian Port Services, a joint venture company

incorporating Bolloré Transport & Logistics, APM Terminals and the

government of Ghana operating via the Ghana Ports and Harbours Authority, is

expected to consume USD 1.5 billion [11]. Yet another Ghanaian port, Takoradi,

is currently being modernized. The investment of USD 197 million is co-financed

by the governments of Ghana and China, while the implementation itself is

supervised by Chinese engineering companies [15].

There are also numerous

uncertain projects, hindered by the general economic and political situation,

as well as the obstacles to container trade. Although some of them will

probably be completed, others may require further foreign capital support,

especially from carriers expected to invest in the railway infrastructure.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The deficiency in

infrastructure in Africa is a widely recognized problem. Member states of the

AU are among the least competitive countries in the world, while their

infrastructure seems to be one of the most significant factors that hamper

their economic and social development. The latter issue, however, applies to

the entire AU and thus requires a pan-continental solution.

There are many small

African countries with populations below 20 million and budgets of less than

USD 10 billion. Their infrastructural systems, similarly to their borders, are

reflections of the continent’s colonial past, while their roads, ports

and railways were built for raw material extraction purposes and as means of

political control, rather than for the sake of economic and social

consolidation of different territories. Regionally shared infrastructure seems

to be the only efficient solution to the problems of small size and

unfavourable location. The positive valued added by African regional

infrastructure is in its effect on trade, while the common goal, in terms of

stimulating economic growth, is to develop the technologically advanced

transport corridors.

Therefore, whether or

not Africa will maintain the current growth trend depends, to a large extent,

on how quickly it will be able to move from its dependence on traditional

commodity markets towards a modern economy based on technological development.

Such is the task set by African countries for themselves and the rationale

behind the establishment of the AU.

References

1.

“Africa

Infrastructure Knowledge Program”. Available at:

http://infrastructureafrica.opendataforafrica.org/zdigrbg/roads.

2.

“Africa

Infrastructure Knowledge Program”. Available at:

http://infrastructureafrica.opendataforafrica.org/bgerkj/railways.

3.

“Africa

Infrastructure Knowledge Program”. Available at:

http://infrastructureafrica.opendataforafrica.org/rmvcwwd/ports.

4.

“Africa

Infrastructure Knowledge Program”. Available at:

http://infrastructureafrica.opendataforafrica.org/zlspaoe/air-transport.

5.

Africa

Renewal. “Building an efficient road network”. Available at:

http://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/september-2002/building-efficient-road-network.

6.

“African

Development Bank Group”. Available at:

https://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/initiatives-partnerships/programme-for-infrastructure-development-in-africa-pida/.

7.

African Development Bank. 2017. African Economic Outlook 2017.

8.

“African

Union”. Available at: https://au.int/en/history/oau-and-au.

9.

“All

Africa”. Available at: http://allafrica.com/stories/201504281269.html.

10. Davies M. 2016. “Africa’s

economic prospects in 2016: looking for silver linings”. BBC News. Available at:

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-35261906.

11. “Bollore Transport &

Logistics”. Available at:

http://www.bollore-transport-logistics.com/en/media/news/port-of-tema-a-giant-is-born.html.

12. “Central Statistical Office

(GUS)”. Available at:

http://stat.gov.pl/statystyka-miedzynarodowa/porownania-miedzynarodowe/komentarze-analityczne/.

13. “CIA World Factbook 2017”.

Available at: https://www.theodora.com/pipelines/africa_oil_gas_and_products_pipelines_map.html.

14. “Ghana National Gas Company”.

Available at: http://ghanagas.com.gh/about-us/our-business/.

15. “GIPIC Ghana Investment Promotion

Centre”. Available at:

http://www.gipcghana.com/invest-in-ghana/why-ghana/infrastructure/harbours-infrastructure.html.

16. “Africa Infrastructure Knowledge

Program”. Available at:

http://infrastructureafrica.opendataforafrica.org/

17. Available at: http://www.ethionation.com/sites/news/18982-arab-contractors-will-participate-in-ethiopian-road-project.html.

18. “the continents of the world per

capita GDP”. Available at: http://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-continents-of-the-world-by-gdp-per-capita.html.

19. “Seplat”. Available at:

https://seplatpetroleum.com/about-us/market-overview/.

20. “Africa‘s busiest and largest

ports”. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/africas-busiest-largest-ports-ralph-dinko.

21. “Kenya Ports Authority”.

Available at: https://www.kpa.co.ke/OurBusiness/pages/lamu.aspx.

22. “Programme for Infrastructure

Development in Africa (PIDA) (2015)”. Available at:

https://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/initiatives-partnerships/programme-for-infrastructure-development-in-africa-pida/.

23. African Development Bank. 2015. Rail Infrastructure in Africa. Financing

Policy Options.

24.

Regional Economic Outlook, World Economic

and Financial Surveys 2016.

25. The Africa Infrastructure. 2016. Development Index 2016. AfDB. Chief

Economist Complex.

26. Atlantic Council. 2016.

“Understanding Africa’s disappointing economic growth in

2016”. Available at:

http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/understanding-africa-s-disappointing-economic-growth-in-2016.

27. UNECA

Report: Review of the Implementation Status of the Trans African Highways and

the Missing Links. Volume 1: Main Report.

28. Bakowski H. J. Piwnik. 2016.

“Quantitative and qualitative comparison of tribological properties of

railway rails with and without heat treatment”. Archives of Metallurgy and Materials 61(2): 469-474. DOI:

10.1515/amm-2016-0037.

29. Tolmay A.S. 2017. “The correlation between

relationship value and business expansion in the South African automotive

supply chains”. Journal of

Transport and Supply Chain Management 11(a245). DOI: https://doi.org/10.4102/jtscm.v11i0.245.

30. Dzuke A, Naude M.J.A. 2017.

“Problems affecting the operational procurement process: a study of the

Zimbabwean public sector”. Journal

of Transport and Supply Chain Management 11(a255). DOI:

https://doi.org/10.4102/jtscm.v11i0.255.

Received 03.04.2018; accepted in revised form 30.08.2018

![]()

Scientific

Journal of Silesian University of Technology. Series Transport is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License